The Shakty Case

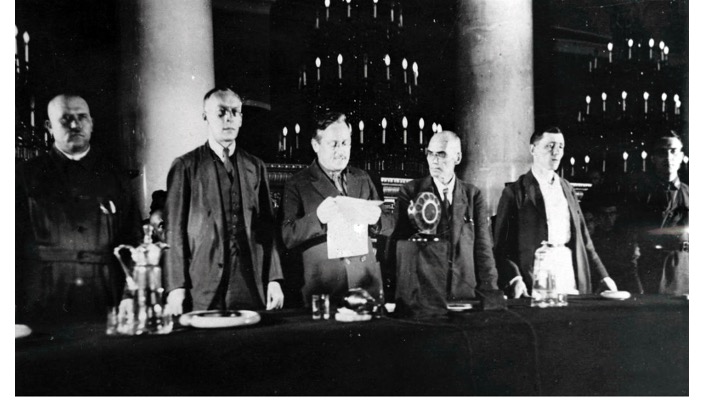

Picture shows Vyshinsky reading the verdict at the Shakhty Trial; from Wikimedia Commons

September 13, 2025 MLRG.online

This article from circa 2000, written by W.B.Bland, is being republished, as it is cited in a shortly forthcoming new article. It is relevant to the role of bourgeois experts in the USSR of 1927-1931. The Marxist-Leninist Research Bureau in London was based in his home.

Editors, MLRG.online

THE MARXIST LENINIST RESEARCH BUREAU Report No. 5 THE SHAKHTY CASE

Previously published on internet for Marxism-Leninism Currents Today, 2021 at www.ml-today.com; then at Bill Bland Internet Archive www.marxists.org (uploaded 2021); republished at MLRG.online September 13, 2025

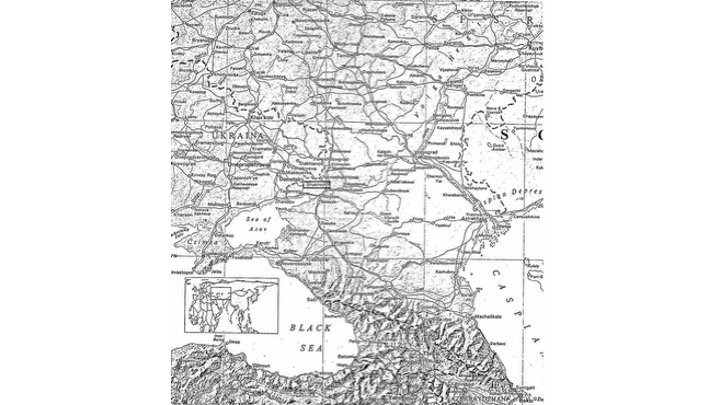

The city of Shakhty (formerly Caucasus, in the Rostov-on-Don Soviet Republic (RSFSR).

Aleksandrovsk-Grushevsky lies in the North district of the Russian Socialist Federal

In late 1927, Yefim Yevdokimov, the representative of the Unified State Political Directorate (OGPU) in the North Caucasus, presented to Vyacheslav Menzhinsky*, the Chairman of the OGPU board:

“a detailed secret report making it plain that there was an illegal counter-revolutionary sabotage group in the city of Shakhty in the North Caucasus. Its members were said to be old-time engineers. The report presented evidence tending to prove that the persons concerned were in touch with the former owners of the Shakhty mines, now living abroad, and that they planned. to wreck the mines by systematic sabotage. The Lubyanka (Lubyanka: the headquarters of the USSR Ministry of the Interior) headquarters was very sceptical”.

Abduraklunan Avtorkhanov: ‘Stalin and the Soviet Communist Party: A Study in the Technology of Power; London; 1959; p. 28

Yevdokimov

“went to Stalin, to whom he reported the entire matter…

Said Stalin: ‘Go back to the North Caucasus and immediately adopt whatever measures you consider necessary. From now on send all your information to me only, and we will take care of Comrade Menzhinsky ourselves’. (Stalin represented the Party Central Committee on the OGPU board). Having thus been given carte blanche, Yevdokimov dashed off to Rostov, the capital of the district in which Shakhty was located. Two days later, the leading engineers in Shakhty were arrested”.

Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov: op. cit.; p. 29

Stalin,

“the Party’s General Secretary, assumed direct supervision of the (Shakhty — Ed,) case.”

Kendall E. Bailes: ‘Technology and Society under Lenin and. Stalin: Origins of the Soviet Technical Intelligentsia: 1917-1941; Princeton (USA); 1978; p. 75

and at the 16th Party Congress in 1930, Lazar Kaganovich*

“praised. Stalin’s foresight in pursuing the prosecution of this (Shakhty -· Ed.) case, against Rykov’s* opposition to it in the Politburo”.

Kendall E. Bailes: op. cit.i p. 74

Proceedings were

” … initiated by organs of the Unified State Political Directorate (OGPU) in early 1928″.

‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 29; New York; 1982; p. 529

against

“53 defendants, primarily engineers and technicians”.

‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 29; ibid.; p. 529

The Trial (1928)

Between 18 May and 6 July 1928, the trial of the accused in the case took place before a special session of the USSR Supreme Court public held in Moscow:

“in the Hall of Columns of Moscow’s House of Unions … with foreign correspondents present”.

Robert C. Tucker: ‘Stalin in Power: The Revolution from above: 1928-1941’; New York; 1990; p. 76

The presiding judge was Andrey Vyshinsky*, and the prosecutor Nikolay Krylenko*.

“The accused were a group of fifty-three engineers, including three German citizens…

Most were representatives of the old technical intelligentsia employed as ‘technical directors’ under Soviet managers who were generally Party men with little technical knowledge.”

Robert C. Tucker: op. cit.; p. 76,

The accused

“were charged with participating in a foreign-based criminal conspiracy to wreck the Soviet coal-mining industry and put the Donbas out of action by deliberate mismanagement of operations. The conspirators were said to have acted on behalf of the Polish, German, and French intelligence services, as well as the former mine and factory owners now living in emigration.”

Robert C. Tucker: op. cit.; p. 76

”The long Act of Accusation … described an organised network of espionage and sabotage with centres in Moscow and Kharkov, Warsaw, Berlin and Paris; emissaries carrying instructions and money from expropriated mine owners abroad to Russian engineers in the Donetz Basin coal area where Shakhty was located; technicians, spoiling machinery, undermining the revolution’s fuel supplies, inveigling the Soviet government into waste.fol expenditures; preparations to destroy the coal industry as soon as war or intervention started; German firms palming off defective machinery with the connivance of bribed engineers.

Here was international plotting on the grand scale”. (Eugene Lyons.: ‘Assignment in Utopia’; London; 1938; p. 117).

A number of the defendants made full or partial admissions of guilt:

“Ten of the fifty-three defendants made full confessions and implicated the others; another half-dozen made partial confessions. (Rober C. Tucker: op. cit.; p. 77-78),

and several denied in court that pressure had been brought to bear on them to confess:

”Did anyone force him to confess, Krylenko wanted to know (from the defendant Skorutto – Ed.)..

Skorutto… wrung his hands and wandered about the platform. No. Nobody had forced him, he finally said”.

Eugene Lyons: op. cit.; p. 125

“Krylenko gazed at him and finally said quietly: ‘Do you want to say that you were intimidated, threatened?

Benbenko hesitated and then said ‘N”.”

Robert Conquest: ‘The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties’; London; 1973; p. 731.

According to Eugene Lyons*, the Russian-born American journalist who attended the trial, the defendants presented

II …

“… a sorry picture. Only by a violent stretch of the imagination could one cast these grovelling men in heroic roles, either as martyrs or as great conspirators. Guilty or innocent, they were men defeated, impotent, without a deep faith or hope for the future to sustain them. Not one of them had advanced any more exalted motive for spoiling machines or opposing the revolution than his own desire for more wealth. The group as a whole seemed to me a sad exhibition of what the age-old system of private greed does to its most devoted servants.”

Eugene Lyons: op. cit.; p. 130, 131

On 6 July 1928, 49 of the 53 defendants were found guilty, while

“four were acquitted.”

(‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 29; op. cit.; p. 530

“The Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced five persons to be shot; 40 persons were sentenced to imprisonment for one to ten years. Four others received suspended sentences.”

‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 29; ibid.; p. 530

Despite his anti-Soviet views, Lyons was certain of the guilt of most, if not all, of the accused;

“I felt certain. of only these things:

First, that most, if not all, of the accused men were guilty either of actual sabotage against the Soviet regime, or of such utter apathy toward their work that the results amounted to sabotage”’.

Eugene Lyons: op. cit.; p. 132

Many Soviet Communists considered the sentences too lenient:

“The opinion was widespread in Party circles that the sentences had been too light11

Edward H. Carr & Robert W. Davies: ‘Foundations of a Planned Economy: 1926-1929’; Volume 1; London 1969; p..585

Presumption of Innocence in Soviet Criminal Law

Some commentators criticise Soviet criminal law on the alleged grounds that it did not recognise the principle of presumption of innocence of an

accused person.

This allegation is untrue.

“It is presupposed by the entire system of Soviet criminal procedure that the burden of proof of the guilt of the accused person rests on the prosecutor and that the accused is not required to prove his innocence. Indeed, in contrast with the usual rule in American courts, even the admission of his guilt by the accused did not necessarily dispense with the requirement of a trial.”

Harold J. Berinan (Ed..): ‘Soviet Criminal Law and Procedure: The RSFSR Codes’ ;. Cambridge (USA); 1966; p. 80).

In 1946, the Plenum of the USSR Supreme Court:

“in reversing a conviction, stated that the lower court’s decision violated the basic principles of Soviet criminal law, according to which any accused person is considered innocent so long, as his guilt is not proven.”

Harold J. Berman (Ed.): op. cit.; p. 86-87

“Soviet legislation links the right to defence indissolubly with the presumption 10£ innocence, in accordance with which the accused is considered innocent… until his guilt has been proved by due process of law.

Until guilt has been proved, the accused is considered innocent”.

Yuri Stetsovsky ‘The Right of the Accused to Defence in the USSR’; Moscow; 1992; p. 34, 38).

“It is precisely the presumption of innocence that prohibited identifying the accused with the convict.. Before a person’s guilt is shown and established by a judgment of a court, such a presumption does not allow a person to be considered guilty merely because criminal proceedings have been instituted against him”.

Mikhail S. Strogovich: ‘Kurs sovetskogo ugolovnogo protcessa’ (Course of Soviet Criminal Procedure) ; Moscow; 1968-70; p. 149

Revisionist Assessment of the Shakhty Case

Opposition leaders at this time did not question the justice of the verdicts at the Shakhty trial:

“It was irrefutably established by the Court that during the years 1923-8 the bourgeois specialists, in close alliance with the foreign centres of the bourgeoisie, successfully carried through an artificial slowdown of industrialisation, counting upon the re-establishment of capitalist relationships.”

Leon Trotsky; ‘Problems of the Development of the USSR’ (April 1931). in: ”Writings of Leon Trotsky (1930-31)’ ; New York; 1973;

“Bukharin*, Rykov and Tomsky* … did not question the facts of the Shakhty affair”.

Stephen F. Cohen: ‘Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography: 1888-19381; London; 1974; p. 281)

As late as 1982, the official ‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, published by the revisionists, expressed no doubts about the justice of the verdicts in the Shakhty case:

“The (Shahkty – Ed.) trial demonstrated that among the old specialists employed by the coal industry were persons associated with the former owners of the mines. The Shakhtintsy, as these persons were called, were guilty of subversive activities for which they received,ed remuneration from the former bosses, who had fled abroad,

When the New Economic Policy had been introduced, the former mine owners had assigned their agents the task of regaining what they called ‘their’ enterprises through denationalisation or concessions. As the socialist structure of the economy grew stronger, however, these hopes were dashed; the former owners then became the instigators of an active, organised wrecking campaign.

The activities of the Shakhtintsy were directed by the Former Mining Industrialists of Southern Russia J which was headed by B. N. Sokolov in Paris, and the Polish Association of Former Directors and Owners of Mining Enterprises in the Donetz Basin, which was headed by Dworzanczyk. These associations were linked with the governments and intelligence services of capitalist countries, and they established wrecking groups in the Donbas, Kharkov ( 1923-24) and Moscow (1926). The Shakhtinsky sought to weaken the defences and economic strength of the USSR and to create favourable conditions for intervention by the imperialist states. Their acts of sabotage included dynamiting and flooding mines and setting fire to power plants.”

‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 29; op. cit.; p. 529-30

Dissident Revisionist Charges

However, some dissident Soviet revisionists – such as Roy Medvedev* charged in the 1960s that

” wrecking… was comparatively insignificant.”

Roy A. Medvedev: ‘Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism’: London; 1971; p. 112).

and attributed the Shakhty case to, the need to find a scapegoat for the economic consequences of Stalin’s alleged

” serious mistakes.”

Roy A. Medvedev: ibid.; p .110

And

“such a scapegoat was found: the specialists, the intelligentsia”.

Roy A. Medvedev: ibid.; p. 110

Rebutting Evidence

Medvedev’s charge is refuted by a number of facts. For example, at his public trial in January 1937, Yuri Pyatakov* admitted participating in the organisation of economic sabotage:

“PYATAKOV: Sedov* said that only one thing was required of me, namely that I should place as many orders as possible with two German firms, Borsig and Demag, and that he, Sedov, would arrange to receive the necessary sums from them, bearing in mind that I would not be particularly exacting as to prices. If this were deciphered, it was clear that the additions to prices that would be made on the Soviet orders would pass wholly or in part into Trotsky’s hands for his counter revolutionary purposes…

VYSHINSKY: That means that you, Pyatakov, by virtue of an arrangement with Sedov, paid the Demag firm certain excessive sums at the expense of the Soviet government?

PYATAKOV: Unquestionably…

VYSHINSKY: You also paid Borsig excessively at the expense of the Soviet government?

PYATAKOV: Yes…

VYSHINSKY: What was your official position in 1933-34?

PYATKOV: I was Assistant People’s Commissar of Heavy Industry.

I have already testified that wrecking activities were developed in Ukraine, chiefly in connection with the coke and chemical industry.

Also in the Urals, criminal activities were being carried on in connection with the copper industry and the living conditions of the workers at the Central Urals Copper Construction, and in Krassno-Uralsk.”

Report of Court Proceedings in the Case of the Anti-Soviet Trotskyite Centre; Moscow; 1937; p. 26-28, 45. 46, 47

And Pyatakov’s admissions are independently confirmed by the testimony of American Mining Engineer John Littlepage, who worked in the Soviet Union in the 1930s and described his personal experience of such sabotage in a series of articles in the ‘Saturday Evening Post’ in 1937-38:

“On the basis of my own experience, I can testify that industrial sabotage is a commonplace in Soviet Russia.

While I was assigned to work in the copper mines, I had an opportunity to observe at first hand the actions of Yuri Pyatakov:1 the vice-commissar executed in 1937 after he had confessed to leadership of a wrecking ring, I went to Berlin in the spring of 1937 with a large purchasing commission headed by Pyatakov; my job was to offer technical advice on purchases of mining machinery. Some things happened on that occasion which I never understood until I read Pyatakov’s testimony at his trial in 1937.

Among other things, the commission in Berlin was buying several dozen mine hoists, ranging from 100 to 1,000 horse-power…. The commission asked for quotations on the basis of pfennigs per kilogram. After some discussion, the German concerns later mentioned in Pyatakov’s concession, reduced their prices between 5 and 6 pfennigs per kilogram. When I studied these proposals, I discovered that the firms concerned had substituted cast-iron bases weighing several tons for the light steel provided in specifications, which would reduce the cost of production per kilogram but increase the weight, and therefore the cost to purchaser.

Naturally, I was pleased to make this discovery and reported to the members of the commission with a sense of triumph. But these men were distinctly lukewarm; they even brought considerable pressure on me to persuade me to approve the deal. I couldn’t figure out their attitude. I finally told the commission members flatly that they would have to make the purchases on their own responsibility, and that I would see that my own contrary advice got on the record. Only then did they drop the proposal.

At the time, I attributed their attitude to obstinate stupidity, or perhaps some personal graft. But this incident was fully explained by Pyatakov’s subsequent confessions.. The matter was so arranged that Pyatakov could have gone back to Moscow and showed that he had been very successful in reducing prices, but at the same time would have paid out money for a lot of worthless cast iron and enabled the Germans to give him very substantial rebates. According to his own statement, he got away with the same trick on some other items, although I blocked this one.”

John D. Littlepage: ‘Red Wreckers in Russia’, in: ‘Saturday Evening Post’, Volume 210, No. 27 (1 January 1938); p. 10, 53-54

Littlepage describes a return visit in 1937 to some lead-zinc mines in Kazakhstan:

“I discovered that the property had gone along fairly well for two or three years after I had reorganised it in 1932. Then a commission came in from Pyatakov’s headquarters… My instructions had been thrown into the stove, and a system of mining introduced throughout these mines which was certain to cause the loss of a large part of the ore body in a few months…

One of the most flagrant examples of deliberate sabotage involved a rather elaborate ventilating system which had been ordered for the lead smelter… This ventilation system, which cost a lot of money and was necessary to protect the health of workers in the smelter, had been installed in the filter section of the mill, where there were no harmful gases or dust of any kind. Any engineer would agree that such action could hardly be the result of mere stupidity, however gross.

I went through this plant thoroughly, and drew up my report, explaining how the written instructions I had left behind me in 1932 had disappeared some time in 1934. When I submitted this report, I was shown the written confessions of the young engineers I have mentioned above… Their confessions explained just how and when the ‘mistakes’ had occurred which I had outlined in my report. They admitted that they had been drawn into a conspiracy against the Stalin regime by opposition Communists.”

John D. Littlepage: ibid, p. 54

Littlepage’s testimony on sabotage on behalf of ex-capitalists is confirmed by other foreign experts who worked in the Soviet Union, such as the American John Scott. Speaking of the ex-owners., he says:

“The machines were. symbolic of the new power, of the force which had confiscated their property. And they struck at the machines.”

John Scott: ‘Behind the Urals: An American Worker in Russia’s City of Steel’; London; 1942; p. 149

Lessons of the Shakhty Affair

At a Plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU in April 1928,

“Rykov… reported on the Shakhty affair.”

Kendall E. Bailes: op. cit.; p. 84

and a resolution was adopted declaring that the Shakhty case signified

“new forms and new methods of bourgeois counter-revolution against proletarian dictatorship and against socialist industrialisation”.

Resolution of CC Plenum, CPSU: in: Hiroaki Kuromiya: ‘Stalin’s Industrial Revolution: Politics and Workers: 1928-1932, Cambridge; 1990; p. 15

Already by May 1928, Stalin was drawing from the Shakhty affair the lesson that Communists must master technical science for themselves:

“The Shakhty affair … was the expression of a joint attack on the Soviet regime launched by international capital and the bourgeoisie in our country.

From this follows the immediate tasks of our Party: to enhance the readiness of the working class for action against its class enemies…

We must master science, we must train new cadres of Bolshevik experts in all branches of knowledge.”

Josef V. Stalin: Speech at 8th Congress of the All-Union Young Communist League (May 1928), in: ‘Works’, Volume 11; Moscow; 1954; p. 73, 74. .82

Adding a year later, the need to develop higher vigilance among the working class against the machinations of its class enemies:

“As a result of the Shakhty affair, we raised in a new way the question… of training Red experts from the ranks of the working class to take the place of the old experts…

The Shakhty affair … revealed that the bourgeoisie was still far from being crushed, that it was organising and would continue to organise wrecking activities to hamper our work of economic construction; that our economic, trade-union and, to a certain extent, our Party organisations had failed to notice the undermining operations of our class enemies, and that it was therefore necessary to exert all efforts and employ all resources … to develop and heighten their class vigilance.”

Josef V. Stalin: Speech at Plenum of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission of the CPSU (b) (April 1929), in: ‘Works’, Volume 12; Moscow; 1955; p. 12, 13

Stalin emphasised both these lessons in his speech of February 1931 on ‘The Tasks of Business Executives’:

“The Shakhty affair was the first grave warning. The Shakhty affair showed that the Party organisations and the trade unions lacked revolutionary vigilance. It showed that our business executives were disgracefully backward in technical knowledge, that some of the old engineers and technicians, working without supervision, rather easily go over to wrecking activities, especially as they are constantly being besieged by ‘offers’ from our enemies abroad…

Of course, the underlying cause of wrecking activities is the class struggle. Of course, the class enemy furiously resists the socialist offensive. This alone, however, is not an adequate explanation for the luxuriant growth of wrecking activities.

How is it that wrecking activities assumed such wide dimensions? Who is to blame for this? We are to blame…

Had we started much earlier to master technique, had we more frequently and efficiently intervened in the management of production, the wreckers would not have succeeded in doing so much damage…

The task is for us to master technique ourselves… This is the sole guarantee that our plans will be carried out in full.”

Josef V. Stalin: ‘The Tasks of Business Executives’ (February 1931), in: ‘Works’, Volume 13; Moscow; 1955; p. 38, 391 40

Published by:

THE MARXIST-LENINIST RESEARCH BUREAU,

at Address of Bland.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AVTORKHANOV, Abdurakhman: ‘Stalin and the Soviet Communist Party: A Study in the Technology of Power’; Londonj 1959.

BAILES, Kendall E.: ‘Technology and Society under Lenin and Stalin: Origins of the Soviet Technical Intelligentsia: 1917-19411; Princeton (USA); 1978.

BERMAN, Harold J. (Ed.): ‘Soviet Criminal Law and Procedure: The RSFSR Codes’; Cambridge (USA); 1966.

CARR, Edward H, & DAVIES, Robert W.: ‘Foundations of a Planned Economy! 1926- 1929’, Volume 1; London; 1969.

COHEN, Stephen F.: ‘Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography: 1888-1938’; London; 1974.

CONQUEST, Robert: ‘The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties’; London;

1973.

KUROMIYA, Hiroaki: 1Stalin1s Industrial Revolution; Politics and Workers:

1928-1932′; Cambridge; 1990.•

LITTLEPAGE, John D.:· ‘Red Wreckers in Russia’, in: ‘Saturday Evening Post;,

Volume 210, No. 27 (1 January 1938).

LYONS, Eugene: 1 Assignment in Utopia 1; London; 1938.

MEDVEDEV, Roy A.: ‘Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism’; London; 1971.

SCOTI’, John: ‘Behind the Urals: An American Worker in Russia’s City of Steel,.;

London; 1942.

STALIN, Josef V.: ‘Works’, Volume 11; Moscow; 1954. STALIN, Josef V.: ‘Works’, Volwne 12; Moscow; 1955. STALIN, Josef V.: ‘Works’; Volume 13; Moscow; 1955.

STETSKOVSKY, Yuri: ‘The Right of the Accused to Defence in the USSR’; Moscow;

1992.

STROGOVICH, Mikhail S..: ‘Kurs sovetskogo ugolovnogo protsessa1 (Course of Soviet Criminal Procedure)’; Moscow; 1968-70..

TROTSKY, Leon: ‘Pro,blems of Development of the USSR’• in: ‘Writings of Leon

Trotsky (1930-31)’: New York; 1973.

TUCKER, Robert C.: ‘Stalin in Power: Th-e Revolution from above: 1928-1941’:

New York; 1990.

Report of Court Proceedings in the Case of the Anti-Soviet Trotskyite Centre; Moscow; 1937.

‘Great Soviet Encyclopedia’, Volume 29; New York; 1982.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

BUKHARIN, Nikolay I , Soviet revisionist politician (1888-1938); editor, ‘Pravda.'(1924-29); Chairman, Communist International (1926-29); editor, ‘Izvestia’ (1934-37); expelled from Party and arrested (1937); convicted of treason and executed (1938).

KAGANOVICH, Lazar M., Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1893-1991); 1st Secreta.ry, GP Ukraine (1925-28); secretary, CPSU (1928-35); 1st Secretary, Moscow Region CPSU (1930-35); USSR People’s Commissar of Tran.sport (1935-37, 1938-42); USSR Peopleis Commissar of Heavy Industry (1937-39); USSR Deputy Premier (1938, 1944-46); USSR People’s Commissar of Fuel In.dustry (1939-41); memhe”I· 1 State Defence Committee (1941-44); USSR Minister of Building Materials Industry (1946-47, 1956 57); USSR Deputy Premier (1947-55); 1st Secretary CP Ukraine (1947-53); manager, Sverdlovsk Cement Works (1957-63).

KRYLENKO, Nikolay V., Soviet revisionist lawyer (1885-1938); RSFSR People’s Commissar of Justice (1931-36); USSR People’s Commissar of Justice (1936- 37); arrested and convicted of treason (1937); died in prison (1938).

LYONS, Eugene, Russian-born American journalist (1898-1985); to USA (1907); editor, TASS news agency, New York (1924-27); United Press correspondent, Moscow (1928-34)r editor, ‘American Mercury’ (1939-44); editor, Pageant, (1944-45) editor, ‘Readers’ Digest’ (1946-75)

MEDVEDEV, Roy A., Soviet revisionist historian (1925- ); deputy editor Publishing House of Educational Literature (1957-61); departmental head, Research Institute of Vocational Literature (1962-71); free-lance writer (1971- ).

MENZHINSKY, Vyacheslav P., Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1874-1934); Deputy Chairman, OGPU (1923-25); Chairman, OGPU (1926-34); assassinated by revisionist. conspirators (1934).

PYATAKOV, Georgi (Yuri) L.1 Soviet revisionist economist and politician (1890- 1937); Deputy Chairman, State Bank (1928-33); USSR Deputy People’s

Commissar of Heavy Industry (1933-34)i expelled from CP (1936); convicted of treason and executed (1937).

RYKOV, Alexsey I., Soviet re.visiionist politician (1891-1938); RSFSR Premier (1924-29); USSR Premier (1930-31); USSR People’s Goromissar of Communications (1931-36); expelled from Party and arrested (1937); convicted of treason and executed (1938).

SEDOV, Leon, Soviet revisionist politician (1905-38); Trotsky’s son conspirator; in exile with Trotsky (1929); editort ‘Bulletin Oppositio,n; (1928-38); to Germany (1931); to France (1933); died in French hospital (1938).

TOMSKY, Mikhail P., Soviet revisionist trade-union leader and politician (1880-1936)-; committed suicide (1936).

VYSHINSKY, Andrey I., Soviet Marxist-Leninist lawyer, diplomat and politician (1883-1954); Rector, Moscow University (1925-28); RSFSR State Prosecutor (1931-33); USSR Deputy State Prosecutor (1933-35) i USSR State Prosecutor (1935-39); USSR Deputy Premier (1939-44); USSR Deputy People’s Commissar/Minister of Foreign Affairs (1940-49); USSR Minister of Foreign Affairs (1949-53); USSR Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (1953); USSR Representative at UN (1953-54).