Exhibition Review: “Photography and the Black Arts Movement 1955-1985”

James E.Hinton “Two women sitting on a New York subway”; 1966

This image taken at the exhibition

Exhibition Review: “Photography and the Black Arts Movement 1955-1985”; at National Gallery of Art (NGA) Washington DC to 11 January, 2026 – free entrance.

After 11 January, 2026 – the exhibition is at J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, February 24–June 14, 2026; and;

Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson, July 25–November 8, 2026;

Curated by Black photography historian, Dr. Deborah Willis and Philip Brookman, curator for photography at the National Gallery of Art .

The USA in arts and an exhibition in National Gallery of Art in Washington DC

Trump’s cultural fist has knuckled down on African-American art and museums. Including depictions of history in USA. In the autumn a famous photograph of the horrors of slavery historically used by abolitionists was removed from display:

“In 1863, at the height of the Civil War. . . an image of a former slave’s horrifically scarred back. . . shocked white Americans across the Union. Now that photo is among dozens of exhibits about slavery at several national parks, . . . ordered removed by the Trump administration. . . at the Harpers Ferry National Historic Park in West Virginia and George Washington’s old house in Philadelphia, where the first U.S. president kept nine slaves.”

Io Dodds; “National park to remove exhibit of famed photograph showing former slave’s scarred back, says report” ; The Independent London; 16 September 2025 At: Independent

That photo of former slave Peter Gordon who escaped from Mississippi is known as “The Scourged Back”. Arriving at a Union Army camp in Louisiana in 1863, two photographers, McPherson and Oliver, documented the results of repeated whippings. The moves are a part of President’s Trump’s attempted sanitising of USA history:

“The directives stemmed from President Trump’s executive order in March that instructed the Park Service to remove or cover up materials that “inappropriately disparage Americans,” part of a broader effort by Mr. Trump to promote a more positive view of the nation’s history.”

Maxine Joselow ; NYT “Park Service Is Ordered to Take Down Some Materials on Slavery and Tribes”; Sep 16, 2025.

In the most recent episode of his egotistical mania the “Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts” at Washington is renamed the “Trump-Kennedy Center”.

In such a cultural desert-climate, it is good to see the exhibition reviewed below. We strongly recommend progressives in the Washington DC area see it before January 11 2026; or those in the California or Mississippi area when it exhibits there.

What the exhibition tries to do

Unusually perhaps – contrary to the usual self-promoting ‘hype’ on museum websites – the pages at the AGA are very informative. The National Gallery Art (AGA) ‘blurb’ at its website announces that the exhibition “considers photography’s impact on a cultural and aesthetic movement that celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty”:

“The first exhibition to consider photography’s impact on a cultural and aesthetic movement that celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

Uniting around civil rights and freedom movements of the 1960s and 1970s, many visual artists, poets, playwrights, musicians, photographers, and film-makers expressed hope and dignity through their art. These creative efforts became known as the Black Arts Movement.

Photography was central to the movement, attracting all kinds of artists—from street photographers and photojournalists to painters and graphic designers. This expansive exhibition presents 150 examples tracing the Black Arts Movement from its roots to its lingering impacts, from 1955 to 1985. Explore the bold vision shaped by generations of artists including Billy Abernathy, Romare Bearden, Kwame Brathwaite, Roy DeCarava, Doris Derby, Emory Douglas, Barkley Hendricks, Barbara McCullough, Betye Saar, and Ming Smith.“

NGA at Black Art Movement

This the exhibition does. As another reviewer puts it:

“photography is not passive. It acts. It intervenes. It gives form to worlds that dominant structures attempt to obscure. For the artists of the Black Arts Movement, photography was not merely a medium of expression; it was a method of liberation. This exhibition, therefore, is more than a historical survey—it restores photography to its rightful place within one of the most transformative artistic and political movements of the twentieth century. It reframes a revolutionary moment by revealing the images that helped create it and invites viewers to consider how photography continues to shape the ongoing struggle for representation, justice, and cultural self-definition.”

Çisemnaz Çil Musee; November 24 “Photography And The Black Arts Movement | The National Gallery Of Art”: at: Musee

That is to us an excellent summary of why progressives today should see this exhibit.

How is the Black Arts Movement defined?

But what is the “Black Arts Movement”?

This took place well after the much more recognised so-called ‘Harlem Renaissance’ of the 1920s era. The term was given by a poet, Larry Neal for a “cultural revolution” in the 1950s:

“Poet Larry Neal. . . coined the term Black Arts Movement. . . (for) “a cultural revolution in art and ideas.” This movement included poets, playwrights, musicians, filmmakers, photographers, and painters. They came together to make art that advanced civil rights and celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty. This cultural revolution shook up the art world in the 1950s and ’60s. It embodied the struggle for self-determination championed by global freedom movements. New collectives, workshops, and collaborations emerged. Creatives made art that promoted Black dignity, hope, and freedom. They asked, how could art inspire social and political change? And what would it look like?”

Photography was a driving force from the beginning, playing a critical role as both a communications tool and art form.”

NGA at Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985; Ibid.

Situating the birth of the Black Arts Movement – battles over ‘separate but equal’

The timing of the Black Arts Movement’s birth, locates it squarely in the civil rights movement of the late 1950s-1960s. It followed the brutal killing of Emmet Till in August 1955. The courageous decision of his mother to show the murdered boy – with all his wounds – in an open casket set in motion a chain of events:

“In September, Jet magazine was one of several publications that printed open-casket photographs of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was lynched in Mississippi. Those disturbing images were seen across the country, including by a woman in Montgomery, Alabama: Rosa Parks. That December, Parks sat in the front, “white only” section of a segregated bus. The driver demanded that she give up her seat to a white passenger. She refused. As she later recounted, Emmett Till was on her mind in that moment. Parks, in turn, was photographed sitting at the front of the segregated bus.”

“What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know” at this NGA site

The fight for African-American rights entered a new phase. Segregation of races had been enshrined by the USA state in the infamous dictum ‘separate but equal” as in the decision of the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson of 1896. That stemmed from the refusal of Mr. Homer Plassey – a black man – to move from a ‘white only’ railway seat. It sealed the vicious so-called ‘Jim Crow’ societal norms. (Britannica Plesse v Ferguson).

It was only in 1954 that the Supreme Court reversed Plessy in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (at Britannica Topeka Brown v Board):

“on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously (9–0) that racial segregation in public schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibits the states from denying equal protection of the laws to any person within their jurisdictions. . . Although the 1954 decision strictly applied only to public schools, it implied that segregation was not permissible in other public facilities. . .”

Ibid

But the Court did not “simply” hand it over. Progressives know that such decisions are not ‘given’ to the working class. It had been bitterly fought for. Over years – from the the 1940s-1950s as Encyclopaedia Britannica records, starting :

“In the late 1940s the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began a concentrated effort to challenge the segregated school systems in various states, including Kansas. There, in Topeka, the NAACP encouraged a number of African American parents to try to enroll their children in all-white schools. All of the parents’ requests were refused, including that of Oliver Brown. He was told that his daughter could not attend the nearby white school and instead would have to enroll in an African American school far from her home. The NAACP subsequently filed a class-action lawsuit. . . A number of students at the all-Black school were plaintiffs in the lawsuit Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1952).

In October 1952 the Court consolidated Brown with three other class-action school-segregation lawsuits filed by the NAACP. . . The plaintiffs in Brown, Biggs, and Davis appealed directly to the Supreme Court.“

Britannica Brown v Board

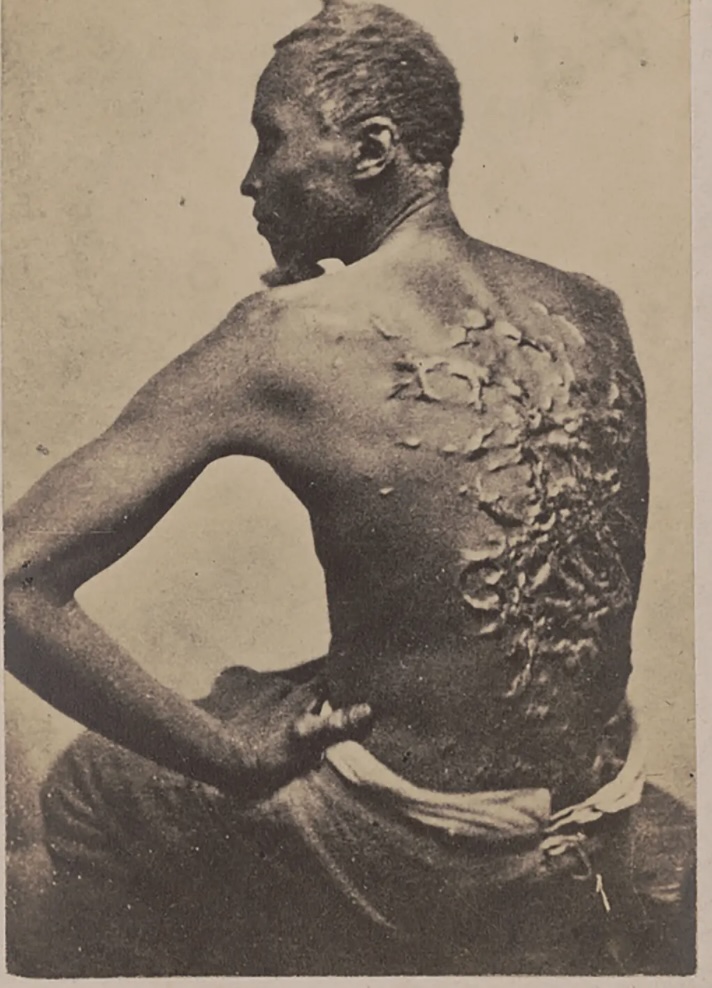

The “Little Rock Nine” of Arkansas included Elizabeth Ann Eckford who claimed their right to education in 1957. They walked lines of harassment to attend classes in previously all-schools.

Elizabeth Ann Ecford; pictured by Will Counts – not in exhibition – At wikipedia

The progressive role of the photographs

This all led up to the major fight for voting rights in Montgomery and Selma Alabama. The initial voter registration drive, was started in 1963 by the African-American Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). As the excellent catalogue explains:

“Two key points of disenfranchisement made voter registration difficult for Black Americans in the South during the mid-1960s: state legal frameworks based on Jim Crow and campaigns of terror waged by state and local officials, law enforcement and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)” ;

Philip Brookman’ “The Messenger”; in ‘Photography and the Black Arts Movement 1955-1985”; p. 29; Yale 2025;

Moneta Sleet “Two teenage supporters Selma Marchers 1965”;

Perhaps one highlight in the Exhibition is the work of Gordon Parks – already famous and likely known to many readers with his work. He went to Alabama in 1955-56 retained by ‘Life’ magazine looking at the societal quakes on the ground. A six-part article “Background of Segregation” included his pictures. However many other photographers other were there, and Doris Derby, Bob Fletcher, Maria Varela and others – were often given camera equipment and taught to use it.

“Images of the movement – both positive and negative, color and black-and-white – brought what was happening into the living rooms of millions of Americans. The SNCC’s leaders – John Lewis, James Foreman, Stokely Carmichael – all understood the power of visual media, public relations, and how pictures could help sway public opinion. . . Throughout the 1960s leaders at the SCLC, SNCC, Nation of Islam, Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Black Panther Party, and Young Lords – all understood how photography could transform their movements”.

Philip Brookman’ “The Messenger”; in ‘Photography and the Black Arts Movement 1955-1985”; p.27; 30; Yale 2025;

This is not to support organisations such as ‘Nation of Islam’ which should be categorised as ‘black racist’ (See MLRG.online Nation of Islam). We have elsewhere argued that there is no black nation in the USA – that there is one class struggle. Nonetheless these currents were all aware of the importance of documenting a renewed movement for civil rights for African American – Black Americans.

Connecting the dots to the larger movement

The broader Black revolutionary movement is evident throughout this exhibition. The transition from a banjo playing African-American to lynchings and – to resistance – is shown by Bettye Saar.

Bettye Saar, “Let me entertain you”; 1972

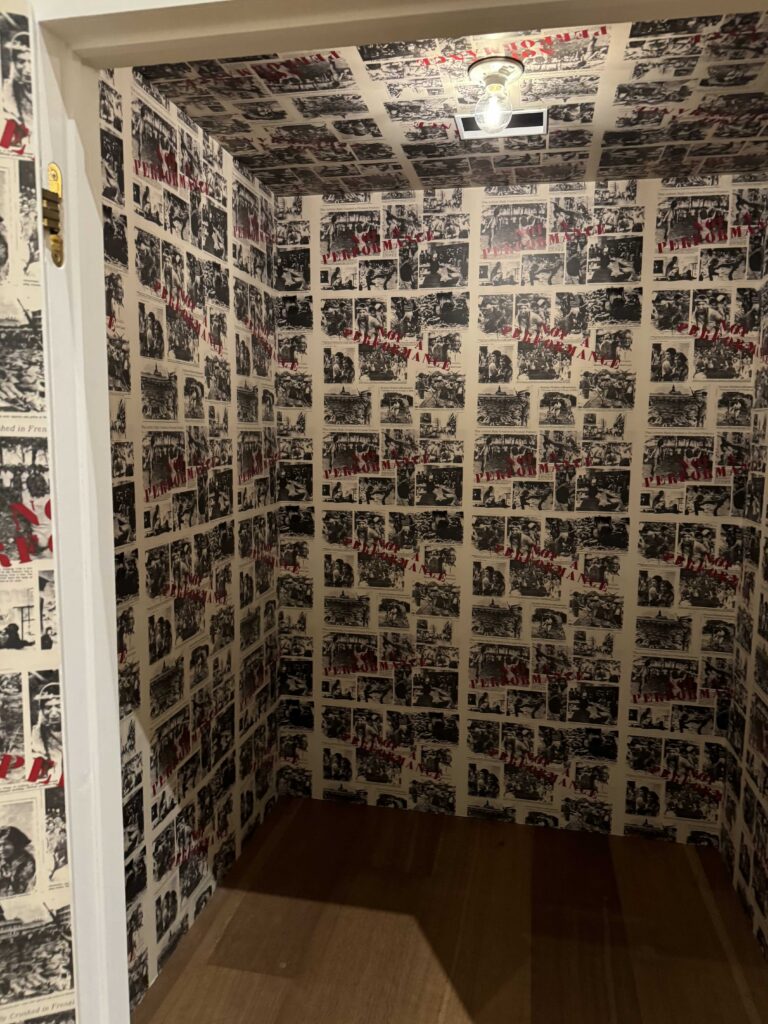

A riveting exhibit was a small booth of photo-collages from newspaper clippings and photos. These show wars, uprisings, and natural disasters. The booth is erected allowing you to walk in, and with all collages marked in red as “not a performance” – by Adrian Piper 1976 – lit by a single naked light bulb inside.

To conclude – enough is shown by now to convince of seeing this powerful exhibition. If you cannot go consider getting your library to get the catalogue, or if you can – buy it.

Hari Kumar 21 December 2025.