Blaring Trumpets, Banging Drums: Dmitry Shostakovich and Politics of Music 1917-1953 in the USSR

September 24, 2025; minor amendments, and extra image added September 27;

September 28, An added section is in Introduction denoted with * *- due to late receipt of a book being Isaak Glikman’s “Letters”. These amendments do not alter any trend in my statements, but strengthen them.

Dmitry Shostakovich and Politics of Music 1917-1953 in the USSR – Part One

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Dmitry Shostakovich – Politics of music 1917-1953 in the USSR

Preface

acknowledgements

1. Introduction

Shostakovich’s musical gifts

Some selected statements from the composer

Puzzles surrounding Shostakovich

“Cold War” pictures fabricated by Solomon Volkov’s “Testimony”

A life summary of Shostakovich

Sources

The overall plan of this article

Part One: On aesthetics and the art movements in the USSR up to 1932

2. Aesthetics – Development of music, and the balance of content and form in art

The origins of music

Form and content of art in general

Deviations from Marxism in politics

Deviations from Marxist views in art and aesthetic theory

The problems of interpretating music

An introduction to the Formalism Debate of 1948

How revisionists and Marxist-Leninists fought ideological battles in the USSR

3. Culture and art movements after the Bolshevik Revolution (1917-1930)

‘Proletarian Culture’ (1917-24)

The Narkompros (Commissariat of Education and Enlightenment) under Anatol Lunarcharsky (Lunarcharskii)

The appointments of Mikhail Porovsky and Alexsandr Bogdanov

The scope of Narkompros

Krupskaia (Krupskaya) and Illiteracy

Battles of Lunarcharsky against the ultra-lefts led by Kerzhentsev

The formation and growth of Agitprop

The arts or cultural front and Narkrompros

4. The politics of the ‘expert’ – Communist Academy and Proletkult

The Ultra-Left movements in the arts 1917-1930

The Communist Academy

Attacks on bourgeois specialists

Pokrovsky and the discipline of history

Proletkult (Proletarian Cultural and Educational Organization)

5. Lenin’s 1920 confrontation with the ultra-leftists

The Bolshevik state, Lenin, Trotsky and the Proletkult

Lenin disputes Lunarcharsky and Bukharin at the 1920 First Proletkult Conference

6. The period of State ‘neutrality’ on art

After Lenin’s death a Leninist view on Art put by Stalin is rejected by the Party Leadership

The Russian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP)

RAPP and the suicide of Mayakovsky

Ultra-leftism following the 1920 exposure of Proletkult by Lenin

7. The Marxist-Leninist rejection of ultra-leftism – to socialist realism

The 1932 Party Decision ‘On the Reformation of Literary-Artistic Organisations’

The Origin and characteristics of the Term ‘Socialist Realism

The question of tendentiousness in Marx and Engels’ time and in the USSR

The First Congress of Soviet Writers (1934)

8. The music organisations after 1920

The ‘Kuchka’ – the Great Five Russian composers

RAPM and simplicity in Music and anti-gypsy music

ASM (Association for Contemporary Music)

RAPM (the Russian Association of Proletarian Composers– (or Musicians)

ORKiMD – the ‘Association of Revolutionary Composers and Musical Activists’

Agitprop and Platon Kerzhentsev

Production Collective of Moscow Conservatory Students (Prokoll)

RAPM and Prokoll – “Monopolistic power on the musical scene”

RAPM takes the upper hand

Kerzhentsev’s Attack on Vsevold Meyerhold

Shape-shifting Kerzhentsev adopts ‘professionalism’ at ‘Leningrad Theatre of Working Youth’ (TRAM)

Dismantling RAPM and The Creation of the All Russian Union of Soviet Composers

Part 2 will follow shortly

Preface

At this time the world is undergoing a profound crisis of the capitalist system. One which unleashes a massive assault on the working peoples of the world. Some will question having a detailed article on the music history of the USSR at this time. Maybe this is a complete irrelevance for the world’s toilers and Marxist-Leninists? In a way, that simply cannot be disputed.

However questions of art in society are central to Marxist views as to how to change society. Matters of socialist aesthetics, and the socialist history of revisionism in the USSR continue to be very relevant.

Prior tellings of Shostakovich’s story in my view usually fall into a reductionism. These two areas – aesthetics and history of revisionism – join in some revealing ways in Shostakovich’s career. I believe the story bears telling – even now at this dire and crisis laden stage. Since this version may be controversial in Marxist-Leninist circles, I will use the personal pronoun.

Acknowledgements

Before going to the text, I should emphasise that I am not a musician or a musicologist. Hence this is not the best possible dissection of Shostakovich. I suggest the work is best viewed as a history of another ‘small’ chapter of hidden revisionism in the USSR. We must await a more musical Marxist-Leninist dissection on the musical scores and techniques – especially on Shostakovich’s chamber music.

Nonetheless over 50 years I have benefited from the musical insights of a good comrade. JP is an accomplished musician, able to coax music out of accordions, French horns, piano, tin-whistle, bagpipes . . . and drums at many a demonstration. Recently, I benefitted from an amendment made by Marv Gandall to a discussion on definitions of ultra-leftism. Marv is a Trotskyist, yet we have shared both agreements and disagreements over years. Lastly but not least, unquestionably the largest influence on my work has been W.B.Bland. His systematic and prescient exposure of revisionism in the USSR laid the basis for my much later and much more pedestrian thinking.

- Introduction

2025 is the 50th anniversary of the death of Dmitry Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (1906-1975). Currently his opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” from 1934 is being revived in several opera houses over the world. Marxists of all shades for years have faced several questions on Shostakovich. These at core include the role of the socialist state in art; and on Shostakovich’s attitudes inside a socialist state.

Whether Shostakovich was a convinced communist – particularly by the end of his life is unclear. At least to me. Bourgeois musicologists are divided on this matter. Some say Shostakovich was a life-long communist, still others that he was a hidden enemy of communism forced to write in code. Meanwhile Marxists differ as well. Followers of L.D. Trotsky allege that Shostakovich was repressed by J.V. Stalin, and his art was cramped by the party. Marxist-Leninists include those who believe Shostakovich became a worthy musical practitioner only after intense criticism. Others of both left and right, claim that he was only an opportunist pretending to be a socialist musician.

This piece will argue that understanding the career of Shostakovich can only emerge from situating him within the battles of revisionism against the socialist state. Bland outlined the hidden rise of revisionism inside the USSR. In part of that rise, he stated that the Yezhovschina directed a wide miscarriage of justice. It was possible to disguise this as being “justified” – as there were indeed, hidden revisionist traitors at all levels of the Party.

This Revisionism at various times was expressed in various ultra-left positions taken up in the arts. Starting with open and evident movements such as Proletkult, and later RAPM. After 1932, open revisionism was not feasible. Its adherents then were forced to work more secretively, as exemplified by the figure of Platon Krezhentsev. This article will follow this trail.

Already this battle against hidden revisionists introduces a confusing picture. Unsurprisingly then the picture of Shostakovich is blurred by many conflicting images. At two polar ends there is usually a cut-out stereotype. At one end is a picture of the victimised composer hiding from a vengeful Stalin – who was forced to write to order. At the other is a convinced, bluntly socialist-realist communism disguised in music.

Part of the blurring stems from bourgeois propaganda. Part stems from a 1936 attack prompted by a disgruntled ultra-Leftist remnant of the Proletkult – Krezhentsev. As the reader will find, he was the most likely author of the Pravda article “Muddle not Music” – not Stalin.

Shostakovich’s musical gifts

Even those taking extreme opposite views on Shostakovich, widely acknowledge that at his best, he expressed human emotions vividly. Some of his extraordinary music includes Symphony 5 (A Musician’s Reply To Just Criticism); Symphony No. 7 (The Leningrad); Symphony No.13 (The Babi Yar); his piano Preludes and Fugues; and his string quartets.

That short list includes music appreciated by socialists, but also music claimed by non-socialists. Many anti-communists for example, identify as “anti-Soviet” music, the 13th Symphony, the Babi Yar. That sets to music the words of poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. It is of course true that Yevtushenko was an anti-Stalinist (Obituary New York Times). However the words in ‘Babi Yar’ excoriate anti-Semitism, praise the mettle of Russian women, and the courage of Galileo (Libretto). Not anti-communism as far as I can see.

If Shostakovich’s music speaks to a progressive vantage point, and is meaningful to listeners – does the composer’s own underlying beliefs matter? Marxist-Leninists generally respond by arguing that even with a progressive content, the style of music composition by Shostakovich is “formalist”, “hard” and “inaccessible”. But – even “Lady Macbeth of Mtensk” was popular in the USSR.

The distinction between form and content will be discussed. But what is “formalism”? It is known that Shostakovich received frank – even harsh – criticism by the CPSU(B) on these grounds. A further charge against him was that the proletarian audience could not understand much of his work.

Some Liberals will argue that in any case, it is irrelevant what it is meant by ‘formalism’. Their position is that it is an artists’ ‘right’ for their work to be beyond any state criticism. That position is one of a right for ‘art for art’s sake’. Trotskyists do not generally go so far, and most of them will agree that art is socially conditioned. But they will then – if they follow Trotsky faithfully – say the workers state has to be neutral in matters of art. Marxist-Leninists argue in contrast that a socialist state – or a state constructing such a society – has all rights to proffer criticism and guidance for benefits of state support.

Few Marxists will quarrel with Karl Marx and Frederich Engels when they say:

“Does it require deep intuition to comprehend that man’s ideas, views and conceptions, in one word, man’s consciousness, changes with every change in the conditions of his material existence, in his social relations and in his social life?”

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, “The Communist Manifesto”; CW Volume 6; Moscow 1976; p. 503-04

Is it really then too far a step, then to the view from Stalin about a part of the cultural front in the USSR?

“Comrade Stalin has called our writers engineers of human souls.”

Andrey A. Zhdanov: ‘Soviet Literature – the Richest in Ideas, the Most Advanced Literature’ in: H. G. Scott (Ed.): ‘Problems of Soviet Literature’; London; 1935; p. 21

Yet that phrase is often mocked by both bourgeois and Trotskyist writers.

So much for now, on the right of the state to proffer criticism. But one other point about whether his music was comprehensible, and the role of external criticism is worth considering.

Comparisons may be invidious, but recall that Ludwig van Beethoven’s music was frequently met with incomprehension in his lifetime. Including even the great 9th Symphony, or his quartets (Reception of Beethoven). Furthermore, Beethoven received severe musical criticism through his career. And on at least one notable occasion of the initially failed opera ‘Leonore’ later to become the famous ‘Fidelio’ – he was subjected to a concerted group revision and critique by friends and musicians:

“Not a note will I cut!” Beethoven kept shouting, as proposals for improvement were made. The entire opera was gone through, piece by piece, note by note, with frequent repetition. The group pleaded and cajoled; Beethoven resisted at every point. It was well past midnight before the end was reached. . . The net result was a reworked opera in two acts, and an entire aria was dropped.”

John Suchet; “Beethoven – The Man Revealed”; New York 2012; p.167-8

Some selected statements from the composer

Still, a blurred picture of Shostakovich is what we face. Can Shostakovich’s own remarks focus our view of the composer? It is often presented that the composer was often reluctant to clarify “explanations” of his work.

While to an extent this is true, a large corpus of his own thoughts does exist. Especially in the context of interviews. Many completely discount these sources from the Soviet media, as being merely words said to kow-tow to the Party (This is discussed further in the section below on sources). However it is unreasonable to throw out all these materials from his various numerous several interviews.

These following quotes are his own words and are of interest:

“’When a critic, in Rabochiy i Teatr or Vechernyaya krasnaya gazeta, writes that in such-and-such a symphony Soviet civil servants are represented by the oboe and the clarinet, and Red Army men by the brass section, you want to scream!”

Dmitry Shostakovich; ‘Sovetskaya muzika Pnaya kritika otstayot’ [Soviet music criticism is lagging], Sovetskaya Muzika (3/1933), 121; cited by: Richard Taruskin; “Public lies and unspeakable truth interpreting Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony”; in Fanning D (Ed); “Shostakovich Studies”; Cambridge Ibid; p.53

“Young Shostakovich delivered this harsh verdict, “This is why we consider Scriabin as our bitter musical enemy. Why? . . . Because Scriabin’s music tends towards unhealthy eroticism. Also to mysticism, passivity, and a flight from the reality of life.“

“In an interview granted to The New York Times in December 1931,

“There can be no music without ideology. . . We, as revolutionaries, have a different conception of music. Lenin himself said that ‘music is a means of unifying broad masses of people’. It is not a leader of masses, perhaps, but certainly an organizing force! For music has the power of stirring specific emotions . . . Even the symphonic form, which appears more than any other divorced from literary elements, can be said to have a bearing on politics . . . Music is no longer an end in itself, but a vital weapon in the struggle. Because of this, Soviet music will probably develop along different lines from any the world has ever known.”

The New York Times, 20 December 1931; cited by Boris Schwarz; “Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia: Enlarged Edition, 1917-1981”; p. 78;

“Asked what spectator he had written this for [“Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk’ -Ed], Shostakovich commented, “I live in the USSR, work actively and count naturally on the worker and peasant spectator. If I am not comprehensible to them I should be deported.”

Fay, Laurel E. Shostakovich: a Life”; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, p.55.

“Dmitri Dmitriyevich said pensively, “Of course – Fascism. But music, real music, can never be literally tied to a theme. National Socialism is not the only form of Fascism, this music is about all forms of terror, slavery, the bondage of the spirit.“

Elizabeth Wilson, citing Flora Litvinova recalling a conversation in 1941 on the 7th Symphony – in Kuibyshev having been evacuated from Leningrad; in “Shostakovich – A Life Remembered”; London 1994; p.158-9

*”“31 December 1943 Moscow: “Dear Isaac Davïdovich. . . The freedom loving peoples will at last throw off the yoke of Hitlerism., peace will reign over the whole world, and we shall live once more in peace under the sun of Stalin’s Constitution”. Of this I am convinced and consequently experience feelings of unalloyed joy.”

Isaak Glikman; “Story of a Friendship: The Letters of Dmitry Shostakovich to Isaak Glikman 1941-1975; and Commentary”; Cornell U Press 2001; p. 23 (69/376)”*

*”28 December, 1955, Moscow: Dear Isaac Davïdovich. . . Chekhov wrote (I paraphrase). . . A write must never assist the price or the gendarmerie”. . .

As Shostakovich writes he cites “Chekhov “springing” to defence of slanderously accused Dreyfus”

Isaak Glikman, “Story of a friend; p.62-63 (108/376)*

Of course these are selected quotes. They fail thus to give a complete picture of the composer. But they certainly do not give the impression of a dyed-in-the-wool anti-communist. *Rather what seems likely is a Communist in spirit, who became over time, disillusioned.* I believe a general picture emerges of a gifted musician, aware of the social context, who at first struggled to find an appropriate form in which to express his content. Certainly he was not content to stay in old forms or within old contents. But he was also grappling with a sense of “bondage of the spirit“. He then retreated into a private musical world.

Puzzles surrounding Shostakovich

The several puzzles include these:

i) “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” contains a central progressive theme – the oppression of women (including rich merchant class women) in pre-revolutionary Russia. If so why was it condemned?” Did Stalin write the ‘Pravda” articles that attacked Shostakovich? Was the popular reception of the opera in Russia hostile or otherwise?

ii) Why during the controversy over “Lady Macbeth” – did Maxim Gorki a chief supporter of Socialist Realism – come to the aid of Shostakovich – as follows?

“In March, Maxim Gorky—influential cultural and social figure and, significantly, the chief literary conceptualizer of Socialist Realism—used his personal access to Stalin to express his indignation at the destructive campaign:

‘Shostakovich is young, twenty-five [sic] years old, an unquestionably talented man, but very self-assured and quite high-strung. The Pravda article hit him just like a brick on the head, the chap is utterly crushed… “Muddle,” but why? What does this so-called “muddle” consist of? Critics should give a technical assessment of Shostakovich’s music. But what the Pravda article did was to authorize hundreds of talentless people, hacks of all kinds, to persecute Shostakovich. And that is what they are doing… You can’t call Pravda’s attitude to him “solicitous,” and he is deserving precisely of a solicitous attitude as the most talented of all contemporary Soviet musicians!”

Laurel E Fay; “Shostakovich: a Life”; New York; 2000; Chapter 6; p.91; citing M. Gorky, “Dva pis’ma Stalinu,” Literaturnaya gazeta (10 March 1993): 6.

iii) Why did Stalin, even after the major ‘Pravda’ attack on Shostakovich – support Shostakovich?

iv) Why was the official reception of the 7th and the 8th Symphonies of Shostakovich so different?

v) Why did A.A.Zhdanov launch an attack in 1948 on the Composers Union, including a named attack on Shostakovich? And yet. . . Why did Stalin continue to support Shostakovich after this?

vi) Why despite all the attacks on Shostakovich, did he win five Stalin Prizes; and also sit as a judge on the Stalin Prize Committee?

vii) What underlies his chamber music, and especially his string quartets? How much truth is that these are a prism of his personal and political anguish? What were these anguishes, if the string quartets do indeed express them?

viii) Why after not even applying to become a member of the CPSU(B) under Stalin’s lifetime, did he do so during N.Khruschev’s rule?

I do not think that Leftists coming from the Trotsky wing can resolve these contradictions satisfactorily. One attempt was made by Simon Behrman (“Shostakovich, Socialism, Stalin and Symphonies”; London nd; ISBN 9781905192663). I consider this book to fail at a historical level. But Behrman’s enthusiasm for music and his musical insights, in my view make this a very useful book. One that can be recommended to any calling themselves a Marxist. However it is not adequate. That is because it carries a political reductionism in two fundamental ways, which ultimately fails to unlock the Shostakovich story.

Firstly, on principle, Trotsky’s adherents deny the validity of any of the CPSU(B)’s criticisms against some of the more impenetrable aspects in some of Shostakovich’s works. Such Leftists usually end up denying any role of a socialist state – let alone the USSR to 1953 – in shaping a public art to help proletarians. Secondly another aspect stems from their particular theoretical reductionism. For they explain the history of the USSR, in some way as “Stalin’s megalomania” or “stupidity” etc. If this is what you believe – the classic Trotsky view – then there is of course, absolutely no need to probe further into the history of what happened. This convenience bars them from even seeing the role of personalities such as Kerzhentsev.

Appropriately Behrman’s view of the post-1917 revolutionary artistic fervor is absurdly simplistic:

“Along with the political gains of the revolution, the new culture that Trotsky referred to was also destroyed by Stalinism. The explosion of new art that immediately followed the revolution has become known as the Golden Age, a period that brought forth Symbolism and Futurism among many other cultural movements. The names of Rodchenko, Kandinsky, Eisenstein, Meyerhold and Mayakovsky are just some of the great artists of the 20th century indelibly linked with this period. However, by degrees this revolutionary ferment in art was gradually choked off.” Behrman Ibid; p. 10

This simply fails to understand the post-1917 period of Futurism, Constructivism, and other isms, in my view.

Obviously many bourgeois scholars are unable to adequately answer the above puzzles either. Perhaps that is because recently, so many have been generally taken up with a mythology deriving from Solomon Volkov.

“Cold War” pictures fabricated by Solomon Volkov’s “Testimony”

Today’s concert-goers are largely unaware of how deeply the partisan views of the “Cold War” against Soviet USSR up to 1953, penetrate any ‘purely’ musical interpretation of Shostakovich. Yet that ‘Cold War’ affects all narratives of Shostakovich, whether in scholarly works or novels.

For example, in reviewing a recently acclaimed novel by Julian Barnes, the music scholar Richard Tarushkin wrote:

“Mr. Barnes evidently wanted to capitalize on the interest that frenzied debate has drummed up in his subject and to claim implicitly to have settled the issues concerning the composer’s relationship with Soviet power, which scholars continue to dispute. . .

Mr. Barnes’s view of Shostakovich conforms in every detail to the sentimental Cold War fable of a passive, pathetic yet saintly figure buffeted by an obtuse, implacable force. . . These are the naïve assumptions of pop Romanticism.

The sources on which Mr. Barnes most conspicuously relies are the two canonical texts of the Shostakovich wars. One is “Testimony,” a best-seller that appeared in 1979 whose subtitle is “The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich as Related to and Edited by Solomon Volkov”; the other is the invaluable “Shostakovich: A Life Remembered” (1994) by Elizabeth Wilson.”

Richard Taruskin; “Was Shostakovich a Martyr? Or Is That Just Fiction?” New York Times; Aug. 26, 2016

This ‘Cold War’ attitude also affects music professionals. The gifted conductor Michael Sanderling for example, prior to his debut with the Berlin Symphony said in an interview with Emmanuel Pahud (First Flute) that the 7th Symphony (‘The Leningrad’) reflected the pain of the prior years of unjust imprisonments (See Digital concert Hall interview June 1 2019) . Sanderling offered for this speculation, the reasoning that after all “Shostakovich had produced the 7th Symphony in just 6 weeks”.

Naturally any composer brings to bear on a new piece his or her entire prior experience. And it may have taken time to percolate, and then get shown down on paper rapidly. However, Sanderling minimises just how fast Shostakovich wrote – in general. More specifically in the 7th, Sanderling also minimises both the time, and the emotive power of being in Leningrad during the war and the start of the siege. Elisabeth Wilson informs us that:

“The outbreak of the war found Shostakovich examining the graduation composition students at the Leningrad Conservatoire. His immediate preoccupation was to be of use to his country, but his poor eyesight prevented him from enlisting in any kind of active service or home guard. Nevertheless he did his stint as an auxiliary of the Fire brigade. . .

In early July. . . he made arrangements of songs for the concert brigades to perform at the Front. He was then able to settle down to write his 7th Symphony. The massive first movement was written in less than 6 weeks, the next two movements in under three weeks. Shostakovich was evacuated from Leningrad with his family on 1 October, he took with three completed movements of the 7th Symphony. . . .

Nikolai Sokolov describes the first days in Kuibshev. . . Once I asked Mitya what stopped him from completing his 7th Symphony. He replied: “You know, as soon as I got on that train, something snapped inside me. . . I can’t compose just now, knowing how many people are losing their lives. . .” But as soon as the news came through that the Fascists had been smashed outside Mosocw, he sat down to compose in a burst of energy and excitement. He finished the Symphony in something less than two weeks”.

Wilson Ibid; p.148, 154

Almost needless to say, but Sanderling led the Berlin Philharmonic astonishingly and wonderfully. But I did listen very hard for the footfall of the Yezhovschina. I must say I failed to detect it. Instead I heard the encirclement, fear, worry, and then determination to break through, and then moves to the final battle and victory. More or less as Shostakovich describes it himself. Naturally I plead guilty to being swayed by the title ‘The Leningrad” and the dates of the composition, and a knowledge of its composition circumstances. But only as guilty, as I fear Sanderling is – for his reading of Volkov’s “Memoirs”.

That partisan ‘Cold War” narrative of the musicologist – Solomon Volkov – has coloured all discussions of Shostakovich.

Volkov claimed his book was composed in frank interviews with Shostakovich. He alleges that Shostakovich was attacked by Stalin, and fought back with coded passages in his music. These were invisible to the casual listener – or to Stalin – it seems. For Volkov the ‘real’ Shostakovich was a hidden anti-Stalin dissident, a rabidly anti-communist.

Such allegations started the modern so-called “Shostakovich Wars”. However they were exposed as a fabrication:

“Mr. Volkov’s book . . . has been exposed as a mixture of recycled material that Shostakovich had approved for republication and fabrications that were inserted after his death. . .

Mr. Barnes has his hackneyed Shostakovich wonder whether Stalin had not only ordered up the editorial that attacked his opera but also had “perhaps even written it himself.” Nobody thought that in Russia in 1936: It was Mr. Volkov who raised the possibility for gullible Westerners in “Testimony.” But now we know who wrote it: a terrified former Yiddish writer named David Zaslavsky, who had become one of Stalin’s most reliable literary hit men. ”

Richard Taruskin; “Was Shostakovich a Martyr? Or Is That Just Fiction?” New York Times; Aug. 26, 2016

Whether it was Zalavsky, or Platon Krezhentsev will be discussed below. The point is that it is most unlikely to have been Stalin.

Volkov believes Shostakovich’s ‘real feelings’ about the USSR do not lie in either the famous 5th Symphony (‘A Soviet Artists response to just criticism’) or the Leningrad 7th symphony. For Volkov the ‘real’ Shostakovich resides more in the 10th Symphony with an alleged anti-Stalin theme; or in the Quartets, or in the ‘Babi Yar’ 13th symphony.

But other musicologists and art historians of Russia, probably the majority, are not entirely convinced:

“Was Shostakovich a “loyal son” of the Communist Party, as Pravda claimed on the composer’s death in August 1975? Was he a coward and reluctant collaborator, forced to survive by making political compromises? Or was he a secret dissident, a heroic teller of the truth through art, a voice of moral protest and dissent? This is how he was portrayed in ‘Testimony’, controversially presented to the world as “The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich” . . . in 1979.”

Orlando Figes; “The Truth About Shostakovich”; New York Review Books, June 10, 2004

One school of musicologists accepts the Volkov ‘Testimony’. For example Ian Macdonald (author of “The New Shostakovich”; London 1990) and the team of Allan Ho and Dmitry Feofanov (authors of ”Shostakovich Reconsidered” London 1998).

But a large body of non-Marxist musicologists and Shostakovich scholars, challenge Volkov’s interpretations and his “facts” (Pauline Fairclough; “Facts, Fantasies, And Fictions: Recent Shostakovich Studies”; Music & Letters, Vol. 86 No. 3; 452-460). Another leading Shostakovich scholar – David Fanning – baldly summarises:

“The fraudulence of Testimony is documented by Laurel Fay, ‘Shostakovich versus Volkov: whose Testimony? Russian Review 39 (1980), 484-93.”

David Fanning; “Talking about eggs: musicology and Shostakovich”; in Ed David Fanning; “Shostakovich Studies”; Cambridge 2009; p.4

Volkov mischaracterises several passages taken from prior published work in Soviet interviews with Shostakovich, as his own private interviews with a dying Shostakovich. Shostakovich’s widow and some of his friends challenged these as falsified. It is symptomatic that Volkov refused to allow his manuscript and notes any independent review. He now claims these are all ‘lost’.

In retrospect even the timing of the Volkov “Memoirs” was suspicious.

“The book appeared at a new height of the cold war, shortly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, when the bankruptcy of the Brezhnevite regime was highlighted by a series of highly publicized defections to the West. For certain Western readers the “true Shostakovich” that was revealed appeared as a fallen hero of the moral crusade against the Soviet Union.”

Orlando Figes; “The Truth About Shostakovich”; New York Review Books, June 10, 2004

But virtually single-handedly, the Volkov “Memoirs” guided the critical interpretation for audiences hearing his works. Every commentator at Shostakovich concerts – whether the BBC, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, NPR in the USA etc – now asserts that a frightened Shostakovich resorted to musical innuendo.

Some authors simply weave quite un-warranted innuendos. As for example Wendy Lesser, in “Music for Silenced Voices”, which was judged the “best music book of the Financial Times for 2011”. On the 7th Leningrad Symphony Wendy Lesser drops this little bomb:

“His mother, sister and nephew were finally evacuated from Leningrad to Kuibysehev during the early rehearsals of the 7th Symphony. . . Nor did he, (or anyone else, as far as I know) ever voice the suspicion that these relatives had been held hostage until he had had produced the requisite masterpiece. The flow of power and privilege and disaster and deprivation was too erratic, in the wartime Soviet Union, for such calculation to seem likely.”

Wendy Lesser; “Music for Silenced Voices – Shostakovich and his 15 Quartets”; New Haven; 2011; p. 49

But trust Wendy Lesser – to do exactly that – to make such ‘calculation’. Lesser, far from any war – let alone the engineered thrust of Hitler’s against the USSR – refuses to try to calculate the difficulties of the resistance in the USSR.

As Paul Mitchison drily puts it Volkov had wrought a perceptual change in Shostakovich’s image.

“Most audiences today listen to Shostakovich through Volkov’s ears. It is a remarkable feat . . . Indeed, at the time of his death in 1975, Dmitri Shostakovich was widely considered, in the words of his Pravda obituary, a “faithful son of the Communist Party.” He was Soviet Russia’s most decorated composer, and his popular symphonies often came pre-packaged with dedications to make even the most hardened Communist bureaucrat smile: “October,” “The First of May,” “The Year 1905,” “The Year 1917.”

Genuine dissidents such as Solzhenitsyn and Lydia Chukovskaya considered Shostakovich a coward and a villain. Shostakovich returned the compliment, allowing his signature to appear beneath a published denunciation of Andrei Sakharov. He had to be convinced not to sign a letter supporting the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia.

But twenty-five years ago, Solomon Volkov single-handedly destroyed this popular understanding of Shostakovich by publishing a manuscript that he alleged was the composer’s memoirs, dictated to Volkov as a young Soviet journalist.

‘Testimony’, as the book was titled, was explosive. In its pages, Shostakovich was revealed to be a bitter opponent of Soviet power who tried to express his resistance in music.

“The majority of my symphonies are tombstones,” he allegedly told Volkov. “Hitler is a criminal, that’s clear, but so is Stalin…. That is what all my symphonies… are about.”

Testimony transformed Shostakovich’s reputation in two ways. No longer considered a loyal servant of Soviet power, Shostakovich was increasingly understood, in one popular phrase, as a “secret dissident.” His music, meanwhile, was scoured for evidence of this dissidence, which was held to be the music’s “true” meaning.

There was just one problem: Testimony was not the document Volkov claimed it was.”

Paul Mitchinson; May 3, 2004; ‘The Nation’ (Vol. 278, Issue 17)

Volkov’s picture is undoubtedly falsified. W.B.Bland used him as a key source, but despite that Bland’s analysis largely holds up in my view. Largely, but not completely in my view. With newer published data, Bland’s narrative requires amendment.

Nonetheless perhaps Volkov does capture some grains of Shostakovich’s opportunism and his ‘play of both sides’ of the fence. Ian Macdonald highlights this (Review: Laurel E. Fay’s “Shostakovich: A Life”- A Review;).

A Further note on Sources

Both pro-Volkov and anti-Volkov schools line up an impressive array of musicologists and ‘witnesses’ to buttress their opinions. But interestingly, both schools frequently cited from the more ‘neutral’ biography of Elizabeth Wilson (“Shostakovich A Life Remembered”; London 1994). I take this as an anchor for many details. *In addition the letters of Shostakovich to his ‘secretary’, confident and friend – Isaak Glikman throw added light. (“Story of a friend. The Letters of Dmitry Shostakovich to Isaac Glikman 1941-1975”; Cornell, 20111*)

But in addition I find it strange that most literature takes no account of the many interviews that he gave in his own lifetime. This was collected in the volume “Dmitry Shostakovich: About himself and His Times”; Progress Publishers Moscow; 1980“. No doubt these are largely ignored, as they are simply dismissed as irrelevant dating from the revisionist USSR. There are places in the text that do appear to be from a propagandist rather than from Shostakovich himself. For example in a passage of a sudden paean of praise for Brezhnev from around 1970. There are also however meaningful sections including thoughts on old and modern composers of considerable interest. Where appropriate it will be referenced in the text.

Can Shostakovich’s career be summarised briefly? Before delving into details, I offer a working hypothesis – to be disproved or proven over the course of this article.

A life summary of Shostakovich

To reiterate the obvious, it is unlikely that we shall ever be certain if Shostakovich was a communist. Moreover he was an extremely complex man. Anyone capable of his compositions had to be so. But it is much easier to say that by the end of his life, he had not been a consistently, committed communist. I believe his career followed to some degree, this path:

(i) Shostakovich started out as an aspiring Bolshevik. Many have recalled that his family had helped various revolutionaries. He may have heard Lenin talk at a famous speech on Lenin’s return to exile to take command of the revolution, when he was a child.

(ii) Even during his studies, which began on entry to the St Petersburg Conservatory at the age of 13 years, he achieved quick success. He was enormously gifted which struck other musicians immediately. Then the famous German conductor Bruno Walter on a conducting tour in the USSR, met and heard him play his own Symphony No. 1. Walter premiered it in Berlin, making Shostakovich an international name in music (Schwartz Ibid p. 32). His subsequent work turned overtly towards proletarian societies of music and drama such as ‘Leningrad Theatre of Working Youth’ (TRAM).

(iii) But even in his early work he was attacked by ultra-leftists of the Proletkult and RAPM. These continued up to the Pravda attack of 1936.

(iv) His opera Lady Macbeth of Mtensk, in 1934 was initially very popular in the USSR. However it led to sharp criticism. I believe that he did accept this criticism – going on to compose his much admired 5th Symphony. The alternative hypothesis offered by bourgeois scholars, is that he disguised his real views and only pretended to heed criticism. For what it is worth, I will argue that his contrition was genuine at this stage. I think he was still trying to find his own style at this stage.

(v) Up till 1945, he remained interested in, and succeeded in producing socially relevant music. Hence the success of his 7th Symphony – the Leningrad – composed and performed in war-time Leningrad.

(vi) Like many innovative musicians (including J.S.Bach, Beethoven and innumerable others) he remained interested musically in finding new ways to express musical thoughts. He was simply not content to stay in prior moulds. This undoubtedly led him into conflicts with some ex-RAPM musicologists and musicians. And in addition, some of his musical experiments were not to the taste of CPSU(B) party leaders.

(vii) He continued to make public music that gained him public audiences. But he had also started writing a more private set of music mainly in his string quartets. In these he allowed himself to be freer both in his musical form and content. I believe that he had become by 1945 soured and increasingly alienated by the revisionist led Yezhovschina. Marxist-Leninists hold that Yezhov carried out a terrible miscarriage of justice in order to alienate workers and intelligentsia from the party. If so why should it be strange that Shostakovich saw that miscarriage? Possibly by then, he already tempered his initial enthusiastic leftism. Increasingly he developed a ‘public face’ and a ‘private’ one. In the latter he pursued internally his own musical path.

(viii) But he was still composing for a wider audience. By the time of the famous 1948 critique by A.A.Zhdanov on formalism, he was still in the USSR publicly acknowledged as the leading composer. That criticism was not followed by a sustained official ban. Upon appeal to Stalin about an unofficial ban, Stalin over-turned the ban. What lay behind the attack on formalism? It came in 1948 – at a time when the USSR was being forced into an isolationism. The USSR was being forced behind the ‘Iron Curtain” of Winston Churchill‘s making. Even immediately after his subsequent criticism in 1948 – in his open comments, Shostakovich remained a sharp critic of poorly performed music in the USSR, and politically openly backward musical content. He was asked by Stalin to represent the USSR musically at New York.

(ix) During N. Khruschev’s period of rule he joined the Communist Party. Now it seemed as if he had no choice in the matter and he was forced to join. *Glikman’s account of Shostakovich’s anguish is convincing of this.* There are also some comments by his widow that he was somehow forced into becoming a member.By now he was even more openly praised, and he was enjoying the fruits of recognition as a great artist. At this stage he appears to have acquiesced to Khruschev’s revisionist actions including invasion of Czechoslovakia. Ultimately by then, he had become an anti-Marxist-Leninist in his political actions. How much he had any choice in these decisions remains unclear. I suspect he had no effective choice.

(x) To a large extent he retained even then, enough musical independence to continue to produce some searing and meaningful music.

(xi) His work remains of considerable interest to the world’s working and toiling people. This includes his chamber works. I believe they are amongst the most important life enhancing musical works available to the world’s workers and toilers.

The overall plan of this article is as follows:

I believe there are three significant clues that can help to solve the Shostakovich puzzles.

One is the history of hidden revisionism in the USSR, which enabled ultra-leftists in the Arts to find niches such as within Proletkult up till 1920; and then in RAPM up till about 1934; and then within Agitprop. The name of Platon Krezhentsev is not well known to Marxist-Leninists, but is familiar to musicologists. His role was integral to the attacks on the Shostakovich opera ‘Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk’.

Second was the difficulty of actually finding a new dialectical balance between the form and content of a new Socialist Realist revolutionary classical music in the USSR.

Thirdly the external threats to the USSR in post-war USSR of 1945 onwards.

I endeavour to try to unlock the puzzles with these three keys.

To tackle these puzzles, first I discuss purely theoretical frameworks. These include some of the principles of socialist art theory. When distorted a range of right deviations and ultra-leftist deviations in the arts in the USSR post-1917 resulted.

This is followed by a chronological narrative of art history from 1917 to 1932. Regrettably, it has to follow the in-fighting between various art movements in the early Bolshevik USSR. In essence, this section describes the art movements of the period following the 1917 revolution. There were departures from socialist principles, as the conflicts on art raged between ultra-leftists of Proletkult and RAPM and the Marxist-Leninists. Initially the Bolshevik line was held by Lenin, and then later on by Stalin. In between, as revisionists had held onto positions in the arts, an uncertain period spawned major ideological uncertainty.

Only having placed Soviet music into a context, can we then follow Shostakovich’s career. This takes us from his early career up to the 1948 Zhdanov speech.

2. Development of music, and the balance of content and form in art

The origins of music

Music began as part of human communications in relation to wresting a livelihood from the natural world. In 1844 Karl Marx explicitly linked its essence and coming into being, to a social and “humanized nature”.

As he put it music is of no meaning to an “unmusical ear.” The “musical ear” is “either cultivated or brought into being”. Marx also understands the “forming of the five senses as a labour of the entire history of the world”:

“let us look at this in its subjective aspect. Just as only music awakens in man the sense of music, and just as the most beautiful music has no sense for the unmusical ear – is [no] object for it, because my object can only be the confirmation of one of my essential powers, therefore can only exist for me insofar as my essential power exists for itself as a subjective capacity because the meaning of an object for me goes only so far as my sense goes (has only a meaning for a sense corresponding to that object) – for this reason the senses of the social man differ from those of the non-social man. Only through the objectively unfolded richness of man’s essential being is the richness of subjective human sensibility (a musical ear, an eye for beauty of form – in short, senses capable of human gratification, senses affirming themselves as essential powers of man) either cultivated or brought into being. For not only the five senses but also the so-called mental senses, the practical senses (will, love, etc.), in a word, human sense, the human nature of the senses, comes to be by virtue of its object, by virtue of humanized nature. The forming of the five senses is a labour of the entire history of the world down to the present. The sense caught up in crude practical need has only a restricted sense.

For the starving man, it is not the human form of food that exists, but only its abstract existence as food. It could just as well be there in its crudest form, and it would be impossible to say wherein this feeding activity differs from that of animals. The care-burdened, poverty-stricken man has no sense for the finest play; the dealer in minerals sees only the commercial value but not the beauty and the specific character of the mineral: he has no mineralogical sense. Thus, the objectification of the human

essence, both both in its theoretical and practical aspects, is required to make man’s sense human, as well as to create the human sense corresponding to the entire wealth of human and natural substance.”

Karl Marx; Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844”; April and August 1844; at MIA

A link to labour as such was made explicit by Frederick Engels. He later laid out how the likely intermediary of the hand and labour – created the need to vocalise. It was labour that developed the need “of something to say to one another”:

“the development of labour necessarily helped to bring the members of society closer together by multiplying cases of mutual support, joint activity, and by making clear the advantage of this joint activity to each individual. In short, men in the making arrived at the point where they had something to say to one another. The need led to the creation of its organ; the undeveloped larynx of the ape was slowly but surely transformed by means of gradually increased modulation, and the organs of the mouth gradually learned to pronounce one articulate letter after another.”

Frederick Engels; “IX The Part played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man

1876”; Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1934; as part of Dialectics of Nature. At: MIA.

This “social need” of the hand – “a product of labour” developed a potential for many functions. It became over time the expert means of developing the playing of instruments, but also to the composed ‘music of a Paganini”:

“Thus the hand is not only the organ of labour, it is also the product of labour. Only by labour, by adaptation to ever new operations, through the inheritance of muscles, ligaments, and, over longer periods of time, bones that had undergone special development and the ever-renewed employment of this inherited finesse in new, more and more complicated operations, have given the human hand the high degree of perfection required to conjure into being the pictures of a Raphael, the statues of a Thorwaldsen, the music of a Paganini.”

Frederick Engels; “The Part played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man 1876”; Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1934; as part of Dialectics of Nature; at: MIA

The Marxist scholar of poetry – George Thomson extrapolated Engels’s sequence to the dance. Thomson explicitly notes the role of music in relation to the earliest forms of labour:

“As human skill improved, the vocal accompaniment ceased to be a physical necessity. The workers became capable of working individually. But the collective apparatus did not disappear. It survived in the form of a rehearsal, which they performed before beginning the real task – a dance in which they reproduced the collective, coordinated movements previously inseparable from the task itself. This is the mimetic dance as still practised by savages today.”

George Thomson; “Marxism and Poetry “; Lawrence & Wishart London nd circa 1949; p. 9

As Thomson goes on to describe, the separation of the voice from instrumental music followed:

“The three arts of dancing, music and poetry began as one. Their source was the rhythmical movement of human bodies engaged in collective labour. This movement had two components, corporal and oral. The first was the germ of dancing, the second of language. Starting from inarticulate cries designed to mark the rhythm, language was differentiated into poetical speech and common speech. Discarded by the voice and reproduced by percussion with the tools, the inarticulate cries became the nucleus of instrumental music.”

Thomson Ibid; p.19

This marked the likely start point of a long history of developing instrumental music.

This new art form of music – and especially in its full classical form of the symphony – is the most difficult of the arts to relate to. For that reason, interpretations of music, can be contentious.

Form and content of art in general

Many art theorists drew attention to two primary components of art of all types. These are content and form. Marxists-Leninists also recognise this distinction:

“The content of a work of art is the character imparted to its subject. by the artist, a character which reflects the artist’s intellectual and emotional – in short, psychological – attitude towards his subject.”

“Theses on Art”; London 1972 by the MLOB and League of Socialist Art’; London; at Alliance ML.

“The form of a work of art is the manner in which an artist constructs his work of art in order to express its content. On the form of a work of art depends its capacity to communicate its content to consumers.

The form of a work of art is described in terms of the degree to which it truthfully reflects its subject, that is, in terms of the degree of its realism. The further the form of a work of art departs from realism, the nearer it approaches to abstraction, in which the form of a work of art reflects its subject in no discernible way. An abstract painting is composed of shapes and colours, which reflect reality in no discernible way, an abstract poem is composed of sounds without discernible meaning, and so on.“

“Theses on Art”; London 1972 by the MLOB Ibid.At: Alliance ML

Rupture of any unity between content and form – is what can make a particular work of art fail to achieve the highest level:

“The subject alone does not determine a particular form; but content and form or meaning and form, are closely bound together in dialectical interaction.”

Ernst Fischer,“The Necessity of Art – A Marxist Approach”; 1959 ; Tr Anna Bostock London 1981; p.131

What does any such rupture between form and content look like, or sound like?

Content – or as Fischer expresses it ‘meaning’- is itself made up of two aspects:

“The content of a work of art comprises two inter-related components:

1) the reflective content, and

2) the effective content.”

“Theses on Art”; London 1972 by the MLOB Ibid.At: Alliance ML

How do these differ? The reflective content reflects the artist’s self-view of their own life experience:

“The reflective content of a work of art is the reflection in this work of art of the artist’s world outlook – itself the subjective expression of his/her whole life experience. This world outlook is essentially that of the social class to which the artist belongs or with which he identifies his interests.“

“Theses on Art”; London 1972 by the MLOB Ibid.At Alliance ML

The effective content is what the end objective result achieves in its social or political effect:

“The effective content of a work of art consists of the particular thoughts and feelings, which the artist endeavours to create in the minds of consumers through the work of art concerned. The effective content of a work of art is described in terms of the social effects which these thoughts and feelings tend, objectively, to produce: as progressive . . . or as reactionary . . .”

MLOB Ibid

These two elements or components interact. If the artist conciously strives to connect the two elements – at its best this can heighten the mood that is achieved in the audience:

“The inter-relation between the reflective and effective components of the content of a work of art is thus a variable one, dependent on the stage of the development of the society in which the work of art is produced.

The more conscious an artist is of the class basis of the reflective content of his art and of the social effects of its effective content, the closer will the two components of the content of his art be integrated, and the more will the reflective content reinforce the effective content – the more powerful will be the thoughts and feelings created by his art.”

“Theses on Art”; 1972; the MLOB Ibid.

Ideally the form chosen is one that does not distract from the elements of content, but if anything enhances it.

Formalism in art, is usually meant to convey an art that is ‘distracting’, ‘incoherent’, ‘abstract’, or ‘difficult’. It is also a tendency to focus more exclusively on the form, and a tendency to disregard the content. The MLOB called formalism an “abdication” from content:

“abdication from the need to develop content through concentration on questions of form, not to illuminate and express an effective content, but for their own sake.”

Introduction; “Theses on Art”; 1972; Ibid; Alliance ML

Taken together, there are several potential break-points, at which a work of art may fail to achieve a social impact. Even when a social impact is actually desired by the artist.

Deviations from Marxism in politics

Revisionism is a perversion of Marxism-Leninism to serve the interests of the capitalist class.

It can take two main forms, a right deviation or a left deviation.

In general right wing deviations from Marxism-Leninism are relatively easy for the committed proletarian worker to recognise and expose. But this is often not so easy for a deviation that dresses itself as being a ‘left-wing’ movement.

Ultra-leftism is a political stance which generally places the communist movement far ahead of the political understanding of the working class. Indeed so far that it cannot help to move workers politics forward. It makes demands that either not understood by workers themselves as reasonable, or are simply not attainable at that time – or often both. Furthermore it often levels quite personal attacks at leaders of non-communist organisations including trade unions or reformist parties. When this takes place, it will usually alienate the workers from the positions that communists try to win the workers to.

Ultra-leftism was exposed by Marx and Engels in their battles with the anarchists of Mikhail Bakunin who sabotaged the First International. Engels showed how this failed Spanish workers struggles. Engels uses the phrase “ultra-revolutionary“ rather than ultra-leftism. Bakunin’s allies did this by calling prematurely for ‘Revolution Now!’ . To be concrete, as opposed to helping the workers take any interim steps to get to the point where revolution was feasible. The Bakuninists argued instead that “no part should be taken in a revolution that did not have as its aim the immediate and complete emancipation of the working class”. The fuller context in this example is given as follows:

“Mikhail Bakunin’s secret Alliance has revealed to the working world the underhand activities, the dirty tricks and phrase-mongery by which the proletarian movement was to be placed at the service of the inflated ambition and selfish ends of a few misunderstood geniuses. . . they put into practice. . . ultra-revolutionary phrases about anarchy and autonomy, about the abolition of all authority, especially that of the state, and the immediate and complete emancipation of the workers. . . Spain is such a backward country industrially that there can be no question there of immediate complete emancipation of the working class. Spain will first have to pass through various preliminary stages of development and remove quite a number of obstacles from its path. . . But this chance could be taken only if the Spanish working class played an active political role. . . The members of the Alliance on the other hand had been preaching for years that no part should be taken in a revolution that did not have as its aim the immediate and complete emancipation of the working class, that political action of any kind implied recognition of the State, which was the root of all evil, and that therefore participation in any form of elections was a crime worthy of death.”

Frederick Engels; “The Bakuninists at Work- An account of the Spanish revolt in the summer of 1873”; from: “K. Marx, F. Engels, Revolution in Spain”, Lawrence & Wishart, London, 1939; at MIA:

Lenin, also identified the same major danger for the working class that lies in calls for a “revolutionary purity”. Lenin in 1918 pointed out a need instead for a step-wise progress in political demands that fit particular moments in time, that relate to that moment:

‘It is not enough to be a revolutionary and an adherent of socialism or a Communist in general. You must be able at each particular moment to find the particular link in the chain which you must grasp with all your might in order to hold the whole chain and to prepare firmly for the transition to the next link; the order of the links, their form, the manner in which they are linked together, the way they differ from each other in the historical chain of events, are not as simple and not as meaningless as those in an ordinary chain made by a smith.”

V.I. Lenin; “The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government”; The Development of Soviet Organisation”; March-April 1918; Collected Works, Moscow, 1972 Volume 27, pages 235-77 at MIA

In his most famous work on the question of “ultra-leftism”, Lenin was mainly directed against those eschewing parliamentary or trade union means of work. These ultra-lefts ended up arguing for ‘revolution now’. But argued this at times when the working class was not yet at the point of being able (whether mentally or pragmatically and practically) to reject bourgeois democratic means of struggle. The class had not reached that level of political understanding. For example Lenin attacked the German Lefts, who:

“Contrary to the opinion of such prominent political leaders as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, the German “Lefts” considered parliamentarism to be ‘politically obsolete’ as far back as January 1919. It is well known that the ‘Lefts’ were mistaken”.

V. I. Lenin: “Left-wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder”, in: “Selected Works”., Volume 10; London; 1946; p. 98

Lenin always stressed the need for working with “real humans” in mind and not an “abstract” notion of “human material“:

“We can (and must) begin to build socialism, not with abstract human material, or with human material specially prepared by us, but with the human material bequeathed to us by capitalism. True, that is no easy matter, but no other approach to this task is serious enough to warrant discussion.

. . . the revolutionary but imprudent Left Communists stand by, crying out “the masses”, “the masses!” but refusing to work within the trade unions, on the pretext that they are “reactionary”. . .

‘It would be hard to imagine any greater ineptitude or greater harm to the revolution than that caused by the “Left” revolutionaries! Why, if we in Russia today, after two and a half years of unprecedented victories over the bourgeoisie of Russia and the Entente, were to make “recognition of the dictatorship” a condition of trade union membership, we would be doing a very foolish thing, damaging our influence among the masses, and helping the Mensheviks. The task devolving on Communists is to convince the backward elements, to work among them, and not to fence themselves off from them with artificial and childishly “Left” slogans.”

V.I.Lenin; “Should Revolutionaries Work in Reactionary Trade Unions?“; in ““Left-Wing” Communism: an Infantile Disorder”; April–May 1920; Collected Works, Volume 31, pp. 17–118; and at MIA

Ultra-leftism alienates the working class and impedes their movement towards the communists. Yet precisely because it poses as being so “revolutionary”, it is more difficult to un-mask than right deviations.

Right and Left Deviations from Marxist views in art and aesthetic theory

Revisionism is a philosophy found within working class movements which distorts Marxism-Leninism. The ultimate effect – whether intentional or unintentional – is to serve the interests of the capitalist class. Just as in the broader political arena, it can manifest itself in the arts.

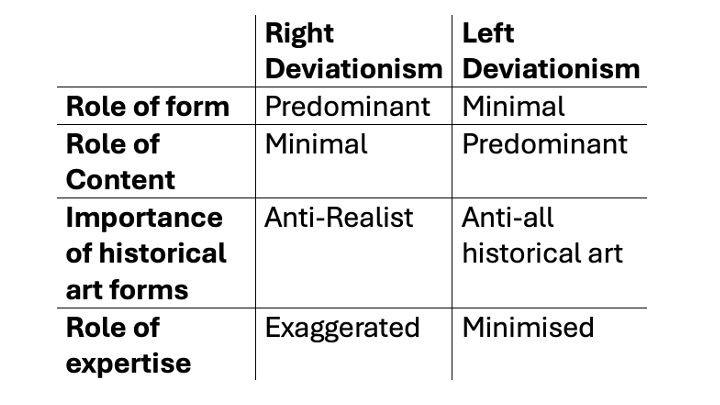

In the art schools of the post-1917 Russia and the USSR were several variants of either rightist or of ultra-leftist type. The following broad taxonomy is not given in abstract. It comes from the history of the art movements in the post-1917 USSR. Before looking at the politics of the period however, I believe a characterisation of how the ideology played out in art terms may be of help.

One particular way in which such deviations are shaped, is by disrupting the essential unity of form and content. As we noted above:

“The subject alone does not determine a particular form; but content and form or meaning and form, are closely bound together in dialectical interaction.”

Ernst Fischer, “The Necessity of Art – A Marxist Approach” 1959 ; Tr Anna Bostock London 1981; p.131

Engels talks about this fusion in a very specific manner, to Ferdinand Lassalle. This is Engels’ advice on Lassalle’s drama “Franz von Sicklingen”. He advised judicious cutting to render it suitable for the stage which does not respond well to “long monologues”. This would restore a fusion of content and form:

“The idea content must, of course as a result suffer, but this is unavoidable. The full fusion of the greater depth of thought, of the conscious historical content, … with Shakespearian liveliness and fullness of treatment. . . is the future of drama.”

Frederick Engels Letter to Lassalle May 18, 1859; in “Marx and Engels on Art and Literature” Moscow 1976; p.103.

More generally, deviations from the unity, which rupture the “bounded together-ness”of form and content – can take either a right or ultra-left style or aspects. These are quite various.

For example, one major right deviation is to stress only the form.

When for example, artists adopt a position of ‘art for arts’ sake’ . They repudiate content in the art basing themselves on “form” alone. Such artists are simply not interested in eliciting any response, actually their art does not aim at any effective content.

Often they may also argue that to overcome “bourgeois art” they must reject all prior, realist art:

“They hold that aesthetic questions – i.e. questions of quality in art – must be confined to questions of craftsmanship.

On the basis that art which directly serves the interests of the capitalist class is realist in form (as discussed above), they hold that “revolutionary art” must break with the “reactionary” heritage of realist art. . .

. . . They therefore repudiate content more or less completely, take their stand on the slogan “Art for art’s sake” (which rejects the conception of social content in art) and base their art purely on form: on abstract or semi-abstract images. It is this repudiation of content and concentration on form that revolutionary Socialists call “formalism.”

Introduction to, and “Theses on Art”; London 1972 by the MLOB and League of Socialist Art’; London; at Alliance.

An exhalation and resurgence of tribal art forms, or Cycladic Greek early art – reflects this. Not that such art is poor by any means. But stripped of its context and re-presented as art for today – is a reactionary bow.

Right deviations in art may also stress “availability” of art – rather than content. Claims to be ‘socialist’, are replaced by relying on working class access to art:

“To the modern revisionists, the changed role of art in a socialist society means no more than the wider availability of art to the working people.

But, clearly, the interests of the working class and of socialism are not served by the wider availability, to the working people of art which serves the interests of the capitalist class – the class enemy of the working-class.

In fact, art which serves the interests of the capitalist class is widely available to the working people, within a capitalist society. A worker has little difficulty in obtaining access to the strip cartoons in the “Daily Mirror”; he can watch “Coronation Street” on TV; he can listen to “pop” music almost throughout his spare time; he can visit a “working man’s club”; and watch strip-tease shows every week-end.”

“Theses On Art” From The League Of Socialist Artists; London UK, 1972; Ibid at Alliance ML

A different right danger in theories of art is to simply deny any need for any changes from previous art, or historical art. These proponents argue that it is perfectly all right to stay within the moulds of either old art forms, or old content – or both.

For Right proponents in art, the form – and sometimes even content – of art from prior social eras is perfectly fine. A modern day example of this is the Estonian composer Arvo Pårt. His music became overtly liturgical, and was a very conscious retreat from the post-1953 Khruschevian revisionist USSR:

“the conductor Neeme Järvi (said in an interview) . . . “Everything in Estonia was Shostakovich and Prokofiev. . . But then there was this strange music that was different from what others were doing, and it was from Estonia.” It wasn’t long before Pärt moved on from serialism, experimenting with a collage technique that mixed early music, like Gregorian chant, with modern dissonance. Eventually, with “Credo” in 1968, he took a turn for the overtly spiritual.”

Joshua Barone; “Arvo Pärt Reached Pop Star Status. Now He’s Ready to Rest.”; New York Times September 11, 2025.

Finally another rightist danger is to deny any need for any socialist aesthetics. Such is the case in the later work of Gyorgy Lukacs for example. As the ‘MLOB’ put it:

“Lukacs has been at pains to repudiate his earlier correct, not to say pioneering, work and is now performing yeoman service on behalf of the right-revisionist centre in Moscow. This he is doing by denying in general any validity whatever of aesthetics as a science – thereby negating both his own earlier work and the objective growth and subjective need by the class conscious revolutionary proletariat wherever it may arise, of an art and Literature fully capable of expressing the world view and historical destiny of the proletariat as the prime mover of the socialist revolution.”

Introduction; “Theses On Art” From The League Of Socialist Artists; London UK, 1972; Ibid At Alliance ML

Other attitudes characterise left deviations in art.

One rejects all prior historical artistic forms as completely irrelevant to the working class – not merely 18th-19th century realist. All prior art is to be rejected dismissed according to these ‘socialist’ artists. This simply extends what we saw in right trends to reject any ‘realist’ art. It extends this view to any previous historical art.

While it sounds ridiculous, this is in fact what a large contingent of artists proposed in the post-1917 revolutionary Russia.

Another form of ultra-leftism in art heavily prioritises content – over any consideration of form.

This presents art with only an effective progressive content, regardless of form. At its extreme, it simply states “this content here is socialist art because it states it is so”. But if the form does not help the viewer to understand the subjective content, then the art is useless in conveying any effective content.

A variant of this is insists that the sole reliance on a stated content extends to a rejection of any professional standards. Since these artists reject form, repeating “this content is socialist art” – this can be regardless of any form.

These errors tend towards a common failing in ultra-left, which is to blur distinctions between art and propaganda.

Another variant of ultra-leftism in music might be termed ‘dumbing down’. This argues that the working class cannot understand complex music, it must be made to be simpler. This has the effect of damping adapting to current standards.

In the 17th century J.S.Bach faced a variation of this. While Bach’s compositional skills became recognised widely and quickly, there was criticism in his own lifetime of an “over-complexity”. Or as a music critic Johann Adoplh Scheibe wrote “over-loading“:

“This great man would be the admiration of whole nations if he [his composition] had a more pleasing quality, and if he did not remove naturalness from his pieces by an unclear [schwülstiges] and incomprehensible [verworrenes] manner, and obscure their beauty by all-

too-great art. Because he judges according to his own fingers, his pieces are extremely difficult to play. He requires singers and instrumentalists to produce with their voices and instruments what he can play on the keyboard. This, however, is impossible. He uses conventional notes to express all the ornaments, all the small embellishments, and everything understood to fall under the method of playing. This not only removes the harmonic beauty, but also obscures the melody. [All voices have to work together and be equally difficult; no principal subject is recognizable.] . . . Over-loading has led both from the natural to the artificial and from the noble to the obscure. In both, one admires the difficult work and exceptional effort, which, however, is used in vain because it conflicts with Nature.”

Johann Adolph Scheibe; cited by Beverly Jerold; “The Bach-Scheibe Controversy: New Documentation”; Bach, 2011, Vol. 42, No. 1 (2011), pp. 1-45.

Bland points out that a key word here is to ‘suggest’ realism, and that a socialist realist work of art must not give the impression of being propaganda. Again this was also point made by Engels. As Engels expressed it in 1888, again to Margaret Harkness:

“The more the opinions of the author remain hidden, the better the work of art.”

Friedrich Engels: Letter to Margaret Harkness (April 1888); in: Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels: ‘On Literature and Art’; Moscow; 1976; p.91

To even more clearly explain to Margaret Harkness this distinction (between art and propaganda) Engels explicitly discusses Honore Balzac, who he prefers to Emile Zola. Despite that Zola was politically an engaged leftist and Balzac was a “Legitimist” or a supporter of the Bourbons overthrown in 1792). We will discuss later Engels’ view on “tendentiousness” in art.

Just as in general politics, it is more difficult to detect the various ‘ultra-left’ forms of revisionism in art – than it is to detect the right revisionisms. I try to boil down its differences from right deviation, in a simple table below. Perhaps too simple, since context is crucial. Nevertheless it may have some taxonomic use.

The problems of interpreting music

Finally a caution has to be sounded. The abstraction of music makes its interpretations often quite unclear and subjective. It is likely that for example, that J.S.Bach found that his Fugues were rather more difficult for audiences than his Masses.

Understanding the content of music – especially if it carries no libretto, or no title – is simply not as transparent as understanding a painted canvas. Granting a title or a hint of the inspirational source to music, helps elucidate the mental images evoked. The vivid example of Ludwig Beethoven illustrates this.

Even the ultra-leftists of movements such as RAPM conceded (finally) that Beethoven was of significance for proletarian audiences in the USSR. The ultra-leftists tolerated him largely based on Symphony no.3 (‘Eroica’). There Beethoven famously tore out his prior dedication to Napoleon Bonaparte after the latter declared himself ‘Emperor’.

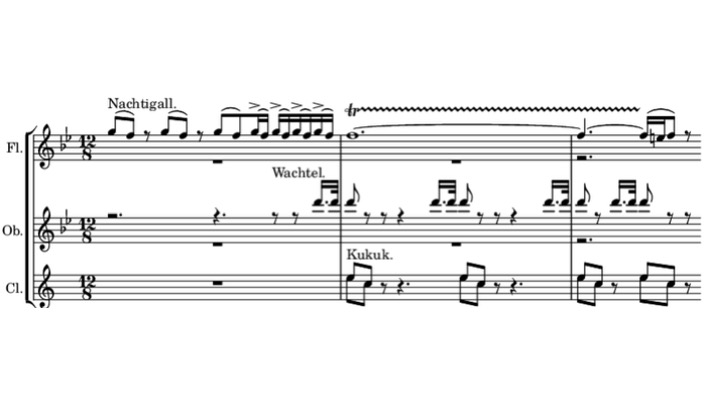

Yet Beethoven felt it necessary to use subtitles for some of his other symphonies as well. Perhaps a more vivd example of the felt need of even the maestro Beethoven for guides to guide listeners is the “Pastoral”. In that great Symphony No.6 of 1808, labels are given. Such as the first movement, “Awakening of cheerful feelings on arrival in the countryside“. Moreover even though he clearly voices sounds of birdsong in the second movement (“Scene by the brook“) – he felt it necessary to write in the score which instrument was playing which bird was singing (See below).

The Russian composer Nikolai Roslavetz – a “dedicated communist” – sarcastically dismissed the Ultra-leftists of RAPM – who only saw content as important. He put it this way:

“Roslavetz attacked the concept of “representational” music. Using his slogan, “Music is music, not ideology”. . . “If we cross out the title ‘Hymn of Thanksgiving’ in Beethoven’s Quartet Op. 132 and substitute ‘Festive Victory Celebration of the Red Army’ or ‘Opening of the Streetcar Line in Baku’—does this in any way change the content of the quartet?”

Boris Schwarz; “Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia: Enlarged Edition, 1917-1981”; p.37;

Roslavetz’s career was destroyed in return for his views, by the ultra-lefts of RAPM:

“Roslavetz was described as “the rotten product of bourgeois society” and the exponent of “petit- bourgeois reaction hiding behind leftist phraseology. . . Roslavetz suffered professional ostracism and eventual oblivion after 1930.”

Boris Schwarz; “Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia”; Ibid; p.31, 38

This quality of an ‘opacity’ in ‘pure’ music was recognised in the USSR at the highest levels of music appreciation and education in the USSR. For example, many adjudicators of the ‘Stalin Prize’ in music acknowledged this, during various heated pro and anti-Shostakovich discussions.

The anti-Shostakovich musicologist Alexander Borisovich Goldenweiser insisted that:

“calling a musical work formalist just because one doesn’t understand it, is not always correct.”

Marina Frolova-Walker; “Stalin’s Music Prize – Soviet Culture and Politics”; Yale New Haven; 2016; p.100;

The chair of the Prize Committee of the Stalin Prize (KSP) Moskvin rejecting anti-Shostakovich views, claimed that:

“Music is obscure.”

Marina Frolova-Walker; Ibid; p.98

Between the years 1940-1953 – one common criticism of Shostakovich was indeed of “formalism”. But many reputable Social Realists pushed back against this and insisted that his music was not ‘gloomy, difficult to understand” etc.

Even the anti-Shostakovich socialist realist writer Alexander Fedayev, defended Shostakovich’s work setting poems on the 1905 failed revolution (‘Ten Poems on texts by Revolutionary poets op 88”).

In fact Fedayev was a former RAPP leader:

“For his major film projects of the decade, was assigned successively the former RAPP

leader Aleksandr Fadeev (for Moscow in Time).”

Katerina Clark; “Moscow, the Fourth Rome. Stalinism, Cosmopolitanism, and the Evolution of Soviet Culture, 1931-1941”; Cambridge, Massachusetts ; 2011 “; p. 83.

The charge was raised of pessimism – and in truth – it was prompted by the historical truth of the failure of the 1905 revolution. Fedayev rejected this saying:

“I can’t see that listeners after hearing this piece, would descend into gloom and start crying over (1905) revolutions; failure. . . This is not at all formalist music. It is heroic music, music that makes you want to sing together with the choir.”

Marina Frolova-Walker; Ibid; p. 109

Vera Mukhina “The great sculptor” – whose Socialist Realist masterpiece is the ‘Collective meets the worker”, during a heated debate on whether the 8th Symphony was to be attacked, or if it should be awarded a prize praised it:

“In my opinion the 8th Symphony is not at all lower than the 7th. . . The impression is colossal. The 8th Symphony is a huge work. There might be drawbacks, but there are always drawbacks. The two marches are quite exceptional.”

Marina Frolova-Walker; Ibid; p. 94

Finally the composer Kablevsky explicitly made a link between “Soviet titles of compositions and their non-Soviet content“. to the “the RAPM times”:

“Already in 1934, Kabalevsky had pointed to the discrepancy between Soviet titles of musical compositions and their non-Soviet content. He maintained that Soviet composers had not yet found “expressive means corresponding to the topics selected, and that even the topics were not always thought out thoroughly”. Kabalevsky’s criticism was obviously aimed at the shift to Soviet thematics that became so widespread around 1930. In lieu of “content”, the composers simply attached a catchy title or a programme to their music. This, Kabalevsky felt, was a “remnant of the RAPM times … the distrust of purely instrumental music which allegedly was incapable of fully reflecting our Soviet reality”. And in a final blow at “concrete musical images”, Kabalevsky said, “It does not mean at all that Soviet music must ‘depict’ and ‘portray’ concrete facts and occurrences—things of which, perhaps, music is not even capable. We must keep in mind the concrete ideo-emotional basis of creativity.”

Kabalevsky expressed what was on the mind of many serious composers.

Shostakovich said it bluntly and rather ironically, “There was a time when the problem of content was simple: put in some verses, there’s content; no verses—formalism.”

Boris Schwarz; “Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia: Enlarged Edition, 1917-1981”; p.94

An introduction to the Formalism Debate of 1948

Before reverting to a chronological description, it is appropriate in this section on aesthetics, to skip ahead in time and introduce the 1948 debate on formalism. After all is said and done – what is formalism?

A.A.Zhdanov explicitly called Shostakovich a ‘formalist’:

“The names of the following comrades have been mentioned: Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Myaskovsky, Khachaturyan, Popov, Kabalevsky and Shebalin. . . (and) Shaporin.