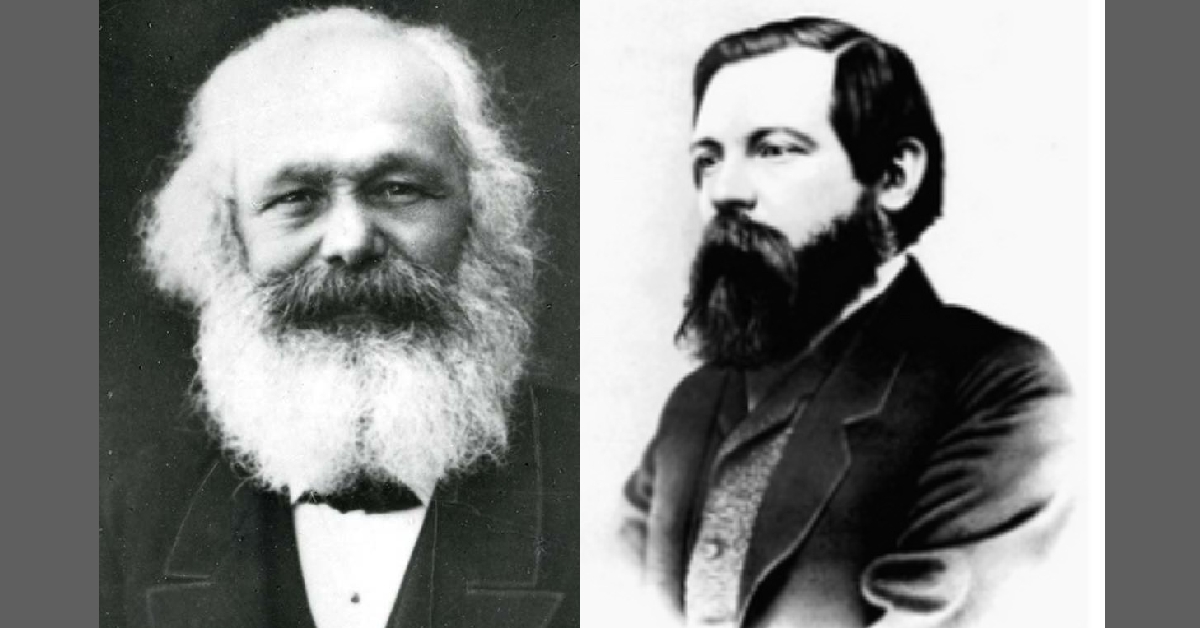

Views of Marx and Engels on Revolutionary Organisations

Views of Marx and Engels on Revolutionary Organisations

13 January 2026

1. Introduction

This article examines the changing views of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels on a worker’s party over time. These changes did not get “dreamed up”, but naturally arose from the course of the proletarian movement. As Marx put it:

“these (communist – ed) theoreticians… in the measure that history moves forward, and with it the struggle of the proletariat assumes clearer outlines, they no longer need to seek science in their minds; they have only to take note of what is happening before their eyes and to become its mouthpiece.”

Karl Marx; “The Poverty of Philosophy”; Chapter 2.1: The Metaphysics of Political Economy (The Method) at: MIA

The article is spurred by discussions on the Marx Mail forum list. Arguments were recently put there, suggesting that Lenin’s views on party contradicted those of Marx and Engels.

Since Marx and Engels did not have one single party that they worked with through their activist lives, it is not possible to point to just a single text of theirs in this regard – not even the ‘Communist Manifesto” alone. The only viable alternative is to review their activist history over the years.

As is well known, Lenin described a vanguard party concept which formed the policy of the Bolsheviks. Our views on this have been on record since 1973 (MLOB: “What is to be done now?” at MIA). While this is salted with 1970s-era revolutionary optimism, the paper in core stands the test of time.

In reality the argument that there are major differences between Marx-Engels and Lenin upon the party, is not novel. This is forthrightly declared and enshrined in Encyclopedia Britannica as follows:

“Marxism predicted a spontaneous revolution by the proletariat, but Leninism insisted on the need for leadership by a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries (such as Vladimir Lenin himself).”

The Editors; “How does Marxism differ from Leninism?” accessed 25 December, 2025; at: Britainnica

Attempts to divide Marx and Engels from each other are frequent and were discussed previously. But attempts to divide them both from Lenin are also frequent. Perhaps latching onto the enormous body of economic and historical materialist theory from Marx and Engels is more comfortable for some – than the insistent drive to organise in Lenin. For this article we will leave aside Stalin.

This discussion is of course far from ‘academic’ in today’s USA or any of the world’s countries. In the USA, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) hope to revitalize, or ‘ginger up’ the Democratic Party (DP), rather than creating a party outside of the DP. Some voices however, attack the DP as irretrievably penetrated and owned by the capitalist class and call for a new Leninist-type party. We believe this to be correct. Meanwhile, there is no large, avowedly proletarian party in the USA. The world’s toilers are facing an enormous crisis, and no large Marxist-Leninist party exists in any country. A discussion on the party is over-due.

The plan of this article

To show there is no major difference in the views of Marx and Engels versus Lenin, on the question of the need for a party of professional revolutionaries – necessitates many lengthy citations. We cover the field in the following plan:

First, we break down a frequently cited quotation from Engels used to support the old canard.

Secondly, we make general remarks about the different paths Marx and Engels faced.

Thirdly, we then mark a point in their path from where a clearly narrower path is taken. That break-point is the Paris Commune.

Fourthly, we pass to briefly review historical time-lines and the party formations used by Marx and Lenin.

Finally, we have a short conclusion.

2. Engels’s 1887 formulation

The old canard of claims that Marx and Engels did not support an organised party in the Leninist sense emphasises Engels advice to the American Socialist Labor Party in 1887:

“To bring about this result, the unification of the various independent bodies into one national Labor Army, with no matter how inadequate a provisional platform, provided it be a truly working class platform – that is the next great step to be accomplished in America. To effect this, and to make that platform worthy of the cause, the Socialist Labor Party can contribute a great deal, if they will only act in the same way as the European Socialists have acted at the time when they were but a small minority of the working class. That line of action was first laid down in the “Communist Manifesto” of 1847 in the following words:

“In what relation do the Communists stand to the proletarians as a whole?

The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties. They have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole. They do not set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement.”

The Communists are distinguished from the other working-class parties by this only:

1. In the national struggles of the proletarians of the different countries, they point out and bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality.

2. In the various stages of development which the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie has to pass through, they always and everywhere represent the interests of the movement as a whole.

Frederick Engels; “The Condition of the Working Class in England Preface to the American Edition; London, January 26, 1887; Volume 26 Moscow 1990; p.441; Also at: MIA

Canardists wish to imply that there is no distinction between the ‘party’ and the ‘class’. At least by the authority of Marx and Engels. It is true that in one snippet Engels does imply that there is no party aside from the whole proletariat, as here:

“The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties. They have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole.”

However, other parts of the quote suggest an approximation to Lenin’s later, more specified formulation of a “professional revolutionary”:

Firstly, the very next passage states characteristics of the Communists who are the ‘most advanced and resolute section of the working class parties’:

“The Communists, therefore, are on the one hand, practically, the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others…“

At: MIA

Secondly, this sub-group of the working class – the “most advanced and resolute Communists” – has acquired:

“theoretically the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march,”

At: MIA

But how did this sub-group of the class arrive at a “theoretical line” of the “line of march”?

Engels is clear that this is not by ‘inventing’ it, but presumably by studying and generalising – the ‘historical movement going on under our eyes”:

“The theoretical conclusions of the Communists are in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered by this or that would-be universal reformer.

They merely express, in general terms, actual relations springing from an existing class struggle, from a historical movement going on under our very eyes.”

Frederick Engels; “The Condition of the Working Class in England, Preface to the American Edition; London, January 26, 1887; Volume 26 Moscow 1990; p.441; Also at: MIA

Is this not already – without considering more data – coming very close if not identical to Lenin’s formulations?

Thirdly, another fundamental concept can be seen within this entire text. Without naming it as such, it expresses the need of a United Front. For the advanced section of workers – being the ‘Communists’ – has the “same common immediate aim as all other proletarian parties”. That includes at this stage the “formation of the proletariat into a class”:

“The immediate aim of the Communists is the same as that of all other proletarian parties: formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat.”

Frederick Engels; “The Condition of the Working Class in England Preface to the American Edition; London, January 26, 1887; Volume 26 Moscow 1990; p.441; At: MIA

This sense of a United Front recurs again and again in the work of Marx and Engels as we shall see. We submit that it is in this sense that Engels means that “The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties.” Engels sees the Communists as being in a united front of sorts – but maintaining its independence.

Finally, the proletarian class, says Engels, has not yet even fully formed by 1887. Thus, the Communists who aim at the “formation of the proletariat into a class”, of necessity, must be distinct from that class.

The earlier words:

“The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties. They have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole”…

… are intended we argue, to imply something quite different from that intended by today’s Canardists. The sense of Engels’s does not separate Marx and Engels from Lenin.

3. Marx and Engels had to chart a new path forward

Obviously Marx and Engels were in uncharted territory from the start. After all, the proletarian class had only recently been identified and defined as such – by themselves. Engels’s work on the working class of England was the first to place the working class at the center of the vast social changes taking place. As Engels wrote:

“The condition of the working-class is the real basis and point of departure of all social movements of the present because it is the highest and most unconcealed pinnacle of the social misery existing in our day. French and German working-class Communism are its direct, Fourierism and English Socialism, as well as the Communism of the German educated bourgeoisie, are its indirect products. A knowledge of proletarian conditions is absolutely necessary to be able to provide solid ground for socialist theories, on the one hand, and for judgments about their right to exist, on the other; and to put an end to all sentimental dreams and fancies pro and con. But proletarian conditions exist in their classical form, in their perfection, … particularly in England proper.”

Engels 1845; at MIA

Both Marx and Engels and the newly birthed working class itself, faced new challenges as the mass proletarian movement awoke to its own powers. As it did so, the class suffered several defeats – but they and the Communist theoreticians – also gained successes and clarity as to how to move out of defeat.

It was a process, but one in which Communists were consciously developing with the class: they were “theoreticians”:

“Just as the economists are the scientific representatives of the bourgeois class, so the Socialists and Communists are the theoreticians of the proletarian class. So long as the proletariat is not yet sufficiently developed to constitute itself as a class, and consequently so long as the struggle itself of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie has not yet assumed a political character, and the productive forces are not yet sufficiently developed in the bosom of the bourgeoisie itself to enable us to catch a glimpse of the material conditions necessary for the emancipation of the proletariat and for the formation of a new society, these theoreticians are merely utopians who, to meet the wants of the oppressed classes, improvise systems and go in search of a regenerating science. But in the measure that history moves forward, and with it the struggle of the proletariat assumes clearer outlines, they no longer need to seek science in their minds; they have only to take note of what is happening before their eyes and to become its mouthpiece. So long as they look for science and merely make systems, so long as they are at the beginning of the struggle, they see in poverty nothing but poverty, without seeing in it the revolutionary, subversive side, which will overthrow the old society. From this moment, science, which is a product of the historical movement, has associated itself consciously with it, has ceased to be doctrinaire and has become revolutionary.”

Karl Marx; “The Poverty of Philosophy”; Chapter 2.1: The Metaphysics of Political Economy (The Method) at MIA

We believe that Marx’s and Engels’s response to party formation can only be seen as reflecting this turbulent and difficult history. It evolved by the end of their organising lives into something coming close to Lenin’s later formulation. Over this period, the word ‘party’ was used in varying differing manners, and not always as we understand it now. At times it meant a United Front; at others a narrower circle; at times even a ‘sect’.

In 1914, Lenin emphasised the historical dimension when discussing how late the two founders “declared in favour of a special workers organisation”. Lenin’s explanation is entirely rational being the “enormous difference” between the German and the Russian movements:

“It was only in April 1849, after the revolutionary newspaper had been published for almost a year… that Marx and Engels declared themselves in favour of a special workers’ organisation! Until then, they were merely running an ‘organ of democracy’ unconnected by any organizational ties with an independent workers’ party. This fact, monstrous and incredible from our present-day standpoint, clearly shows us what an enormous difference there is between the German workers’ party of those days and the present Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party.”

V.I.Lenin, “Two Tactics of Social Democracy”, in Selected Works (Moscow, 1936), III, pp. 131-2.

Drawing artificial divisions on this question of the party between Marx and Engels on one hand, and Lenin on the party is not supported from the history and their late articles. But even with this call identified by Lenin, it took a little bit longer before the path became less cluttered, with the primary focus of completion of the bourgeois democratic revolution.

By 1872, Marx and Engels were cheering the Paris Commune on. This was indeed now the formed proletariat in action. They now became quite unequivocal about how a party was “indispensable” to “the triumph of the social revolution” – as they expressed it in the “Rules for the First International” writing that:

“Against the collective power of the propertied classes the working class cannot act, as a class, except by constituting itself into a political party, distinct from, and opposed to, all old parties formed by the propertied classes. This constitution of the working class into a political party is indispensable in order to insure the triumph of the social revolution and its ultimate end – the abolition of classes.”

Resolution on the establishment of working-class parties; Adopted by the Hague Congress as Article 7 of the General Statutes, September 1872; at:MIA

We now summarise the strategic shift of Marx and Engels, and the main forms of organisation that this shift marked. We then flesh this summary out with historical details.

4. A strategic shift before and after the Paris Commune

The organisational challenges of Marx and Engels revolution revolved around one strategic difference in aims, which was placed between the early and later part of their political lives.

Early on in their political organising, certainly up to around 1855-1860, the strategic thrust of revolution for Marx and Engels was to complete the bourgeois democratic revolution in the various countries where they lived in Europe. They recognised that the first wide-scale political struggles of the workers after its birth were largely around democratic struggles:

“With its birth begins its struggle with the bourgeoisie…

At this stage, the labourers still form an incoherent mass scattered over the whole country, and broken up by their mutual competition. If anywhere they unite to form more compact bodies, this is not yet the consequence of their own active union, but of the union of the bourgeoisie, which class, in order to attain its own political ends, is compelled to set the whole proletariat in motion, and is moreover yet, for a time, able to do so. At this stage, therefore, the proletarians do not fight their enemies, but the enemies of their enemies, the remnants of absolute monarchy, the landowners, the non-industrial bourgeois, the petty bourgeois. Thus, the whole historical movement is concentrated in the hands of the bourgeoisie; every victory so obtained is a victory for the bourgeoisie…“

‘Manifesto of the Communist Party’, by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels February 1848; At Marx/Engels Selected Works, Vol. One, Moscow, 1969, pp. 98-137;

Even after the stalled 1848 revolutions, Marx still considered that the proletariat’s representatives might remain too weak to take the democratic phase of revolution forward into the socialist phase. Not only was the proletariat too weak perhaps, but also perhaps it was objectively not in a position to overcome the forces ranged against it. Therefore, any victory of the proletariat will likely be simply scooped up by the bourgeois revolution. This was largely because those objective opposing forces were “determined” by “the modern division of labour”. Simply put, breaching the bourgeois revolution might be premature:

“The “injustice in property relations” which is determined by the modern division of labour, the modern form of exchange, competition, concentration, etc., by no means arises from the political rule of the bourgeois class, but vice versa, the political rule of the bourgeois class arises from these modern relations of production which bourgeois economists proclaim to be necessary and eternal laws. If therefore the proletariat overthrows the political rule of the bourgeoisie, its victory will only be temporary, only an element in the service of the bourgeois revolution itself, as in the year 1794, as long as in the course of history, in its “movement”, the material conditions have not yet been created which make necessary the abolition of the bourgeois mode of production and therefore also the definitive overthrow of the political rule of the bourgeoisie.“

Karl Marx; “Moralising Criticism and Critical Morality: A Contribution to German Cultural History; contra Karl Heinzen”; 1847; CW Vol 6 London 1976; p.312-40; also at Architexturez.net

Yet by 1850, increasingly Marx and Engels went beyond any potential ‘caged, hedged-in objectivity’. Now they argued that it was possible to break through. They argued, the movement could move directly from the democratic revolution into the socialist revolution – making the revolution ‘permanent’.

“While the democratic petty bourgeois want to bring the revolution to an end as quickly as possible, achieving at most the aims already mentioned, it is our interest and our task to make the revolution permanent until all the more or less propertied classes have been driven from their ruling positions, until the proletariat has conquered state power and until the association of the proletarians has progressed sufficiently far – not only in one country but in all the leading countries of the world – that competition between the proletarians of these countries ceases and at least the decisive forces of production are concentrated in the hands of the workers.“

Marx and Engels Address to the Communist League at MIA

But Marx and Engels only completely modified their strategic thrust towards bourgeois democracy finally and definitively after 1870 and the defeat of the Paris Commune.

Thereafter, their emphasis moved decisively away from elements of the democratic revolution, more clearly to the socialist revolution itself. But while the tactics of what could be called ‘United Frontism’ with other classes were less stressed after the fall of the Paris Commune – they never dropped such principled pragmatism. This was part of their falling out with Bakunin (see below).

In this light it is quite unsurprising that Marx and Engels only emphasised the need for a separate workers party relatively late.

What is more surprising – possibly – was how long, even after the Paris Commune this period of the democratic revolution was to extend. During this long phase the “Communist theoreticians” of the proletarian classes – felt they needed to utilise it. Both Marx and Engels defended the fight for universal suffrage (at least male suffrage) and democratic rights against Michael Bakunin in the International Working Men’s Association – and in the German Eisenach Party. This support extended up to the end of the long life of Engels. We do not further consider that aspect in this article, but return at a later time point to it.

We turn now to the specific forms taken by the organisations that Marx and Engels built or worked in over their political lives.

5. The Developmental forms of organisation undertaken by Marx and Engels

The exact developmental forms that the radical left took varied in the phases of the organisational lives of Marx and Engels. Several forms of organisation were undertaken, some of which overlapped in time. Nonetheless, the forms showed a clear progression.

i) Initially, secret societies were the revolutionary form of radical-left organising. They even survived in the years up to 1860, They had been inspired by models left by the most radical of the Jacobins – in the Babeuf Conspiracy. These were adopted by the adherents of Louis Blanqui.

ii) Mass labour parties followed, but at first only in the English Chartist movement. But already this was physically crushed by the 1850s. And then its clothes of suffrage, and democratic rights expressed in its ‘Six Points’ – were simply stolen by the bourgeoisie.

iii) Attempts to form similar working-class parties in other countries following the model of the Chartists, was directly linked to the International Working Men’s Association (IWMA). This was to follow the building of strong trades unions in these countries. However, the work of the IWMA was ultimately to founder upon the intrigues of the anarchists led by Mikhael Bakunin. It did not ultimately create major parties. The IWMA was effectively destroyed by the attempt to save it from the anarchist in a move across the Atlantic. It had not managed to create parties in the rest of Europe. On the dissolution of the IWMA Marx and Engels were left without any organisational base.

iv) The 1870 Paris Commune displayed that the time had come for firmer emphasis upon socialist demands.

v) In the meantime in Germany, once again the bourgeoisie stole the workers’ clothes, making democratic demands redundant. This made for a socialist party movement. But here followers of Marx and Engels in the German states, developed a large formal socialist party. The seeds of some of it were initially germinated by Ferdinand Lassalle. But a separate source was that of Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel, which was favoured by the founders of Marxism. By this time both Marx and Engels recognized the need for a party as distinct from but intimately linked to the working class.

Each of these corresponded to historical junctures. These junctures forced the views of Marx and Engels on ‘party’ to change over time – or perhaps better formulated as they incorporated historical moments in their organisation. The revolutionary forms of organisation were adjusted depending upon politico-historical circumstances. Even as they often used the same term ‘party’ at various junctures, it took on differing shades.

Throughout however, they always had a sense of a leading group of “theoreticians” who “no longer need to seek science in their minds; they have only to take note of what is happening before their eyes and to become its mouthpiece.” (Marx, “The Poverty of Philosophy” Ibid).

6. The first proletarian struggles – fighting “the enemies of their enemies” in the secret societies – and the 1848 revolution

When Marx first organised himself politically in any formal way in 1842, it was as editor of the journal the Rheinische Zeitung:

“In Prussia… Frederick William IV had declared his love of a loyal opposition,… the Rheinische Zeitung was founded at Cologne, with unprecedented daring, Marx used it to criticise the deliberations of the Rhine Province Assembly,… At the end of 1842, he took over the editorship himself and was such a thorn in the side of the censors that … at the beginning of 1843, the ministry… declared that the Rheinische Zeitung must cease publication… Marx immediately resigned as the shareholders wanted to attempt a settlement, but this also came to nothing and the newspaper ceased publication…”

Friedrich Engels; “Biographical overview (1869)“; at MIA

As noted above, both Marx and Engels knew that the proletariat gained from the democratic struggles – even if victory of those struggles meant the bourgeoisie also gained:

“At this stage, therefore, the proletarians do not fight their enemies, but the enemies of their enemies, the remnants of absolute monarchy, the landowners, the non-industrial bourgeois, the petty bourgeois. Thus, the whole historical movement is concentrated in the hands of the bourgeoisie; every victory so obtained is a victory for the bourgeoisie…“

‘Manifesto of the Communist Party’, by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels February 1848; Marx and Engels Selected Works, Vol. One, Moscow, 1969, pp. 98-137;

Naturally, after the Rheinische Zeitung was banned, Prussia was closed to Marx.

Therefore in 1843, Marx became co-editor of a new left-wing newspaper in Paris. This was the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals), financed by Arnold Ruge. Karl and his wife Jenny Marx, moved in October 1843 to Paris. Only one issue was published, which was quickly banned in the German states. However, Ruge then refused further funding for new issues.

Only now did Marx and Engels enter broader international organisational waters in Paris and Brussels. But these consisted of secret societies and conspiracist plots. Secret societies were the dominant organising form for radicals. They were influenced heavily by Louis Blanqui who in turn followed the Jacobin principles of François-Noël or Gracchus Babeuf. Conspiracy enabled a degree of evasion of the various police and spy agencies of absolutist states – or the increasingly reactionary counter-revolution following Robespierre’s fall. The secret societies reflected the peak inspiration of the Jacobins in expressing bourgeois-democratic goals:

“Blanqui… instructed his followers… (to) regard any acceptance of legality as treason to the revolutionary cause, and pursued their methods of secret organisation of a revolutionary elite side by side with other underground Radical groups which held to the Jacobin traditions of conspiracy. As in the 1830s and 1840s Paris was honeycombed by revolutionary clubs and societies…”

G.D.H.Cole “A History of Socialist Thought; Vol 2: Marxism and Anarchism 1850-1890; London 1954; p.135

“The first secret societies of the workers both in France and in Germany, those founded in the thirties and the forties of the nineteenth century, set before themselves as an aim the emancipation of the whole of labouring mankind… The unions of German handicraftsmen, the Exiles’ League (1834-1836), and the Federation (or League) of the Just (1836-1839), were formed in Paris, where they worked hand in hand with the French secret societies. At this period, Paris was full of political refugees who had assembled there after a series of revolutionary movements and outbreaks in Germany, Poland, Italy, parts of Russia, etc. It is true that most of these refugees, and the movements by the failure of which they had been brought to this pass, still exhibited bourgeois-democratic and not strictly proletarian characteristics. Consequently, although the secret societies of that day were international in outlook, the internationalism they professed was bourgeois-democratic; they preached the brotherhood of all “peoples,” the solidarity of all the oppressed against “tyrants,” etc.”

G. M. Stekloff; “ History of The First International”: Chapter 2; London. Martin Lawrence Limited 1928; 3rd Russian edition; at MIA

It was during this period that Marx first met Frederich Engels in September 1844 in Paris.

The two agreed that the new class of the proletariat would bring the new future of socialism into being. This was a new mass phenomenon.

But in turn, this meant that the secret society mentality was seen as a major problem for Marx and Engels. Mainly because secret societies could not engage the masses. In contrast to the open proletarian mass class, the secret society had an individualist secrecy.

Nonetheless, these societies remained the pervasive and dominant roles in the radical movements of the day. Consequently, Marx and Engels now began working with the Utopian ‘League of the Just’. This simply further deepened their doubts as to whether secret societies were actually organising the mass of workers.

In any case, any organisational plans were disrupted by having to move to Brussels in 1845. This became necessary after the Prussian monarch repeated petitioned the French government to expel Marx, which it duly did in 1845.

Engels expressly joined Marx in Brussels, as did many members of the ‘League of the Just’ or related organisations. These included Moses Hess, Karl Heinzen and Joseph Weydemeyer.

Their sojourn in Brussels was not long-lived, for it was at this time that the 1848 revolutions broke out. Marx was expelled from Brussels. But in the interim he went back to organise in Germany as described here. Later, he went to London, where his activity in the Communist League is described in the next section.

The 1848 revolutions hinged on establishing democratic rights and defeating the reactionary absolutist states and landed aristocratic systems. These were battles in which a class alliance combined the then still revolutionary European bourgeoisie with the working men of Europe.

As the bourgeois democratic revolutions swept across Europe, the states of Germany became volatile. Seeing possibilities of revolutionary changes, Marx and Engels returned to Prussia to work with the paper ‘Neue Rheinische Zeitung’ in 1848:

“On the outbreak of the Revolution of February 1848, Marx was banished from Belgium. He returned to Paris, whence, after the March Revolution, he went to Cologne, Germany, where Neue Rheinische Zeitung was published from June 1 1848 to May 19 1849, with Marx as editor-in-chief.“

V.I.Lenin; “Karl Marx”; 1914; at MIA

“In Rhenish Prussia, they (Marx and Engels – ed) took charge of the democratic Neue Rheinische Zeitung published in Cologne. The two friends were the heart and soul of all revolutionary-democratic aspirations in Rhenish Prussia. They fought to the last ditch in defence of freedom and of the interests of the people against the forces of reaction. The latter, as we know, gained the upper hand. The ‘Neue Rheinische Zeitung’ was suppressed. Marx, who during his exile had lost his Prussian citizenship, was deported; Engels took part in the armed popular uprising, fought for liberty in three battles, and after the defeat of the rebels fled, via Switzerland, to London.”

Vladimir Lenin Biographical Article on Fredrick Engels”; 1895; at: MIA

A summary of the League’s struggles in these battles through several countries was given in an “Address” by Marx and Engels:

“For a while, following the defeats sustained by the revolutionary party last summer, the League’s organization almost completely disintegrated…

As the immediate after-effects of our defeats gradually passed, it became clear that the revolutionary party needed a strong secret organization throughout Germany. The need for this organization, which led the Central Committee to decide to send an emissary to Germany and Switzerland, also led to an attempt by the Cologne commune to organize the League in Germany itself.

Around the beginning of the year several more or less well-known refugees from the various movements formed an organization in Switzerland which intended to overthrow the governments at the right moment and to keep men at the ready to take over the leadership of the movement and even the government itself.”

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels; “Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League; 1850; at MIA Address

Later in 1884, Engels described the overall bourgeois democratic principles driving the Rheinische Zeitung:

“In this way, when we founded a major newspaper in Germany, our banner was determined as a matter of course. It could only be that of democracy, but that of a democracy which everywhere emphasised in every point the specific proletarian character which it could not yet inscribe once for all on its banner. If we did not want to do that, if we did not want to take up the movement, adhere to its already existing, most advanced, actually proletarian side and to advance it further, then there was nothing left for us to do but to preach communism in a little provincial sheet and to found a tiny sect instead of a great party of action. But we had already been spoilt for the role of preachers in the wilderness; we had studied the utopians too well for that, nor was it for that we had drafted our programme.”

Frederick Engels; “Marx and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung (1848-49); Collected Works, Vol 26, p. 120; at dhspriory

Thus, for Marx and Engels, it was critical to be with the “actually proletarian side” even if it was not perfect, and they could “advance it further” – because the alternative was to “preach communism in a tiny sect” rather than be part of a “great party of action”.

After the defeat of the risings, Marx was placed on trial in Germany, acquitted, but was then exiled anew:

“The victorious counter-revolution first instigated court proceedings against Marx (he was acquitted on February 9, 1849), and then banished him from Germany (May 16, 1849). Firs,t Marx went to Paris, where he was again banished after the demonstration of June 13, 1849, and then went to London, where he lived until his death.“

V.I.Lenin; “Karl Marx”; 1914; at MIA

The failure of the 1848 revolutions was due to the domination of the movement by the by-now thoroughly frightened bourgeoisie. This class had gladly used the power of the workers to bring down absolutist and feudal rule. But the bourgeoisie then drew back because the revolution was coming too close to challenging bourgeois rule. They therefore suppressed the revolution before it was nearly finished.

Marx summarised the 1848-1850 revolutionary period as ‘poor incidents’, but also a portent of the proletariat’s own revolution:

“The so-called revolutions of 1848 were but poor incidents – small fractures and fissures in the dry crust of European society. However, they denounced the abyss. Beneath the apparently solid surface, they betrayed oceans of liquid matter, only needing expansion to rend into fragments continents of hard rock. Noisily and confusedly they proclaimed the emancipation of the Proletarian, i.e. the secret of the 19th century, and of the revolution of that century.“

Karl Marx. “Speech at anniversary of the People’s Paper” April 14, 1856; London; Marx and Engels Selected Works, Volume One, p. 500; and at Marx Speech MIA

As a result of continued exile and repression, both Marx and Engels ended up in London. Here they entered a new organisational phase.

7. The Communist League was still not quite beyond secret societies 1847 to 1852

Now based in London Marx and Engels joined the then still secret ‘Communist League’ in 1847. This was one of a series of national organising committees throughout the states of Europe. The Germans were like all the others, a small grouping.

In this period Marx and Engels more directly contended with the beliefs of Blanqui and Babeuf:

“Blanqi and Babeuf. . . insisted that the revolution must be made by a trained elite before the mass had been brought over to its side”;

G.D.H.Cole “A History of Socialist Thought; Vol 2: Marxism and Anarchism 1850-1890; London 1954; p. 54

In contrast, the ‘Communist League’ behaved far more openly. Again, Marx and Engels had insisted on this as a pre-condition to joining the Communist League. Howeve,r they thought of this organisation as at best a “pre-party” structure.

As Monty Johnstone remarks:

“that the Communist League, an international secret society comprising “only a small core” of militants, cannot be described as a political party even in the usual sense in which the term was most frequently used at the time and is applied in the Manifesto itself to the large national organizations in which the Communists were to work. As the Soviet Marx scholar E.P. Kandel argues… Marx and Engels saw the League only as “the germ, the nucleus” of their party, notwithstanding the fact that they called its programme the Manifesto of the Communist Party. The conditions of the time, he writes,”did not provide possibilities for the League of Communists to turn into a real party.”

Monty Johnston “Marx and Engels on the Concept of the Party”; Socialist Register 1967; p.121-158; citing E.P.Kandel “Marks I Engel’s “Orgnizatory Soyauza Kommunistov”; Moscow 1953; p.125

Despite Marx and Engels’s demands for openness, it must be admitted that the League faced a severe climate of repression. That hindered it from functioning completely openly.

While initially based on German exiles and refugees from the 1848 revolution, the League became much more influential than its size implies as it had an international scope:

“The Communist League was an international association of workers in a number of Western European countries, in which Germans predominated and which paid special attention to Germany. Although “for ordinary peace times at least” it was seen by Marx and Engels as “a pure propaganda society”, it was forced by the conditions of the time to operate as a secret society during most of the five years of its existence.”

Monty Johnstone; Socialist Register 1967; Ibid.

Marx and Engels were part of a “small core”, an “inconsiderable force” – of the “German Communist Party”:

“On the outbreak of the February Revolution, the German “Communist Party”, as we called it, consisted only of a small core, the Communist League, which was organised as a secret propaganda society. The League was secret only because at that time no freedom of association or assembly existed in Germany. Besides the workers’ associations abroad, from which it obtained recruits, it had about thirty communities, or sections, in the country itself and, in addition, individual members in many places. This inconsiderable fighting force, however, possessed a leader, Marx, to whom all willingly subordinated themselves, a leader of the first rank, and, thanks to him, a programme of principles and tactics that still has full validity today: the Communist Manifesto.”

Frederick Engels; ”Marx and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung” (1848-49) written 1884; Collected Works, Volume 26, p. 120; and at Engels NRZeitung dhspriory

But that “small core” of a “few hundred” became part of an “enormous mass” in the German 1848 “extreme democratic party” – and it ‘vanished’ in the struggle:

“The few hundred separate League members vanished in the enormous mass that had been suddenly hurled into the movement. Thus, the German proletariat at first appeared on the political stage as the extreme democratic party.”

Frederick Engels; ”Marx and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung (1848-49) written 1884; Collected Works, Volume 26, p. 120; and at Engels NRZeitung dhspriory

Again, before joining the secret society, Marx and Engels had insisted, that, as a minimum, an open and clear statement of purpose be made. Correspondingly, they were asked to write an open programme, which became known as “The Communist Manifesto”:

“In the spring of 1847 Marx and Engels joined a secret propaganda society called the Communist League. Marx and Engels took a prominent part in the League’s Second Congress (London, November 1847), at whose request they drew up the Communist Manifesto, which appeared in February 1848. With outstanding clarity, this work outlines a new world-conception based on materialism.”

V.I.Lenin; “Karl Marx”; 1914; at Lenin on Marx MIA

This counter-acted the remaining and necessary secrecy. That the Communist League had gained a visible prominence in the eyes of the masses was made clear by Marx and Engels in the March 1950 address:

“The League further proved itself in that its understanding of the movement, as expressed in the circulars issued by the Congresses and the Central Committee of 1847 and in the Manifesto of the Communist Party, has been shown to be the only correct one, and the expectations expressed in these documents have been completely fulfilled. This previously only propagated by the League in secret, is now on everyone’s lips and is preached openly in the market place…”

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels; “Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League”; London, March 1850; at: Address to Communist League MIA

During the 1848-9 revolutions, when the ranks of the League were “considerably weakened,” and the broader “workers’ party had lost its only firm foothold” – the League was “weakened and districts allowed their connections with the central Committee to weaken and become dormant”:

“At the same time, however, the formerly strong organization of the League has been considerably weakened. A large number of members who were directly involved in the movement thought that the time for secret societies was over and that public action alone was sufficient. The individual districts and communes allowed their connections with the Central Committee to weaken and gradually become dormant. So, while the democratic party, the party of the petty bourgeoisie, has become more and more organized in Germany, the workers’ party has lost its only firm foothold, remaining organized at best in individual localities for local purposes; within the general movement it has consequently come under the complete domination and leadership of the petty-bourgeois democrats.”

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels; “Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League”; London, March 1850; at: Address to Communist League MIA

This broader “workers party” which had lost its only “firm foothold in the League” – was the same “enormous mass” he had termed elsewhere (See above Frederick Engels; ”Marx and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung (1848-49). Clearly, there is a slightly differing and legitimate use of the term ‘party’ than the one subsequently used in present times.

In the “Manifesto,” the working class movement was the “only really revolutionary class”. The working class was left in the field facing the bourgeoisie on its own:

“… Of all the classes that stand face to face with the bourgeoisie today, the proletariat alone is a really revolutionary class. The other classes decay and finally disappear in the face of Modern Industry; the proletariat is its special and essential product.”

Marx and Engels, “Communist Manifesto”, 1848; Ibid

We saw that Lenin pointed out that only now did Marx and Engels separate out a purely workers organisation:

“It was only in April 1849, after the revolutionary newspaper had been published for almost a year… that Marx and Engels declared themselves in favour of a special workers’ organisation!”

V. I. Lenin, “Two Tactics of Social Democracy”, in Selected Works (Moscow, 1936), III, pp. 131-2.

Around the defeat of the German 1848 episodes, a split developed in the League, over ‘voluntarism’ – which was fought by Marx and Engels. We do not go into the details here. But this allowed the Prussian state to use its police and spies to concoct charges against Marx, including with falsified documents. After much delay because there was in fact no actionable data, the “Cologne Communist Conspiracy Case” of 1852 took place. That it was a police conspiracy of the government not the League – was exposed in open court. This was the effective end however of the League.

Engels in 1852, later summarised the 1848 period. In his over-view, he makes it clear that the societies were involved in the democratic struggles as a prelude ”to the great impending struggle… to prepare the party, whose nucleus” was being readied:

“there were some other societies which were formed with a wider and more elevated purpose, which knew, that the upsetting of an existing government was but a passing stage in the great impending struggle, and which intended to keep together and to prepare the party, whose nucleus they formed, for the last, decisive combat which must one day or another crush forever in Europe the domination, not of mere “tyrants,” “despots” and “usurpers,” but of a power far superior, and far more formidable than theirs; that of capital over labor.”

Frederick Engels; “The Late Trial at Cologne”; 1852; Collected Works, Vol 11, p. 388; 1852; at Architexturez Cologne Communist Trial

Once again, the sense of Engels’s summary was that the leaders – “the advanced Communist Party” would “study the causes (of the) revolutionary movements of 1848, and the causes that made them fail… it applied itself to the study of the conditions under which one class of society can and must be called on to represent the whole of the interests of a nation”:

“The organization of the advanced Communist party in Germany was of this kind. In accordance with the principles of its “Manifesto” (published in 1848) and… on Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany… this party never imagined itself capable of producing, at any time and at its pleasure, that revolution which was to carry its ideas into practice. It studied the causes that had produced the revolutionary movements of 1848, and the causes that made them fail. Recognizing the social antagonism of classes at the bottom of all political struggles, it applied itself to the study of the conditions under which one class of society can and must be called on to represent the whole of the interests of a nation, and thus politically to rule over it. History showed to the Communist party,…

how at the present moment two more classes claim their turn of domination, the petty trading class, and the industrial working class. The practical revolutionary experience of 1848-49 confirmed the reasonings of theory, which led to the conclusion that the democracy of the petty traders must first have its turn, before the Communist working class could hope to permanently establish itself in power and destroy that system of wages-slavery which keeps it under the yoke of the bourgeoisie. Thus the secret organization of the Communists could not have the direct purpose of upsetting the present governments of Germany. Being formed to upset not these, but the insurrectionary government, which is sooner or later to follow them, its members might, and certainly would, individually lend an active hand to a revolutionary movement against the present status quo in its time; but the preparation of such a movement, otherwise than by secret spreading of Communist opinions by the masses, could not be an object of the Association.”

Frederick Engels; “The Late Trial at Cologne”; 1852; Collected Works, Vol 11, p. 388; 1852; at Architexturez Cologne Communist Trial

The Cologne Conspiracy Case said Engels, marked the “curtain fall” of the first period of the “independent German workers movement” which led on to the International Working Men’s Association:

“With the sentence of the Cologne Communists in 1852, the curtain falls on the first period of the independent German workers’ movement… it lasted from 1836 to 1852 and, with the spread of German workers abroad, the movement developed in almost all civilized countries. Nor is that all. The present-day international workers’ movement is in substance a direct continuation of the German workers’ movement of that time, which was the first international workers’ movement of all time, and which brought forth many of those who took the leading role in the International Working Men’s Association. And the theoretical principles that the Communist League had inscribed on its banner in the Communist Manifesto of 1847 constitute today the strongest international bond of the entire proletarian movement of both Europe and America.”

Frederick Engels; “On The History of the Communist League”; 1885 in Marx and Engels Selected Works, Volume 3, Moscow 1970; at: Engels History Communist League

These formulations of Engels are once again, extremely close to those of Lenin’s later professional party revolutionaries.

So despite its size – the ‘Communist League’ was composed of only an estimated 2-300 persons – it was a bridge between the secret organisational phases of Marx and Engels to the mass phases including the International:

“The successor of the Exiles’ League and of the Federation of the Just was known as the Communist League (1847-1851). Under the instructions of this body, and in its name, Marx and Engels issued in 1845 the Manifesto of the Communist Party, which expounded the internationalist tendencies of the League, and proclaimed the historic mission of the proletariat, substituting for the old device of the Federation of the Just, “All men are brethren,” the new fighting call of proletarian internationalism, “Proletarians of all lands, unite.” Thus the Communist League was one of the harbingers of the International.“

G. M. Stekloff; “History of The First International”: Chapter 2; London. Martin Lawrence Limited, 1928; from the 3rd Russian edition; at Stekloff MIA

After the Cologne Case, the League was at an end. Marx suggested to the London District that it disband (CW Vol 39; Marx Letter to Engels 19 November 1852; p.247; at hekmatist.com )

Both Marx and Engels were relieved to return to their study after the bitter in-fighting of the splitters. Indeed Engels was quite scathing:

“At long last we again have the opportunity – the first time in ages – to show that we need neither popularity, nor the SUPPORT of any party in any country, and that our position is completely independent of such ludicrous trifles. From now on we are only answerable for ourselves…

Besides we have no real grounds for complaint if we are shunned by the petits grands hommes… haven’t we been acting for years as though Cherethites and Plethites (Tribes as cited in Solomon – Ed) were our party when, in fact, we had no party, and when the people whom we considered as belonging to our party, at least… didn’t even understand the rudiments of our stuff? How can people like us, who shun official appointments like the plague, fit into a ‘party?… one is able at least for a time to maintain one’s independence from this whirlpool, although one does, of course, end up by being dragged into it.”

Engels to Marx, 13 February 1851; CW Vol 38: p.289-90; and at hekmatist 1851

But this period would end, as he himself knew it would:

“This is the position we can and must adopt on the next occasion. Not only no official government appointments but also, and for as long as possible, no official party appointments, no seat on committees, etc., no responsibility for jackasses, merciless criticism of everyone.“

Engels February 13 1851; Ibid; hekmatist 1851

Notwithstanding their sense of relief from the ‘jackasses’ – Marx was within 4 months of dissolving the League – already contemplating a new recruitment:

“Already in March 1853, within four months of the dissolution of the League, Marx is writing to Engels: “We must definitely recruit our party afresh”, since the few adherents that he names, despite their qualities, do not add up to a party.”

Monty Johnston; Ibid; citing Dommanget M; “Les idees d”Auguste Blanqui”; Paris 1957; p. 355

Marx’s own choice of words in private letters was also informative. With the passage of eight more years, Marx’s 1860 letter to the poet Ferdinand Freiligarth reflected on the dissolution of the “Communist League”. Marx invokes the word “ephemeral” to emphasise that differing forms of organisations arise in particular circumstances and are “episodes”. To distinguish this from a wider movement, he uses the phrase “history of the party”. This latter takes on a wider significance:

“I would point out d’abord‘ that, after the ‘League’ had been disbanded at my behest in November 1852, I never belonged to any society again, whether secret or public, that the party, therefore, in this wholly ephemeral sense, ceased to exist for me 8 years ago…

Since 1852, then, I have known nothing of ‘party’ in the sense implied in your letter. Whereas you are a poet, I am a critic and for me the experiences of 1849-52 were quite enough. The ‘League’, like the société des saisons in Paris and a hundred other societies, was simply an episode in the history of a party that is everywhere springing up naturally out of the soil of modern society.”

K. Marx to Ferdinand Freiligrath, 29 February 1860; Collected Works Vol 41 London 2010; p.81-2; emphasis in original – also at Michael Harrison

So for Marx, organisations-parties like the Communist League were “ephemeral” episodes. In marked contrast to the party arising from the “soil of modern society” – in a much broader sense of a mass party. We believe this shows his understanding of a correspondence between the form of organisations demanded and the historical moment.

8. The first mass proletarian party of the workers – the Chartists 1838-1860

What about the Canardist implication that there is no distinction between the ‘Party” and the ‘class’?

In the time period between 1848-1860, there was actually only one party as such. One that is that was seen by Marx and Engels as existing for the workers. The Chartists in Britain had formed in1838, but it had taken the party until 1842 to shake off the bourgeois grip over it.

In his seminal work that heralded ‘Das Kapital’, Engels, in the 1845 “Condition of the Working Class in England” described the origins of Chartism. He saw in it the failure of the Trade Union movement to stop the most violent oppressions of the manufacturers on the workers. It was an expression of anger of the whole class:

“Since the working-men do not respect the law… they should wish to put a proletarian law in the place of the legal fabric of the bourgeoisie. This proposed law is the People’s Charter, which in form is purely political, and demands a democratic basis for the House of Commons. Chartism is the compact form of their opposition to the bourgeoisie. In the Unions and turnouts opposition always remained isolated: it was single working-men or sections who fought a single bourgeois… But in Chartism it is the whole working-class which arises against the bourgeoisie, and attacks, first of all, the political power, the legislative rampart with which the bourgeoisie has surrounded itself.”

Frederick Engels, ‘Condition of the Working Class in England” at Chapter 10 MIA

Chartism was rooted in bourgeois democratic demands including universal (male) suffrage. But it steadily became more “pronouncedly” a “working-men’s party”. This led to the 6-point Charter which was “harmless but sufficient to overthrow the whole English Constitution”:

“Chartism has proceeded from the Democratic party which arose between 1780 and 1790 with and in the proletariat, gained strength during the French Revolution, and came forth after the peace as the Radical party… it extorted the Reform Bill from the Oligarchs of the old Parliament by a union with the Liberal bourgeoisie, and has steadily consolidated itself, since then, as a more and more pronounced working-men’s party in opposition to the bourgeoisie. In 1838 a committee of the General Working-men’s Association of London, with William Lovett at its head, drew up the People’s Charter, whose six points are as follows: (1) Universal suffrage for every man who is of age, sane and unconvicted of crime; (2) Annual Parliaments; (3) Payment of members of Parliament, to enable poor men to stand for election; (4) Voting by ballot to prevent bribery and intimidation by the bourgeoisie; (5) Equal electoral districts to secure equal representation; and (6) Abolition of the even now merely nominal property qualification of £300 in land for candidates in order to make every voter eligible. These six points, which are all limited to the reconstitution of the House of Commons, harmless as they seem, are sufficient to overthrow the whole English Constitution, Queen and Lords included.”

Frederick Engels; “Condition of the Working Class in England”, 1845 – chapter ‘Labour Movements’; at Chapter 10 MIA

Because of this core of Six Points, by 1842 the blurring of the democratic-bourgeois groupings and the more determined proletarian parts of the Chartist movement was erased. Once again, the bourgeoisie wanted the power of the workers but feared its unleashing. Hence, they withdrew from the revolt of the workers that the bourgeoisie had itself initially incited:

“The crisis of 1842 came on… But this time the rich manufacturing bourgeoisie, which was suffering severely under this particular crisis, took part in it. The Anti-Corn Law League… assumed a decidedly revolutionary tone. Its journals and agitators used undisguisedly revolutionary language… these bourgeois leaders called upon the people to rebel… The fruit of the uprising was the decisive separation of the proletariat from the bourgeoisie. The Chartists had not hitherto concealed their determination to carry the Charter at all costs, even that of a revolution; the bourgeoisie, which now perceived, all at once, the danger with which any violent change threatened its position, refused to hear anything further of physical force,… “

Engels “Condition” Ibid at Chapter 10 MIA

But very quickly the Chartist party itself fractured into opposing ‘wings.’ Its ‘Left Wing’ was led by Julian Harney and Ernest Jones:

“In fact, at this time (1848 – ed) there was only one workers’ party organized on a national scale, the Chartists, and the British Communists, Julian Harney and Ernest Jones worked in it as leaders of its left wing.”

Monty Johnstone Ibid.

It was this party that Marx and Engels probably used as a model when writing the Communist Manifesto. As Johnstone writes:

“When Marx and Engels speak in the Manifesto of the “organization of the proletarians into a class, and consequently into a political party”, they clearly have in mind the English model. . . Chartists.”

Monty Johnstone p. 194-195

Marx recognised that this trade union struggle of the workers in the Chartists was ‘simultaneous’ with the political struggle:

“The organization of these strikes, combinations, and trades unions went on simultaneously with the political struggles of the workers, who now constitute a large political party, under the name of Chartists.”

Karl Marx, “The Poverty of Philosophy”; Chapter Two: The Metaphysics of Political Economy, Strikes and Combinations of Workers”; at Marx Poverty Philosophy MIA

But the Chartist “working-men’s movement” still had to develop its theory. It needed to “reproduce French communism in an English manner… in the next step”. This was necessary (“only, when this has been achieved”…) for the workers to lead England (“… will the working-class be the true intellectual leader of England“):

“it is evident that the working-men’s movement is divided into two sections, the Chartists and the Socialists. The Chartists are theoretically the more backward, the less developed, but they are genuine proletarians all over, the representatives of their class. The Socialists are more far-seeing, propose practical remedies against distress, but, proceeding originally from the bourgeoisie, are for this reason unable to amalgamate completely with the working-class. The union of Socialism with Chartism, the reproduction of French Communism in an English manner, will be the next step, and has already begun. Then only, when this has been achieved, will the working-class be the true intellectual leader of England.”

Frederick Engels; “The Condition of the Working Class in England”; Ibid at Chapter 10 MIA

So the first major major period of the political lives of Marx and Engels had focused on the struggle for bourgeois democratic rights which peaked in 1848.

But a new phase started around 1949, seeing a melding of two phenomena:

Namely the same completion of the revolution for democratic rights, together with the organising of the labour movement in Britain in the Chartist movement.

Historical situations had dictated how Marx and Engels changed their view of the ‘party’. These paralleled the development of the working class itself, corresponding to the form and temperature of the class struggle. As they themselves said:

“the proletariat not only increases in number; it becomes concentrated in greater masses, its strength grows, and it feels that strength more… Now and then the workers are victorious, but only for a time. The real fruit of their battles lies, not in the immediate result, but in the ever expanding union of the workers…

that was needed to centralise the numerous local struggles, all of the same character, into one national struggle between classes. But every class struggle is a political struggle…“

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels; ‘Manifesto of the Communist Party’, 1848; Marx and Engels Selected Works, Vol. One, Moscow, 1969, pp. 98-137

After the defeat of the 1848 revolutions, massive repressions followed. In addition, there was a forced emigration of myriads of the best revolutionary cadre. This had also affected the Chartists whose:

“leaders had been imprisoned and whose organisation had been dismembered, shattering the self-confidence of the English working class.”

Karl Marx ‘Capital’ Volume 1; 1867; Tr Fowkes London 1990; p.397

As Marx put it in his Inaugural Address to the “Working Men’s International Association”:

“After the failure of the Revolutions of 1848, all party organisations and party journals of the working classes were, on the Continent, crushed by the iron hand of force, the most advanced sons of labour fled in despair to the Transatlantic Republic, and the short-lived dreams of emancipation vanished before an epoch of industrial fever, moral marasme, and political reaction.”

Marx K, Inaugural Address of The Working Men’s International Association;

Established September 28, 1864 at a Public Meeting Held At St. Martin’s Hall, Long Acre, in Institute of Marxism-Leninism CC of the CPSU(B); “Preface”; in Documents of the IWMA Volume 1; The General Council Of the First International 1864 – 1866; the London Conference 1865”; London after Moscow edition nd; p.283; at Internet Archive

The next phase of revolutionary organisations saw Marx and Engels participating and leading attempts to rebuild a mass movement.

9. The “International Working Men’s Association” IWMA, or the First Communist International

The IWMA had two main characteristics and aims:

First, an intent to develop trade union solidarity; and,

Second, an intent to develop a broad United Front of progressive tendencies.

Marx and Engels in London were directly involved with leading Chartists. It was no coincidence that the movement had began in the homeland of the Chartists, in Britain:

“It was on British soil that the First International came into being, and this was no chance matter. In the first half of the nineteenth century, capitalist development was more advanced in Britain then anywhere else in the world. It was in England that there occurred the most vigorous development of the working-class movement of those days, a movement which in the form of Chartism, was the precursor of the future international social democracy. Till far on into the seventies…

England, where modern class contrasts had first made their appearance, remained the land where these contrasts were most marked. In England, therefore, all the most important forms of the proletarian class-struggle first broke out. England was the first country to offer history a political movement of the proletariat as a class.”

G. M. Stekloff; “History of The First International”: Chapter 2; London. Martin Lawrence Limited 1928; from 3rd Russian edition; at Stekloff MIA

The Chartist experience inspired from the start an ambitious international united front to bring together many working class, socialist and other trends:

“The revival of the democratic movements in the late fifties and in the sixties thrust Marx back into political work. In 1864 (September 28) the International Working Men’s Association – the First International – was founded in London. Marx was the heart and soul of this organization, and author of its first address and of a host of resolutions, declaration and manifestos. In uniting the labor movement of various forms of non-proletarian socialism (Mazzini, Proudhon, Bakunin, liberal trade-unionism in Britain, Lassallean deviations to the right, etc.), and in combating the theories of all these sects and schools, Marx here hammered out uniform tactics for the proletarian struggle of the working in the various countries. “

V.I.Lenin; “Karl Marx”; 1914; at Lenin Karl Marx’ MIA

It began explicitly as an international trade union alliance:

“The IWMA set up in London in 1864, began as a joint affair of the British and French trade Unions, with the participation of a number of exiles from other parts of Europe who were then living in London. It is important to understand that it began primarily as a Trade Union affair – as an expression of the solidarity of the organised workers of France and Great Britain – and not as a political movement. . .”

G.D.H.Cole “A History of Socialist Thought; Vol 2: Marxism and Anarchism 1850-1890; London 1954; p. 88

But it was calculated to also move workers into a political stand beyond economism. In fact, the ostensible reason for the London meeting was entirely political. Initially British workers had wanted to express solidarity with the Polish national rising of 1863, from working men over the continent, but especially France:

“The General Council’s policy on the Polish question was of special significance. Its members had not forgotten that one of the immediate factors responsible for the founding of the International was the protest, voiced by French and English workers at a joint meeting in St. James’s Hall on July 22, 1863, against the suppression of the Polish Insurrection of 1863. The demand that Poland’s independence be restored, a demand that was directed against tsarism, then one of reaction’s bulwarks in Europe, enabled workers in every country to expose the foreign policy of their own governments, since the Polish Insurrection had been suppressed with the direct or indirect connivance of all the European powers.”

“Preface”; in Institute of Marxism-Leninism CC of the CPSU(B); Documents of the IWMA Volume 1; The General Council Of the First International 1864 – 1866; the London Conference 1865”; London after Moscow edition nd; p.21; at Internet Archive

In his Inaugural Address to the IWMA Marx made the limits of economism and simple cooperation clear. His wording regarding leadership – paralleling the sense of Lenin’s later phrasing – could not have been made clearer for he used the words – “as the most intelligent leaders of the working class had already asserted in 1851 and 1852 against the cooperative movement in England” ;

“At the same time, the experience of the period from 1848 to 1864 has proved (In the German text was added: “was die intelligentesten Führer der Arbeiterclasse in den Jahren 1851 und 1852 gegenüber der Kooperativbewegung in England bereits geltend machen’’ -or “as the most intelligent leaders of the working class had already asserted in 1851 and 1852 against the cooperative movement in England”) beyond doubt that, however excellent in principle, and however useful in practice, cooperative labour, if kept within the narrow circle of the casual efforts of private workmen, will never be able to arrest the growth in geometrical progression of monopoly, to free the masses, nor even to perceptibly lighten the burden of their miseries. It is perhaps for this very reason that plausible noblemen, philanthropic middle-class spouters, and even keen political economists, have all at once turned nauseously complimentary to the very co-operative labour system they had vainly tried to nip in the bud…

To conquer political power has therefore become the great duty of the working classes. They seem to have comprehended this, for in England, Germany, Italy, and France there have taken place simultaneous revivals, and simultaneous efforts are being made at the political reorganisation of the working men’s party.”

Marx K, Inaugural Address Of The Working Men’s International Association; in Documents of the IWMA Volume 1; The General Council Of the First International 1864 – 1866; the London Conference 1865”; London after Moscow edition nd; p.283; at Internet Archive

Just as clearly, Engels made his distinctions between trade union work and political work clear also when he wrote privately to Marx about a proposal in Germany from one Becker:

“Dear Moor,

Old Becker must have gone completely off his head. How can he decree that the Trades Unions must be the real workers’ association and the basis of all organisation, that the other associations must only exist provisionally alongside, etc . And all in a country where real trades unions still do not yet even exist. And what a complicated ‘organisation’. On the one hand each trade centralises itself in a national leadership, on the other hand the various trades in each locality centralise themselves again in a local leadership. If one wanted to make the eternal squabbling permanent, this would be the arrangement to adopt. But it is au fond nothing but the old German journeyman’s desire to preserve his ‘inn’ in every town, and takes this to be the unity of the workers’ organisation. If many more such proposals come to light, the time at the Eisenach Congress will be nicely debated away.”

Engels to Marx July 30, 1869; Collected Works Vol p. 335; emphasis in original; at Wikirouge

But to become an effective mass organisation, the IWMA very deliberately balanced what was on the ground as really existing forces. These were very differing political tendencies and forces which needed to be joined into a united front. This included bourgeois radicals including such anti-socialists as the Italian Giuseppe Mazzini. Its goal was to build an international proletarian force – while not allowing bourgeois tendencies to drown it:

“In order to unite into one army the individual contingents of the European working-class movement, which stood at very diverse levels of development in matters of theory, Marx had to draw up a programme that would not shut the door upon the British trade-unionists, the French, Belgian, and Swiss Proudhonists, and the German Lassalleans. Only in this way could the mass character of the organisation be assured…

The primary task of the General Council at that stage was to safeguard the proletarian character of the International against the encroachments of bourgeois politicians who sought to use the upsurge in the working-class movement in their own ends. To cope with this task the Council had itself first to become a militant, efficient, authoritative, and proletarian body,… Besides leaders of the British trade unions and of the German, French, Italian, and Polish proletarian and petty-bourgeois émigrés in London, there were representatives of the English bourgeois radical and democratic movement, bourgeois co-operators, and men active in bourgeois philanthropic cultural and educational societies for workers, etc… By the spring of 1865, when a considerable part of the bourgeois element had left the Council, it became an essentially international working-class body that most fully represented diverse contingents of the European proletariat.”

Institute of Marxism-Leninism CC of the CPSU(B); “Preface”; in Documents of the IWMA Volume 1; The General Council Of the First International 1864 – 1866; the London Conference 1865”; London after Moscow edition nd; p.12;14;15-16; Ibid; at Internet Archive

With such a determined proletarian stand, the more openly bourgeois elements, including those of the Italian republican Mazzini – left the IWMA. But thereafter various other leftist tendencies attempted to take over the IWMA. From 1868 onwards, the battles of Marx and Engels to organise the IWMA were largely against anarchism as espoused by Mikhail Bakunin. The latter argued against any collaboration with the bourgeoisie; and against any form of state.

In contrast Marx and Engels continued to recognise the need and virtue at times for an alliance with elements of the bourgeoisie for:

“policies which made it easier for the workers’ movements to operate and to extend their presure for social reforms within the existing system.”

G.D.H.Cole “A History of Socialist Thought; Vol 2: Marxism and Anarchism 1850-1890; London 1954; p. 118

Marx and Engels also saw that rather than fighting for any dissolution of states or ‘no states’ – the fight should be for a workers’ state:

“Bakunin (and allies) were out-and-out opponents of the State in all forms… Marx denounced… the ‘police state’ of the feudalists and capitalists, while he was seeking to overthrow and to supersede with a new state – a Volkstatt – based directly on the power of the working class.”

Cole G.D.H.; Ibid p. 117

However, the Bakunin forces in especial led from Switzerland and Spain, worked in secret to subvert the IWMA. They wanted the prestige of the IWMA but not its discipline over themselves. To preserve the best of the forces internationally, the IWMA was moved to New York in 1872 following the Hague Congress. However it there died for lack of the drive of Marx in particular. F.A.Sorge as the new General-Secretary, was simply overwhelmed by the responsibility and required tasks (G.D.G.Cole Ibid p. 202).

But there were also other forces that pushed for its demise, in particular after the fall of the Paris Commune:

“Following the downfall of the Paris Commune (1871)… and the Bakunin cleavage in the International, the organization could no longer exist in Europe. After the Hague Congress of the International (1872), the General Council of the International had played its historical part, and now made way for a period of a far greater development of the labor movement in all countries in the world, a period in which the movement grew in scope, and mass socialist working-class parties in individual national states were formed.“

V.I.Lenin; “Karl Marx”; 1914; Lenin on Marx at MIA

We cannot go further at this point into the reasons for the disintegration of the IWMA at this time. (But see also Alliance ML No 19; and Alliance ML No.36 on Bakunin)

After the frenzy of the IWMA and its dissolution, Marx and Engels re-entered their theoretical work. Before we dive into the next major period of organisation however, it is worth considering how Marx summarised his understanding of the IWMA in the context of party development.

In his letter to Frederich Bolte in New York of 1871, discusses the dissolution of the First International (the IWMA). Marx here now makes a point about ‘sects’, which he contrasts with the ‘real organisation of the working class’ – the two “standing in inverse ratio to each other”:

“The International was founded in order to replace the Socialist or semi-Socialist sects by a real organisation of the working class for struggle. The original Statutes and the Inaugural Address show this at the first glance. On the other hand the Internationalists could not have maintained themselves if the course of history had not already smashed up the sectarian system. The development of the system of Socialist sects and that of the real workers’ movement always stand in inverse ratio to each other. So long as the sects are (historically) justified, the working class is not yet ripe for an independent historic movement. As soon as it has attained this maturity all sects are essentially reactionary. Nevertheless what history has shown everywhere was repeated within the International. The antiquated makes an attempt to re-establish and maintain itself within the newly achieved form.”

Marx to Friedrich Bolte In New York; November 23, 1871; at MIA Marx to Bolte 1871

While Marx inversely weighs the two – both are explicable. Even “sects” are “historically justified” – when the working class has not yet become an “independent historic movement”. They reflect an immaturity of the movement. This is, in essence – exactly the same sense as was conveyed by prior quotation from Engels.

From both their actions and their words, Marx and Engels did not eschew small-p political partying when warranted. But they placed such activity as a preparation before the real movement of the class, the broader Party.

10. Era of the national mass party (Germany 1870s-90s; Britain and America 1880s- 90s)

A large working class Party did develop in Germany by 1881. And it was in the end, heavily influenced by Marx and Engels.

“Germany has had for more than ten years a Working Men’s party (the Social-Democrats), which owns ten seats in Parliament, and whose growth has frightened Bismarck into those infamous measures of repression of which we give an account in another column. Yet in spite of Bismarck, the Working Men’s party progresses steadily.”

Engels; “A Working Men’s Party”; 1881; Engels 1881 MIA

But its’ origin nonetheless was rather circuitous, and Marx and Engels were not initially involved in the first German party. Rather it was Ferdinand Lassalle who first started the germ of a party. It was called the General German Workers’ Association.

This is not the place to examine the core differences between Lassalle and Marx-Engels. Here, we focus only on party formation and attitudes to it.

Unfortunately Lassalle became the pawn of the government led by Otto von Bismarck who was looking for “a socialistic agitator.. as a tool”. As Wilhelm Liebknecht reported to the General Council of the IWMA: