Revisionism in Germany Part One: to 1922

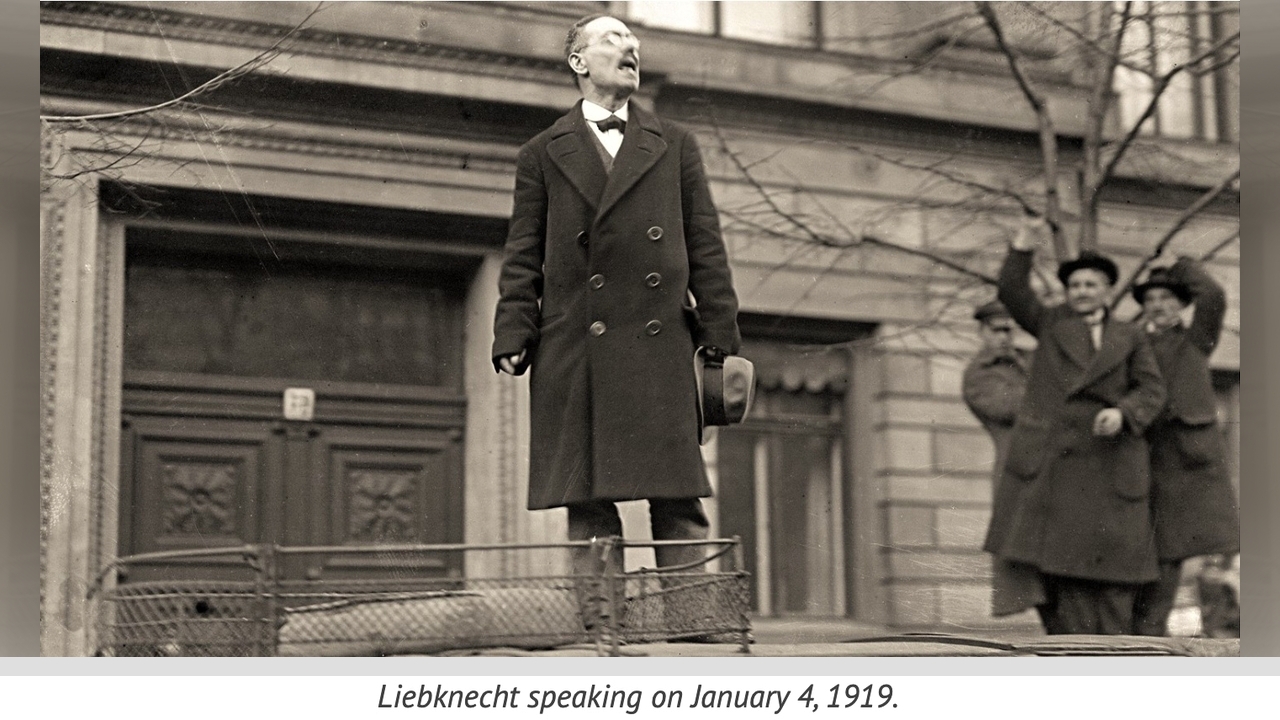

Image from International Publishers New York 1927 at: Karl Liebknecht

REVISIONISM IN GERMANY PART ONE: to 1922

W.B.Bland for THE COMMUNIST LEAGUE January 1977, London UK.

Reprinted Alliance: January 2001 at Alliance ML 2001

INTRODUCTION (Bland W.B. 1977)

Continuing the series of reports on the development of revisionism in the international communist movements, the report which follows deals with Germany in the period up to the end of 1922. Among the more important points covered in this report are:

1) The influence on the Communist Party of Germany (CPG) in its early years of the thoughts of Rosa Luxemburg, whose ideas on many political questions were closely akin to those of Leon Trotsky (See Appendix: p. 82);

2) The opposition of the CPG, under the influence of the anti-Soviet views of Luxemburg, to the formation of the Communist International (p. 18);

3) The strong “leftist” trends in the leadership of the CPG in its early years – manifested in its opposition to work in the mass trade unions (p. 13), its boycott of the elections to the Constituent Assembly, in 1919 (p. 17); its’ initial refusal to oppose the counter-revolutionary Kapp Putsch in 1920 (p. 29), its’ adoption of “the theory of the general revolutionary offensive” and the manifestation of this theory in the premature “March Action!” of 1921 (p. 43);

4) the adoption by the Communist International, under the influence of the anti-Soviet views of Leon Trotsky, in 1921 of the right revisionist concepts that a “workers’ government” – a coalition government of Communists and Social-democratic Parties – representing the “interests of the working class” could be formed by parliamentary means and could proceed to take control of production and transform the capitalist state into a workers’ state” (p. 61).

PART ONE: 1871 to 1917

The unified German state officially came into-existence in January 1871, by means of the armed force of the aristocratic landowners of Prussia (the Junkers), under the leadership of Count Otto von Bismarck. The bourgeoisie supported, but did not lead, this movement,

Formally, the Second German Reich (i.e., Realm) — the first Reich was the- mediaeval Holy Roman Empire — was a federal state embracing 4 kingdoms (Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony and Wurttemberg), 6 grand duchies, 5 duchies, 7 principalities, 3 “free cities” and the “Reichsland” of Alsace-Lorraine.

Because of the manner of its formation, however, the new state was an autocracy retaining many of the characteristics of a feudal state dominated by the Junkers of Prussia (where the franchise was limited to the well-to-do), and this ruling class was closely linked with the officer ‘corps of the German army (which was essentially the Prussian army) and with the imperial house (the King of Prussia was constitutionally the Emperor of Germany). The Emperor was supreme commander of the army and navy. The Parliament (Reichstag) was elected by universal male suffrage, but its role was essentially “advisory”.

There was at this time no German cabinet. The one Minister was the Imperial Chancellor, who was appointed by the Emperor and was also Prime Minister of Prussia. The Chancellor – Bismarck until March 1890 – appointed the heads of the departments of state and presided over the Federal Council.

The first party to be formed in Germany claiming to represent the interests of the working class was the General German Workers’ Association (Allgemeine Deutsche Arbeiterverein) (ADAV), founded in May 1863 under the leadership of Ferdinand Lassalle.

As Marx and Engels correctly concluded, Lassalle had signed a secret agreement with Bismarck, by which he undertook to strive to direct the working class into alliance with the Prussian aristocratic landowners, into:

“Alliance with absolutist and feudal opponents against ….the bourgeoisie.”

(K. Marx: “Critique of the Gotha Programme” in: “Selected Works” Volume 2; London; 1943; p. 570).

so that :

“Lassalle’s Organisation is nothing but a sectarian organisation and as such hostile to the Organisation of the genuine workers’ movement”.

(K. Marx: Letter to A. Bolte, November 23rd., 1871, in: ibid.; p. 616-7).

It was in these circumstances that in August 1869 a rival party claiming to represent the interests of the working class was established — the Social-Democratic Workers’ Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei) (SDAP), under the leadership of Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel, which was influenced by Marx and Engels.

In May 1875 the two parties merged at a Unification Congress held In Gotha into the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany (Sozialistische Arbeiterpartel-Deutschlands (SAPD). The desire of the leaders of the SDAP for unification with the ADAV was such that they agreed to the opportunist programme adopted at the congress (known as “the Gotha Programme”); this was a mixture of Lassallean and distorted Marxist ideas with the former predominating, and was strongly criticised by Marx, who described it as:

“a thoroughly objectionable programme tending to demoralise the party… The programme is no good, even apart from its sanctification of Lassallean articles of faith”.

(K. Marx, Letter to Wilhelm Bracke, May 5th; 1875, in: ibid.; p.552)

While Engels remarked:

“This programme… is of such a character that if it is accepted Marx and I can never give our adherence to the new party established on this basis, and shall have very seriously to consider what our attitude towards it – in public as well – should be.”

(F. Engels: Letter to A. Bebel, March 18-28th , 1875, In K.Marx Ibid; p. 593)

Two attempts on the life of the Emperor in May and June 1878 provided the official pretext for the passage in October of that year of an Anti-Socialist Law which banned all socialist parties, their publications and their meetings. This repressive legislation was renewed periodically until, with the increasing influence of the capitalist class, on the accession of Wilhelm II as Emperor in 1888 the authorities decided to replace the policy of attempted repression of the worker’s party with one of striving to transform it into a political instrument of the ruling class among the workers. Bismarck was forced to resign as Chancellor in 1890, and the Anti-Socialist legislation was allowed to lapse.

However, the long years of repression had exposed many illusions about the character of the state and pressed the rank-and-file in the direction of revolutionary thinking. As a result, the programme adopted by the Second Congress of the party, held at Erfurt in October 1891, was ostensibly Marxist in its formulations. At this congress the name of the party was changed to the Social-Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutchlands) (SPD).

With the development of German monopoly capitalism, in the last decade of the 19th century SPG leader Eduard Bernstein began a Movement to revise Marxism by removing its revolutionary content. Although revisionism was rejected in theory at the Congress of the party held in Dresden in September, 1903, the party became increasingly revisionist in practice. This was seen most obviously in the attitude of the SPG leaders who held important posts in the trade union movement; under their influence., the trade unions became less and less organs of working class struggle and more and more instruments of the monopoly capitalists to foster peaceful “industrial relations”.

It was under these circumstances that the membership of the SPG grow from 348,000 in 1906 to 1.1 million in 1914. By this time it was the largest single party in the Reichstag (with 110 deputies) and operated 110 daily newspapers, headed by “Vorwarts” (Forward) published in Berlin.

As the clouds of the First Imperialist War began to gather the Seventh Congress of the Second International held in Stuttgart in August 1907 adopted a resolution sponsored by Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg (the latter then representing the Polish Social-democrats) which called upon socialists:

“To exert every effort to prevent the outbreak of war by the means they consider most effective. . . In case war should break out anyway, it is their duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and with all their powers to utilise the economic and political crisis created by the war to rouse the masses and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule”.

(‘Resolution of 7th International Socialist Congress, cited in: V, I. Lenin: “Collected Works”, Volume 18; London; 1930; p. 468).

The Stuttgart anti-war resolution was reaffirmed at an Extraordinary Congress of the Second International held in Basle in November 1912, the manifesto adding:

“It is with satisfaction that the Congress records the complete unanimity of the, Socialist parties and of the trade unions of all countries in the war against war”.

(Manifesto of the Extraordinary International Socialist Congress, cited in: Lenin: ibid.; p. 469).

However, when on August 4th., 1914 German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg announced in the Reichstag that German troops had invaded Belgium, the SPG deputies voted unanimously in favour of war credits for “the war of National defence”.

On the same evening Rosa Luxemburg organised a few left-wing friends into the nucleus of what shortly became the International Group (Gruppe Internationale) to carry forward—the line of opposition to the war which had been agreed upon internationally, in Stuttgart and Basle.

The group was then joined by SPG deputy Karl Liebknecht who speedily regretted his vote for war credits. When the second War Credits Bill came before the Reichstag in December 1924, Liebneckt voted against it. In January 1915 the International Group began to issue a series of “Newsletters” exposing the character of the war and the treachery of the leadership of the SPG in supporting it. In-April 1915 they published the first and only issue of the journal “The International” (Die Internationale), under the editorship of Franz Mehring. It was immediately suppressed and Mehring imprisoned.

In an effort to check the increasing support which the International Group was now winning among the more politically conscious workers, in June 1915, a group of leading members of the SPG, headed by Karl Kautsky, Hugo Haase and Eduard Bernstein, took up a centrist position in relation to the war and issued a manifesto entitled: “The Demand of the Hour” – which suggested that the war might have changed its character from a “war of national defence”, to one of conquest, so that social-democrats might have to review their support of it.

In September 1915 an international conference of socialist parties and groups opposed to the war was held in Zimmerwald (Switzerland) on the initiative of the Italian and Swiss social-democratic parties. The Bolshevik delegation included Lenin, then living in Switzerland, and the German contingent included Georg Ledebour (associated with the Centrist group being developed under the leadership of Karl Kautsky), two adherents of the International Group and two members of a small group called the International Socialists of Germany (Internationale Sozialisten Deutschlands), led by Karl Radek. The conference failed to reach agreement on the policy that should be pursued in relation to the war, Lenin’s call for the war to be transformed into a civil war against “one’s own” imperialists being rejected by the majority of the delegates. With centrist groups in the majority the conference approved a compromise manifesto which called on socialists:

“to take up this struggle for. . . a peace without annexations or war indemnities”,

and

“For the sacred aims of Socialism, for the emancipation of the oppressed nations as well as of the enslaved classes, by means of the irreconcilable proletarian class struggle. ”

(Manifesto of the International Socialist Conference at Zimmerwald, cited in: V.I. Lenin: ibid; p.475).

The Zimmerwald conference set up an International Socialist Committee, with headquarters in Berne, Switzerland.

In January 1916, the International Group changed its name to the Spartacus Group (Spartakusgruppe), after the leader of a Roman slave revolt.

When the sixth War Credits Bill came before the Reichstag in March 1916, 18 deputies belonging to the centre and left of the SPG voted against, and a further 14 abstained. The rightist leadership of the SPG then expelled from the parliamentary party the 18 deputies who had voted contrary to the official policy of the party. These then formed themselves into a new parliamentary grouping, the Social-Democratic Labour Group (Sozialdemokratische Arbeitsgemeinschaft) . The Spartacus Group formed a left- wing group within this Labour Group.

In April 1916 a second international conference of socialist parties and groups opposed to the war was held at Kienthal (Switzerland). The German contingent consisted of four centrists and two Spartacists, together with one member of a small group called the Bremen Left (Bremen Links). Again the centrists were in a majority and the resolutions adopted were of a compromise character.

Nevertheless, the Kienthal resolutions were somewhat more definite than those of Zimmerwald, and the conference sharply criticised the leadership of the Second International — without, however calling for a break with the right.

Following their successful military operations on the eastern front, in August 1916 Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg had been appointed Chief of Staff and General Erich von Ludendorff Quartermaster-General. Although officially subordinate to Hindenburg, Ludendorff became the dominant figure not only in the military but also in the civilian field, and for the last two years of the war was essentially military dictator of Germany.

In January 1917 the Executive of the SPG, dominated by the right-wing social-chauvinists, resolved that opposition to the war was incompatible with membership of the party. This was followed in April by a conference of centrist and left opposition members of the SPG at Gotha, at which — against the opposition of Kautsky and other centrist leaders – a majority voted to form themselves into a new party, the Independent Social-democratic Party of Germany (ISPG), (Unabhangige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands) (USPD). The founding conference of the

ISPG approved the manifestos adopted at Zimmerwald and ‘Kienthal, but the leadership maintained its call for eventual reunification with the SPG:

“This party is.. afraid of drawing the necessary conclusions, preaches ‘unity’ with the social-chauvinists on an international scale, continues to deceive the masses of the workers with the hope of restoring this unity in Germany, and hinders the only correct tactics of revolutionary struggle against “one’s own government”.

(Lenin V.I. “The Stockholm Conference”., in: V I. Lenin & J.V.Stalin: “1917: Selected Writings and Speeches”, Moscow; 1938; p. 325) .

The formation of the ISPG (in which the Spartacus Group formed a left-wing group). was followed by a considerable fall in the influence of the SPG; membership of the latter fell from 243 thousand in March 1917 to 150 thousand in September, by which time the ISPG claimed a membership of 120 thousand.

By 1917, therefore, three organised political trends were to be seen in the German working class movement as characterised by Lenin:

“In the course of the two and half years of war the international Socialist and labour movement in every country has evolved three tendencies . . .

The three tendencies are:

1) The social-chauvinists, i.e., Socialists in word and chauvinists in action, people who are in favour of ‘national defence’ in an imperialist war (and particularly in the present imperialist war).

These people are our class enemies. They have gone over to the bourgeoisie.

They-include the majority of the official leaders of the official Social-Democratic parties in all countries — . . . the Scheidemanns in Germany.

2) The second tendency is what is known as the ’Centre’ consisting of people who vacillate between the social-chauvinists and the true internationalists.

All those who belong to the ‘Centre’ swear that they are Marxists and internationalists, . . . that they are for a peace without annexations, etc. and for peace with the social-chauvinists. The ‘Centre’ is for ‘unity’, the ‘Centre’ is opposed to a split . . .

The fact of the matter is that the ‘Centre’ is not convinced of the necessity for a revolution against one’s own government; it does not preach revolution.. . .

Historically and economically speaking, they (i.e. the, centrists — Ed.) do not represent a separate stratum but are a transition from a past phase of the labour movement to a new phase a phase that became objectively essential with the outbreak of the first imperialist World War, which inaugurated the era of social revolution.

The chief leader and representative of the ‘Centre’ is Karl Kautsky.

3) The third tendency, the true internationalists, is most closely represented by the ‘Zimmerwald Left’. . . .

It is characterised mainly by its complete break with both social-chauvinism and ‘Centrism’, and by its relentless war against its own imperialist government and against its own imperialist bourgeoisie.

… The, most outstanding representative of this tendency in Germany is the Spartacus Group or the Group of the International, to which Karl Liebknecht belongs. …Another group of internationalists in deed in Germany is gathered around the Bremen paper ‘Arbeiterpolitik‘”.

(V. I. Lenin: “The Tasks of the Proletariat in Our Revolution”, In “Selected Works”; Volume 6; London; 1946; p.63-66, 67).

The Russian bourgeois-democratic revolution of March 1917, followed by the formation of the Independent Social-Democratic Party in April, forced the German imperialists to make some token concessions to the sentiment reflected in the growth of the influence of the ISPG. These moves were led by Mattias Erzberger, leader of the liberal wing of the Centre Party, in the hope that government pledges to wage a ‘defensive’ war ‘without annexations or indemnities’ and to introduce democratic reform of the Prussian constitution would assist the right-wing SPG leaders in maintaining their support among the workers. As a result of these manoeuvres, a royal proclamation of July 12th, 1917; promised direct, secret and equal franchise in Prussia and on July 19th, the Reichstag adopted (by 214 votes to 116) its famous demagogic “peace resolution”, which declared:

“The Reichstag strives, for a peace of understanding and lasting reconciliation of nations. Such a peace is not in keeping with forcible annexations of territory or forcible measures of political, economic or financial character”.

(Cited in K.A.Pinson: “Modern Germany: Its History And Civilisation”; New York, 1966; p. 334).

The German High Command was fiercely opposed to these moves. Ludendorff demanded and secured-the resignation of Bethmann-Hollweg as Chancellor. The latter was ‘replaced in July 1917 by a civil servant, Dr. Georg Michaelis, who gave way in November to Count Georg von Hertling, leader of the right-wing of the Centre Party – both of which were completely subservient to the High Command,

1918

The January 1918 Strike

During the winter of 1917-18, anti-war feeling among the more politically conscious workers was greatly stimulated by the socialist revolution of November 1917 in Russia, and by the appeal of the new Soviet government for a peace without annexations or indemnities.

In January 1918 a group of militant shop stewards, associated with the Independent Social-Democratic Party and headed by Richard Muller issued a manifesto calling for

A political strike of all German workers for peace, more food, the abolition of martial law and the establishment of “parliamentary democracy”. The strike began on January 28th, and more than a million workers responded. After a week, however, it was called off by the leaders (against the opposition of the Spartacists) when the government merely agreed to met a delegation from the strike committee. Muller was then called up for military service, and the leadership of the “Revolutionary Shop Stewards” (as they called themselves) passed to another leading member of the ISPG, Emil Barth.

The formation of Prince Max’s Government

During the spring and summer of 1918, the suffering, hunger and casualties resulting from the war caused anti-war feeling to spread to wide sections of the German armed forces, the working class and the petty-bourgeoisie.

By the end of September a majority of the High Command were convinced that a German victory was not possible. They demanded the formation of a “broader” government that would proceed immediately to enter into negotiations with the Allies for an armistice. On October 3rd, Prince Max of Baden, a cousin of the Emperor, was appointed Chancellor and at once initiated negotiations for an armistice.

The Kiel Revolt

On October 27th, 1918, while the armistice negotiations were in progress, the Admiralty ordered the fleet to put to sea to engage the British navy. The sailors at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven refused. The arrest of some of these sailors in Kiel was followed on November 3rd, by a mass demonstration, which was fired on by troops, who later however, went over to the side, of the mutinying sailors. The latter released their arrested comrades, hoisted the red flag and proceeded to elect “Sailors Councils“, modelled on the Russian Soviets.

The Bourgeois-Democratic Revolution

The movement of revolt spread from Kiel throughout Germany. In all the major towns and cities, mass strikes and huge demonstrations demanded the abdication of the Emperor and the democratisation of the country. Everywhere informally elected Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils; (Arbeiter- Soldaten-Rate) took over the functions of local government. Troops and police either faded away or joined the revolution revolutionary crowd. In Hamburg, Spartacists took over the SPG newspaper and renamed it “The Red Flag” (Die Rote Fahne).

The capitalists now saw the necessity of using this spontaneous movement of revolution to complete the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Germany, hoping that by the sacrifice of the Emperor and the adoption of minor constitutional reforms they could contain the revolutionary process within the framework of “parliamentary democracy”. They also hoped that these steps might mitigate the peace terms, to be expected from the victorious Allied powers.

On November 7th, Prince Max had a secret meeting with the leader of the Social-Democratic Party, Friedrich Ebert, and was assured by the latter that the SPG would do all in its power to help stave off “the threat of Bolshevism”. (Prince Max of Baden: “Memoirs”, Volume 2;- London; 1928; P. 312).

As the chancellor was to express it later:

“I said to myself that the Revolution was on the point of winning, that it could not be beaten down, but might perhaps be stifled. Now is the time to come out with the abdication, with Ebert’s Chancellorship, with the appeal to the people to determined its own constitution, in a constituent National Assembly. If Ebert is presented to me as tribune of the people by the mob we shall have the Republic – if Liebknecht is, we shall have Bolshevism as well. But should Ebert be appointed Imperial Chancellor by the Kaiser at the moment of abdication, perhaps we should then succeed in diverting the revolutionary energy into the lawful channels of an election campaign”.

(Prince Max of Baden: ibid.; p.351).

Wilhelm was, however, reluctant to give up the throne, and shortly before noon on November 9th., without waiting for the Emperor’s agreement, the Chancellor issued the following statement:

“The Kaiser and King has resolved to renounce the throne. The Chancellor remains in office until the questions connected with the abdication of the Kaiser, the renunciation by the Crown Prince of the German Empire and of Prussia, and the setting up of the Regency have been regulated. He intends to propose to the Regent the appointment of Herr Ebert to the Chancellorship and the bringing in of a bill to enact that election writs be issued immediately for a German Constituent National Assembly“.

(Cited in Prince Max of Baden: ibid.; p. 353) .

The Emperor immediately departed into exile in Holland.

The time factor made it impracticable to go through the motions of appointing a Regent, who would in turn appoint Ebert as Chancellor, and the transfer of the Chancellorship from Prince Max to Ebert was the only un-constitutional act of the 1918 revolution.

Ebert immediately issued a vaguely worded communique, signing it as “Reich Chancellor”, which declared:

“The new government will be a people’s government, Its goal will be to bring peace to the German people as soon as Possible, and to establish firmly the freedom which it has achieved. Fellow citizens! I implore you most urgently to leave the streets and maintain calm and order!”

(Cited in: K. S. Pinson: “Modern Germany: Its History and Civilisation”; New York; 1966; p. 362).

Meanwhile Karl Liebknecht, on behalf of the Spartacists, was at four o’clock in the afternoon, raising the red flag over the royal palace and proclaiming to an enthusiastic crowd that Germany would be a socialist republic.

On November 10th, a secret meeting took place between Ebert and General Wilhelm Groener, representing the High Command.. at which Ebert obtained a pledge of the army’s full support “to prevent the spread of terroristic Bolshevism”. (D. Groener-Geyer: “General Groener: Soldat und Staatsmann”; Frankfurt; 195,5; p. 190-201) .

The Meeting of the Berlin Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils

That evening (November 10th), some 3,000 members of Workers’ and Soldiers, Councils in Berlin met at a large hall in the city, the Zirkus Busch. They carried a resolution declaring Germany to be a “socialist republic” with power in the hands of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils, calling for speedy socialisation of the means of production, expressing pride in following the example of the Russian Revolution, and calling for resumption of diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia.

They elected an “Executive Council” (Vollzugsrat) modelled superficially on that of Soviet Russia and composed of 24 workers and 24 soldiers, half from the SPG and half from the ISPG. They also elected a new cabinet, called, in imitation of that in Soviet Russia, the “Council of People’s Commissars” (Rat der Volksbeauftragten), composed of 3 members of the SPG and 3 members of the ISPG, headed by Ebert of the SPG.

The Foundation of the Spartacus League

At a conference in the Exzelsior in Berlin on November 11th, 1918, the Spartacus Group transformed itself into the Spartacus League (Spartakusbund).

The conference elected a Central Bureau (Zentrale) as follows – Willi Budich, Hermann Duncker, Kate Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Leo Jogiches, Paul Lange, Paul Levi, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Franz Mehring, Ernst Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck and August Thalheimer.

The First Decrees of the “Council of People’s Commissars”

On November 12th, the “Council of People’s Commissars” abolished martial law and censorship, together with wartime direction of labour, amnestied all political prisoners and provided for unemployment relief. On the other hand, it informed the High Command that it confirmed the officer corps, in its command of the armed forces and declared that the primary function of Soldiers’ Councils was the maintenance of military discipline.

On November 18th, the government set up a commission, headed by Kautsky, to examine which industries, were “ripe for nationalisation”.

The First National Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils

On December, 16th 1918, the First National Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils assembled in Berlin.

It met for five days and was attended by 489 delegates, of which 291 (60%) were members of the SPG, 90 (20 %) members of the ISPG, and only 10 (2%) Spartacists. Neither Karl Liebknecht nor Rosa Luxemburg was elected as a delegate.

The Organising Committee of the Congress had invited a Soviet delegation to attend, but this was turned-back at the frontier on the instructions of the “Council of People’s Commissars”.

Max Cohen-Reuss, on behalf of the SPG, warned the Congress not to attempt to replace “parliamentary democracy” by government through workers’ and soldiers’ councils, since this would “make civil war inevitable”. His resolution that the future of workers’ Councils lay purely in the economic not the political field, and that the councils should transfer their “power” to the “Council of People’s Commissars”, was carried by 400 votes to 50. The Congress went on to fix elections to the Constituent Assembly for, January 19th, 1919.

On the third day of the Congress, the chairman of the Hamburg Soldiers’ Council, an SPG member named Lamp’l, presented demands from the soldiers which came to be known as the

Lamp’l or Hamburg Points. They included demands that the highest authority in the armed forces should be the Council of People’s Commissars and not the High Command, that all badges of rank should be abolished, that soldiers’ councils should be responsible for military discipline, and that officers should be elected by the men.

A new Central Council of Workers and Soldiers’ Councils was set up succeed the Executive Council (which had been predominantly representative of Berlin). When it was decided

that the functions of this Central Council should be merely advisory, the ISPG contingent boycotted it, so that only the SPG was represented on it.

On December 20th, a High Command deputation to the “Council of People’s Commissars”, consisting of General Wilhelm Groener and Major Kurt von Schleicher, strongly objected to the Hamburg Points and was given assurances that they would not be put into effect.

By the end of the congress, it was clear that the aim of the of the German capitalists – to save capitalist society through the instrument of the Social-Democratic party of Germany — had been, at least for the time being succcessful.

The Shelling Of the Royal Palace

On the night of December 23rd./24th., 1918, sailors belonging to the People’s Naval Division, whose pay was in arrears, took prisoner Otto Wels (SPG), the commandant of Berlin, holding him as a hostage in the royal palace where they were quartered.

Ebert authorised the army to rescue Wels, and troops commanded by Lieutenant-General Arnold Lequis began to shell the palace. Later, however, the attacking troops mutinied and a truce was arranged; the sailors were given a safe conduct from the palace, together with their arrears of pay.

On the following day, Christmas Day, a crowd of 30,000 workers and soldiers, led by Spartacists, took part in a protest demonstration against the attack on the sailors, occupying the building of the principal SPG newspaper, “Vorwarts” [“Forwards], and forcing the staff to print a front-page article condemning the Ebert government.

Resignation of the ISPG Ministers

On December 29th., 1916, under the pressure of the rank-and-file of their party, the three ISPG Ministers resigned from the government in protest at the attack on the sailors, and were replaced by members of the SPG.

The Foundation of the Communist Party

On December 29th., 1918, a closed conference of the Spartacus League in Berlin resolved to secede from the Independent Social-Democratic Party and to found a new party.

From December 30th.; 1918 to January 1st., 1919, a joint conference of some 100 delegates from the Spartacus League, and the International Communists of Germany (Internationale Kommunisten Deutschlands) — a small socialist group in Bremen, known until November 1918 under the name Bremen Left Radicals [Linksradikalen Bremens] — was held in the hall of the Prussian Chammber of Deputies in Berlin. The conference resolved to transform itself into the First Congress of the Communist Party of Germany (Spartacus League) (CCG) [Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (Spartakusbund)] (KPD).

Karl Radek delivered an oration as a fraternal delegate from the Russian Communist Party, and the congress sent greetings to the Soviet Republic.

The Congress denounced the Ebert – government as “The mortal enemy of the proletariat”, and condemned the policy of the Second International, and called for the setting up of a new International.

Rosa Luxemburg introduced the Party programme, largely drafted by herself and previously published in “Red Flag” on December 14th, 1918, declaring:

“The immediate task of the proletariat is none other than to realise Socialism and to eradicate capitalism root and branch”.

(Bericht uber den Grundensparteitag der Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands (Spartakusbund); Berlin; 1919; p. 25).

The programme contained a number of Rosa Luxemburg’s anti-Marxist-Leninist views – belief in spontaneity, underestimating of the leading role of the Party, overestimation of the strike as a revolutionary weapon:

“The battle for socialism can only be carried on by the masses . . . Socialism cannot be made, and will not be made; to order . . . And what is the form of the struggle for socialism? It is the strike”.

(lbid; p.33) .

The most important part of the congress centred upon the question of whether the Party should participate in the forthcoming elections to the Constituent National Assembly. Against the opposition of Liebnicht and Luxemburg, the congress adopted by 62 votes to 23 a leftist resolution to boycott the elections.

As Lenin commented in April 1920:

“Contrary to the opinion of such prominent political leaders as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, the German “Lefts” considered parliamentarism to be ‘politically obsolete’ as far back as January 1919. It is well known that the ‘Lefts’ were mistaken”.

(V. I. Lenin: “Left-wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder”, in: “Selected Works”., Volume 10; London; 1946; p. 98).

Although no vote was taken on the question, a majority at the congress also agreed with the slogan put forward by a “leftist” faction headed by Otto Ruhle and Paul Frohlich: “Out of the trade unions!”

The congress elected a Central Bureau (Zentrale) as follows:

Hermann Duncker, Kate Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frohlich, Leo Jogiches, Paul Lange, Paul Levi, Karl Liebnicht, Rosa Luxemburg, Ernst Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, and August Thalheimer.

1919

The January Rising in Berlin

On January 3rd., 1919, the ISPG Ministers in the Prussian state government followed the example of their colleagues in the central government and resigned. This left only one member of the ISPG holding a key position Emil Eichhorn, chief of police in Berlin. Later on the same day, the Prussian Prussian Ministry of the Interior dismissed Eichhorn from his post,

On Sunday, January 5th., a huge protest demonstration against the dismissal of Eichhorn, organised jointly by the “Revolutionary Shop Stewards” and the Berlin leaderships of the ISPG and CPG, filled the streets of central Berlin. In the afternoon a section of the demonstrators occupied once more the offices of “Forward” which became until January 11 th, the organ of the revolutionary workers of Berlin.

That evening representatives of the newly-formed Communist Party, of the ISPG and of the “Revolutionary Shop Stewards” met and set up a Revolutionary Council (Revolutionsausschuss) of 33 members, which declared the Ebert government deposed and called for armed struggle to establish the political power of the working class:

“Comrades! Workers! The Ebert-Scheidemann government is declared deposed by the undersigned Revolutionary Council the representatives of the revolutionary socialist workers and soldiers . . .

The undersigned Revolutionary Council has taken over the function of government for the time being.

Comrades! Workers!

Join the action taken by the Revolutionary Council!

(Cited in: G. Lodebour (Ed.). “Der Ledebour Prozess”. Berlin; 1919; p. 55).

However the sailors declared their neutrality and the mass of the workers were not prepared to engage in armed struggle. Only a few hundred workers followed the revolutionary leaders to occupy a number of public buildings.

Meanwhile, on January 6th, the “Council of People’s Commissars met in hiding (the Chancellery being surrounded by a hostile crowd) and appointed SPG leader Gustav Noske to be commander-in-chief in Berlin, charged with the task of “restoring order”. He set up his headquarters in a school in Dahlem, a Berlin suburb, and began the organisation and training of a “Free Corps” (Freikcorps), composed mainly of reactionary officers and non-commissioned officers of the demobilising army.

On January 9th, Noske’s Free Corps began their attack upon the Berlin workers and the Central Bureau of the CPG, the Berlin leadership of the ISPG and the “Revolutionary Shop Stewards” issued a joint call for a general strike.

The governments first success against the revolutionaries was the recapture of the “Forward” offices on the night of January 10/11th, and on January 11th, Noske led 3,000 Free Corps into central Berlin where, after bloody fighting, the systematic reconquest of the city was completed by the evening of January 12th.

The Soviet Republic in Bremen

On January 10th., 1919, a great demonstration in Bremen, organised by the Communist Party demanded the transfer of political power to the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils, which proceeded to set up a Council of People’s Commissars composed of 3 representatives each from the CPG, the ISPG and the Soldiers’ Council and declared this to be the government of the Soviet Republic of Bremen.

On February 4th, on the orders of Noske, a large force of troops made an assault upon Bremen and had, by the evening overthrown the Soviet Republic.

The Murder of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg

On January 15th, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, who had refused to leave Berlin, were captured and brutally murdered by members of the Free Corps. Captured with the two leaders was another leading member of the CPG, Wilhelm Pieck, who later “escaped” under mysterious circumstances. One of the officers involved, Captain Pabst, stated later that he (i.e., Pieck Ed.):

“Was released because he had supplied information about other Spartakus personalities which facilitated their arrest”.

(J.P. Nettle: “Rosa Luxemburg”, Volume 2; London; 1966; p.780).

Pieck later emerged as a leading exponent of revisionism within the Communist Party of Germany.

The Soviet Republic of Bavaria

In one state, Bavaria – revolutionary resistance to the Scheidemann government continued until May 3rd, 1919.

In November 1918 the Workers’, Peasants’, and Soldiers’ Councils in Munich, under the leadership of the ISPG, had proclaimed a “Social and Democratic Republic of Bavaria”, and set up a government of ISPG and SPG Ministers, with Kurt Eisner (ISPG) as Prime Minister.

When elections were held to the State Parliament in January/February 1919, however, the ISPG received only 2.5% of the vote. On his way to the State Parliament to hand in his cabinet’s resignation on the February 21st, Eisner was murdered by a right-wing officer, Anton Graf von Arco auf VaIley. A new state government was then set up, headed by Johannes Hoffmann (SPG)

The CPG, ISPG, SPG and the Executive Council Of the Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Councils set up – following the murder of Eisner – an Action Council (Aktionsausschuss), which in turn set up a new Central Council of the Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Councils and called a three-day general strike throughout Bavaria. The Central Council, however, refused demands for the effective arming of the working class.

In these circumstances, on the evening of April 6th, 1919, on the initiative of the ISPG and against the opposition of the SPG, a “Council of People’s Commissars” (Rat der Volksbeauftragten) was established in Munich, headed by playwright Ernst Toller and phillosopher Gustav Landauer, (both ISPG).

On April 7th, the “Council of People’s Commissar’s” proclaimed a “Soviet Republic of Bavaria“. The Hoffmann government fled to Bamberg, in northern Bavaria, from where it prepared, with the support of the capitalist class and part of the peasantry the military overthrow of the “Soviet Republic”.

The CPG demanded that the “Council of People’s Commissars” should take urgent measures to meet the threat of armed intervention, but the “Soviet Government” refused to arm the workers or to make my serious inroads into the capitalist state machine.

On the night of April 12/13th, Free Corps forces, on the instructions of the Hoffmann government, invaded Bavaria, but were beaten back by the workers’ and soldiers of Munich.

The area and barracks Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Councils now declared the Central Council of their councils and the ”Council of People’s Commissars” deposed, and set up as legislative and executive organ of the Soviet Republic of Bavaria an Action Council of 15 members drawn from the CPG, the ISPG and the SPG. It elected an Executive Council of 4 members, which functioned as the Soviet Government, headed by Communists Eugen Levine and Max Levien.

On April 14th, the Soviet Government of Bavaria called a ten-day general strike and ordered the arming of the workers and their organisation into a Red Army. The Soviet Government also proceeded to disarm the reactionary forces, to replace the representatives of the capitalist class in the administrative by workers, to hand over control of production to the factory councils, and to nationalise the banks.

On April 27th, 1919, Lenin sent a massage of greetings to the Soviet Republic of Bavaria.

On April 30th., 1919, some 60 thousand Free Corps troops, commanded by Colonel Ritter von Epp, launched a second attack on Munich. The Red Army fought heroically for several days until, on the night of April 3rd/4th , the last units were destroyed in bitter fighting.

Martial law was proclaimed in Munich, and in the white terror, which followed, hundreds of revolutionary workers, soldiers and intellectuals were brutally murdered, and more than 12,000 thrown into prison.

The Foundation of the Nazi Party

On January 5th, 1919, the fascist “German Workers’ Party” (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) was founded in Munich on the initiative of Anton Drexler. It was joined in September 1919 by Adolf Hitler.

In March 1920 the party changed its name to the “National Socialist German Workers’ Party” (NSGWP) (Nationalsoczialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) (NSDAP) and came to be known as the “Nazi Party“.

The Elections to the National Assembly

The elections to the National Assembly took place on January 19th, 1919, under adult suffrage for both sexes and with proportional representation.

Most of the older political parties had changed their names in November 1918 to “people’s parties” in an effort to suggest that they had a progressive character. The German Conservative Party, the Free Conservative Party and the Christian-Social Party had merged to form the German National People’s Party (GNPP) (Deutschnationale Volkspartei) (DNVP), while the National Liberal Party had become the German People’s Party (GPP) (Deutsche Volkspartei) (DVP) – both of these parties at this time still representing the interests of the landed aristocracy. The Centre (a party representing the interests of the capitalists, but with its appeal directed principally towards Catholic electors) had become (temporarily) the Christian People’s Party (CPP) (Christliche Volkspartei) (CVP). The Social-Democratic Party of Germany and the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany (both representing the interests of the capitalists, but with their appeal directed toward principally toward class conscious working people) continued under their old names. In addition, a new party representing the interests of the capitalists but with its appeal directed principally towards “liberal” workers’ and petty bourgeois had been set up in November 1918 – the German Democratic Party (GDP) (Deutsche Demokratische Partei) (DDP). The only party representing the interests of the working class, the Communist Party of Germany, (CPG) boycotted the elections, as has been said.

The results of the elections to the National Assembly were as follows:

Party Votes (million) Per Cent Number of Deputies

Social-Democratic Party of Germany: 11.5 3 8% 165

Christian People’s Party: 6.0 20% 91

German Democratic Party: 5.6 19% 75

German National People’s Party: 3.1 10% 44

Independent Social-Democratic

Party of Germany: 2.3 8 % 22

German People’s Party: 1.3 4% 19

Other parties: 0.5 1% 7

Total: 30.3 million 423

The Election of Ebert as President

The new National Assembly met for the first time on February 6th, 1919, in Weimar. Weimar was selected for its cultural associations rather than Berlin which, as the centre of the Prussian state, symbolised Prussian aristocratic and military hegemony over Germany. Even more important, the Assembly was there able to obtain safer military protection from the militant workers and soldiers.

On February 11th, 1919, the National Assembly elected Friedrich Ebert (SPG) as first President of the Realm.

The Formation of the Scheidemann Government

The ISPG having refused to take part in a coalition government with the SPG, on February 13th, 1919, a new coalition government comprising Ministers drawn from the Social-Democratic Party of Germany, the Centre (formerly the Christian People’s Party) and the German Democratic Party – a coalition which formed the Parliamentary core of the Weimar Republic during its early years and became known as the “Weimar Coalition” – was formed with Philipp Scheidemann (SPG) as Chancellor.

The Formation of the Arm of the Realm (Reichswehr)

On February 27h, 1919, the National Assembly approved the law for the establishment of a “provisional army” the “Arm of the Realm” (Reichswehr). Its officers and non-commissioned officers were drawn mainly from the old imperial army, the rank-and-file principally from the reactionary Free Corps.

No provision was made in the law for Soldiers’ Councils, thus annulling the Hamburg Points.

The March General Strike in Berlin

On March 1st, 1919, the CPG issued a call for a political general strike to begin on March 3rd, directed against the counter-revolutionary policies of the Scheidemann government. The political demands put forward included the recognition of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils and the Hamburg Points; the abolition of courts martial; the freeing of political prisoners; the dissolution of the Free Corps, the formation of a workers’ defence force; and the establishment of trade and diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia. Most of these demands, and the strike call itself, were endorsed by the Executive Council of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils of Greater Berlin, and even the SPG leaders who had voted against the strike were compelled to join it.

The strike paralysed Berlin for five days. Then, on the pretext that the extension of the strike to gas, water and electricity might be harmful to public health, the SPG leaders resigned from the strike committee on March 8th.

Minister of the Arm of the Realm Gustav Noske immediately declared martial law, and ordered Free Corps troops to march into Berlin to smash the strike. Some thousands of workers and soldiers engaged in armed resistance to the Free Corps.

On March 10th, Leo Jogiches, a member of the Central Bureau of the CPG, was murdered by Free Corps officers, and on March 11th, 29 sailors belonging to the People’s Naval Division were shot.

After several days of severe fighting, in which more than 1,200 workers lost their lives, Berlin was occupied by Free Corps troops on March 12th.

The Foundation of the Communist International (Comintern) (C.I.)

The Communist (or Third) International (Comintern) (C.I.) was established at a conference in Moscow from March 2nd to 19th, 1919, attended by 35 voting delegates from 21 countries.

Of the two delegates elected by the Communist Party of Germany to attend the conference, only one, Hugo Eberlein, succeeded in reaching Moscow. He was mandated to oppose the setting up of the International ‘for the time being”. The leadership of the CPG felt that, with the weakness of the Communist movement as yet outside Soviet Russia a new International would in these circumstances be dominated by the Bolsheviks.

The mandate was originally due to Rosa Luxemburg, but was confirmed after her death by Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi, and Wilhelm Pieck. (“Kommunisticheskii internatsional”, No. 187-88; 1929; p.194).

According to Ernst Meyer at the Fifth Congress of the CPG in 1921, Eberlein had been instructed to walk out of the conference if the decision were taken to proceed with the founding of the new International. (Bericht uber den 5. Parteitag der Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands (Spartakusbund); n.p; 1921; p. 27).

Eberlein found himself, however, isolated at the conference, and on March 4th,. the conference voted without opposition (Eberlein had been persuaded to abstain from voting) to transform itself into the First Congress of the Communist International.

Among the more important documents approved by the Congress were “Theses on Bourgeois Democracy and Proletarian Dictatorship”, (drafted by Lenin), the “Platform of the Communist International”; an “Appeal to the Workers of all Countries”; “Theses on the International Situation and the Policy of the Entente”, and a “Manifesto to the Proletariat of the Entire world”.

The congress set up an Executive Committee to lead the work of the International, composed of members nominated by the Communist Parties of Soviet-Russia, Germany, German Austria, Hungary, the Balkan Federation, Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries. The ECCI was to have its seat in Moscow and was to elect a Bureau of five persons to carry on the day-to-day work of the International. In this connection, Grigori Zinoviev (Soviet Russia) was, after the congress, elected Chairman.

The ECCI reported to the Second Congress of the Communist International in July/August 1920 that only the Soviet Russian and Hungarian Parties had been able to send permanent delegates. (Der I Kongress der Kommunistischen Internationale: Protokoll der Verhandlungen in Moskau vom 2 bis zum 19 Marz 1919; Hamburg; 1921)

In May 1919 the Executive Committee began publication of the organ of the C.I., “The Communist International” ; in several languages.

The ISPG Declares for the Dictatorship of the Proletariat

From March 2nd, to 6th, 1919, an Extraordinary Congress of the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany was held in Berlin, attended by delegates representing 300 thousand workers.

A draft programme by Ernst Daumig was presented at the Congress and, although modified to some extent as a result of right-wing opposition led by Karl Kautsky, the programme finally adopted by the congress represented a considerable victory for the left-wing, since it came down firmly in favour of the dictatorship of the proletariat:

“The . . . party takes its stand on the council system. It supports the councils’ in the struggle for economic and political power. It strives for the dictatorship of the proletariat, the representative of the great majority of the nation, as the essential prerequisite for the realisation of socialism”.

(Unabhangige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands: Protokoll uber die Verhandlungen des ausserordentlichen Parteitages der USPD; Berlin; 1919; p. 3).

The Second National Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils

The second National Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils was held in Berlin from April 8th to 14th, 1919, attended by 142 delegates belonging to the SPG and 57 belonging to the ISPG. There were no delegates belonging to the Communist Party.

Dominated by the SPG, the congress resolved to turn over its “power” to the National Assembly.

The Treaty of Versailles

On May 7th, 1919, the terms of the Versailles Peace Treaty were conveyed by representatives of the Allied Powers to the German Foreign Minister, Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau.

The principal aims of the victorious imperialists in imposing the Treaty of Versailles upon defeated Germany were to make Germany militarily impotent, to annex parts of her territory and all her colonies, and to drain a large proportion of her economic wealth for many years to come for their benefit.

Part 1 of the treaty set up the League of Nations, an “international body” to be controlled by the European Allies and Japan (The United States government refused to join).

Parts 2 and 3 defined the portions of Germany proper to be detached from her territory. Moresnet, Eupen and Malmedy were to be ceded to Belgium; Alsace-Lorraine with its iron-fields to France; northern Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark; West Prussia and most of the province of Posnan to Poland (thus establishing a “Polish corridor” to the sea separating East Prussia from the rest of Germany). The Saar basin was placed under the control of the League of Nations, but with its coal mines under French control; a plebiscite was to be held among the population of the Saar after 15 years to determine its future. The left bank of the Rhine and part of the right were to be demilitarised.

Danzig was to be a “free city” under the sovereignty of the League of Nations.

Memel and southern Silesia were also detached from Germany; the former was ceded to Lithuania in 1924, the latter to Poland in 1921.

Part 4 deprived Germany of all her overseas colonies, which were placed under the nominal sovereignty of the League of Nations, which in turn transferred them to various of the Allied powers as “mandates”. In Africa, the Cameroons and Togoland were divided between France and Britain, while South-West Africa passed to the Union of South Africa. In the Pacific, the Marshall Islands went to Japan, New Guinea to Australia, West Samoa to New Zealand, Shantung to Japan (which ceded it to China in 1923), and Nauru was divided between Britain, Australia and New Zealand.

Part 5 laid down limits on the size of the German armed forces. The army was to be restricted to 100,000 men, and the formation of a General Staff was prohibited. The navy was restricted to 6 battleships, 16 light cruisers, 12 destroyers and 12 torpedo boats, with submarines prohibited; the remaining ships were taken by the Allies. No replacement ship was to exceed 10,000 tons, and naval personnel were limited to 15,000 men and 1,500 officers and warrant officers. Conscription for the armed forces was prohibited, together with any military or naval air force. Inter-Allied commissions of control were set up for each arm of the service to operate until 1925, after, which this was to be taken over by the League of Nations.

Part 7 charged some 100 Germans (including ex-Emperor Wilhelm II and Field Marshal von Hindenburg) with war crimes, but no significant action was taken under this section.

Part 8 laid down that Germany must pay reparations for “all damage done to the civilian population of the Allies by the aggression of Germany”. A Reparations Commission was set up to determine not later than May 1st, 1921, the sum to be paid. Meanwhile, Germany was to pay preliminary reparations of Pounds Sterling 1,000 million. The Allied countries were to receive “most favoured nation” treatment from Germany for five years without reciprocity, and France was to be exempted from customs duties for five years on the products of Alsace-Lorraine.

Part 12 established control of the rivers Rhine, Elbe and Oder by “international commissions”. The Kiel Canal was left under German control, but made to permit free access to all vessels of countries at peace with Germany.

Part 14 established Allied control of the Rhineland for 15 years. If Germany “faithfully carried out” the terms of the treaty, the Cologne zone was to be evacuated after 5 years, the Coblenz zone after 10 years, and the Mainz zone after 15 years. If, at any time the Reparations Commission decided that Germany was not fulfilling its obligations with regard to reparations, however, the whole or part of these areas could be reoccupied.

Foundation of the Association Of Communist Land Workers and Small Peasants

On May 17th, 1919, the Association Of Communist Land Workers and Small Peasants of Germany (Verband Kommunistischer Landarbeiter and Kleinbauern Deutschlands) was founded on the initiative of the CPG, and began to publish a weekly newspaper “The Plough” (Der Pflug).

The Retirement of Hindenburg and Groener

In 1919 Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Wilhelm Groener retired from active military service.

The Formation of the Bauer Government

There was at first disagreement among the German imperialists as to whether the Versailles Treaty terms should be accepted. In the cabinet 6 Ministers were for acceptance, 8 (in particular the representatives of the German Democratic Party) were for rejection.

On June 20th, as a result of these differences within the cabinet, the Scheidemann government resigned.

On June 21st, a new coalition government was formed, composed of representatives of the. Social-Democratic Party and the Centre (without the participation of the German Democratic Party) with Gustav Bauer (Centre) as Chancellor.

Acceptance of the Versailles Treaty

On June 28th., 1919, the German delegation to the Peace Conference signed the Versailles Treaty on the instructions of the new government.

On July 31st, the National Assembly approved acceptance of the treaty by 237 votes to 138 – against the opposition of the German national People’s Party, the German People’s Party and the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany.

The treaty came into effect on August 14th, 1919.

The Weimar Constitution

On July 31st, 1919, the National Assembly approved — against the opposition of the German National People’s Social Party, the German People’s Party and the Independent Democratic Party of Germany — the new Constitution, drafted in the main by Hugo Preusse, a lawyer member of the German Democratic Party.

This constitution, known as the “Weimar Constitution” reflected the changes brought about by the completion of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in November 1918. The remnants of formal political power remaining in the hands of the Prussian landed aristocracy were now abolished, and the capitalists became the sole ruling class of Germany under the façade of the “parliamentary democracy” of the Weimar Republic.

To emphasise the historical continuity with the former Empire, the new constitution continued the old name of “Realm” (Reich) rather than “Republic”, although the Realm was described in Article 1 as a republic in which political authority derived from “the people”.

Germany remained a federal state, but the powers of the central government were greatly increased, and the special rights of Prussia (in fact, of the Prussian landed aristocracy) were abolished.

The head of state was a President (Prasident), to be in future directly elected for a period of seven years. Special Emergency powers were granted to the President under Article 4b, by which he could “suspend the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution” and rule by decree when he considered that “public security and order” were endangered.

A bicameral legislature was established. The principal chamber in the parliamentary facade was the “Parliament of the Realm” (Reichstag), elected by direct ballot, but there was also a federal “Council of the Realm” (Reichsrat) ostensibly to give representation to the states but, in fact without effective powers.

The constitution incorporated factory councils into the state apparatus for the regulation of “industrial relations” .

The constitution came into force on August 14th, 1919.

The “Leftist” Opposition to ”Work in the Trade Unions

At a National Conference of the Communist Party of Germany, held in Frankfurt on August16/17 th, 1919, an attack was launched upon the policy of the Communist International, that Communists should work in mass trade unions under reformist leadership, by a “leftist” opposition headed by Heinrich Laufenberg and Fritz Wolffheim. They proposed that all Party members should withdraw from the trade unions and form a single comprehensive “left” trade union. (O.K.Flechtheim: “Die Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands in der Weimarer Republik”;

Offenbach; 1948; p. 59).

The ECCI Circular Letter On Parliament And the Soviets

On September 1st, 1919, the Executive Committee Of the Communist International issued a circular letter on parliament and the Soviets.

This stressed that the form of the proletarian dictatorship is Soviets, not parliament; nevertheless:

“We can help to abolish an organisation by entering it, by ‘exploiting’ it. . .

It is necessary:

1) that the centre of gravity of the struggle shall be outside parliament;

2) that the action inside parliament shall be bound up with this struggle;

3) that the deputies shall also do illegal work;

4) that they shall act on the instructions of the Central Committee and subordinate themselves to it;

5) that in their actions they shall disregard parliamentary forms. . . We cannot, on principle, renounce the utilisation of parliament”.

(Manifest, Richtlinien, Beschlusse des ersten Kongresses: Aufrufe und offene Schreiben des Exekutivkomitees bis zum zweiten Kongress; Hamburg; 1920; p. 139).

It declared that, since parliamentary activities are auxiliary activities, differences on the question of participation in parliamentary activities should not be made the pretext for splitting a Communist party:

“Parliamentary activities and participation, in the electoral campaigns are only auxiliary activities, nothing more.

If that is so, and it undoubtedly is, then it is obvious that it is not worth while splitting over differences of opinion on this subsidiary question. . .

Therefore we appeal urgently to all groups and organisations who are genuinely fighting for Soviets to proceed with the utmost unity even if on this question they are not of one mind. All who are for Soviets and the proletarian dictatorship will unite as quickly as possible and form a unified Communist Party”. (Ibid; p.139).

Lenin’s “Greetings to Italian, French and German Workers”

On October 10th, 1919, Lenin sent a message of greetings to Italian, French and German Communists in which he declared that the differences among the German Communists related to the questions of participating in parliamentary activities and of working in mass trade unions under reformist leadership.

“The differences among the German Communists boil down. . . to the question of ‘utilising the legal possibilities’ . . .of utilising the bourgeois parliaments, the reactionary trade unions, the factory councils law’”.

(V. I. Lenin: “Greetings to Italian, French and German Communists”, in: “Against Revisionism”; Moscow; 1959; p.521)

He declared that those who advocated the boycotting of these bodies on principle were undoubtedly mistaken:

“Both from the standpoint of Marxist theory and the experience of three revolutions . . I regard refusal to participate in a bourgeois parliament, in a reactionary . . . trade union, in the ultra-reactionary workers’ ‘councils’ as an undoubted . . . mistake.

A mistake remains a mistake, and it is necessary to criticise it and, fight for its rectification”. (V.I. Lenin: Ibid; p.522, 52).

and that the source of this error was lack of revolutionary experience:

“This error has its source in the lack of revolutionary experience among utterly sincere, convinced and valiant working-class revolutionaries.”

(V.I.Lenin: Ibid.; p. 525).

The differences on these questions were, Lenin emphasised, subsidiary in character:

“These are differences between representatives of a mass movement that has grown up with incredible rapidity, differences that have a single, common, granite-like, fundamental basis: recognition of the struggle against bourgeois-democratic illusions and bourgeois democratic parliamentarism, recognition of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and Soviet government”. (V.I. Lenin: Ibid.; p.519).

which will disappear with the growth of the Communist movement:

“This is a matter of growing pains; it will pass with the growth of the movement which is developing in fine style.”

(V.I. Lenin. ibid.; p. 522).

The West European Bureau and the “West European Secretariat”

In October 1919 the Dutch Communist S. Ruttgers was charged by the Communist International with the formation of a West European Bureau of the International in Amsterdam. This came into being in the first weeks of 1920, with D. Wijnkoop as President, and Ruttgers and Henriette Roland-Holst as Secretaries. It issued a bulletin in three languages.

About the same time (the autumn of 1919) a “West European Secretariat” was set up unofficially by the leadership of the Communist Party of Germany with headquarters in Berlin, as a counter-move to the formation of the Amsterdam Bureau.

Its heads were the Bavarian Communist Thomas, and M. Bronsky. At the Second Congress of the C.I. in July 1920, it was described as:

“… limited, narrow and to a certain extent nationalist and not international”.

(Der Zweite Kongress der Kommunist Internationale; Hamburg; 1921; p.590).

The Second Congress of the CPG

The Second Congress of the Communist Party of Germany was held illegally in the Heidelberg district from October 20th to 23rd, 1919, attended by 46 delegates representing 16,000 members.

The ebb of the revolutionary tide had led to a more realistic appraisal of the process of the socialist revolution in Western Europe as a protracted process embracing several stages, and made up of advances and setbacks. This view was reflected in the “Theses on Communist Principles and ‘Tactics” adopted by the Congress:

“The revolution, which consists not of a single line but of the long stubborn struggle of a class downtrodden for thousands of years and therefore naturally not yet fully conscious of its task and of its strength, is exposed to a process of rise and fall, of flow and ebb”.

(Bericht uber den 2. Parteitag der Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands (Spartakusbund); n.p.; n.d.; p.62).

The congress also considered “Theses on the Trade Union Question”, drafted by Paul Levi, which not only made it obligatory for ‘Communists to work in the reformist trade unions, but debarred from further participation in the congress those who ‘Voted against the theses.

(Ibid; p. 46).

After a bitter debate, the theses were carried by 31 votes to 18, and the minority were then excluded from the congress, (Ibid.; p. 42).

The expelled minority immediately began preparations for the formation of a new party (which came into being in April 1920) and succeeded in drawing away from the CPG nearly half its total membership, including the majority of its members in Berlin and North Germany.

Lenin disagreed strongly with the expulsion of the minority. On October 28th, 1919, he wrote to the Central Bureau of the CPG:

“The only thing that seems incredible is this radio report that . . . you expelled the minority which, they tell us, then set up a party of its own. Given agreement on this basic issue (for Soviet rule, against parliamentarism) unity, in my opinion, is possible and necessary. . . Restoration of unity in the Communist Party of Germany is both possible and necessary from the international standpoint.”

(V.I. Lenin: Letter to the CB of the CPG regarding the Split.. in: “Collected Works”, Volume 30; Moscow; 1965; p. 87-88).

The congress elected a Central Bureau as follows: Heinrich Brandler, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Levi, Ernst Meyer, Wilhelm, Pieck, August Thalheimer and Clara Zetkin.

The Foundation of the Communist Youth International

The Foundation Congress of the Communist Youth International (CYL) was held illegally in Berlin from November r 20th, to 26th, 1919, attended by 25 delegates from 14 youth organisations with a total membership of 200 thousand.

The Congress declared the organisation a section of the Communist International and adopted a “Manifesto to Working Youth” and “Statutes of the Communist Youth International”. It elected an Executive Committee of five members including Leopold Flieg and Wilhelm Munzenberg from the CPG.

The December Congress of the ISPG

From November 30th, to December 6th, 1919, an Extraordinary Congress of the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany was held In Leipzig.

A resolution that the Party should withdraw from the Second International was carried by 170 votes to 111, and a resolution to enter into negotiations with parties inside and outside the Communist International with a view to forming “an effective International” was carried by 227 votes to 54. (“Kommunisticheskii Internatsional”, No. 7-8; November-December, 1919; Col. 1113).

Following the congress, the Central Council of the ISPG wrote to the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party along these lines, but received no reply.

1920

The Separation of the Bavarian People’s Party

The Bavarian People’s Party (BPP) (Bayrische Volkspartei) (BVP) had been formed on November 12, 1918, as a working group within the Centre. It represented the interests of the landed aristocracy in Bavaria, and its appeal was directed particularly towards Catholic voters in that state.

On January 9th., 1920, the Bavarian People’s Party broke away from the Centre to form an independent political party.

The Demonstration against the Factory Councils Bill

In January 1920 the government introduced into the National Assembly the Factory Councils Bill, designed to transform factory councils into mere negotiating bodies.

The CPG and the ISPG called on workers to stage a mass protest demonstration against the Bill on January 13, in front of the Parliament Building. During the demonstration, troops guarding the building fired machine-guns into the demonstrators killing 42 and wounding 10.

The government immediately declared martial law (abolished only in December 1920) and under cover of this the Free Corps bloodily suppressed protest all over the country and

occupied the offices of the CPG and ISPG newspapers, while several hundred leading members of the two parties were arrested.

The ECCI Letters of February

On February 5th, 1920, the Executive Committee of the Communist International issued a general appeal:

“to all German workers, to the Central Bureau of the Communist Party of Germany and to the presidium of the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany”,

in which after drawing attention to past mistakes on the part of the ISPG, it invited this party to send delegates to Moscow for negotiations. At the same time, it rejected in advance all collaboration with the:

“Right-wing leaders. . . who are dragging back the movement into the bourgeois swamp of the yellow Second International”.

(“Kommunisticheskii Internatsional”, March 22nd, 1920; cols. 1381-92).

Two days later the ECCI sent a letter to the Central Committee of the newly-formed “leftist” Communist Workers’ Party of Germany, formed by the split in the CPG following its Second Congress, expressing disapproval of the party’s opposition to working in the mass trade unions and to participating in parliamentary elections, but inviting it to send delegates to Moscow for oral discussions. (Bericht uber den 3. Parteitag der Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands (Spartakusbund); n.p.; n.d.; p. 14).

The Third Congress of the CPG

The Third Congress of the Communist Party of Germany was held illegally in Karlsruhe on February 25/26th, 1920, attended by 43 voting delegates.

Clara Zetkin delivered a report on the international situations and on the work of the “West European Secretariat”. She claimed, that it had now developed “beyond its functions of information”, and had become “a central point of communication and union for Communists in Western Europe” (Ibid; p. 77).

Following her reports, strong criticism was expressed concerning the dealings of the ECCI with the “leftist” Communist Workers’ Party of Germany, and a resolution was passed calling for the retention of the “West European Secretariat” and for a World Congress of the CI in the near future to discuss the issues, between the ECCI and the CPG. (Ibid, p.84-85).

The congress expelled from the Party five entire districts: Greater Berlin, North, North-West, Lower Saxony and Dresden — for supporting the stand of their delegates on the trade union issue at the Second Party Congress in October 1919.

A Central Bureau was elected as follows: Heinrich Brander, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frobhlich, Ernst Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, August Thalheimer and Clara Zetkin. After the congress Paul Levi was coopted to the Central-Bureau.

The Kapp Putsch

At the beginning of March, 1920, the government, in pursuance of demands issued by the Inter-Allied Military Control Commission, ordered the disbandment of two brigades of marines stationed near Berlin under the Command of Captain Hermann Ehrhardt.

General Walter Freiherr von Luttwitz refused to comply with the order, and the government formally removed the brigades from his command.

On the night of March 12/13th, 5,000 members of the two brigades, led by Ehrhardt, marched into the centre of Berlin.

The government immediately sought the use of troops to crush the putsch, but General Hans von Seeckt, Chief of the Office of Troops at the Ministry of the Arm of the Realm,, replied:

“Obviously there can be no talk of letting Reichswehr fight against Reichswehr”.

The brigades occupied without opposition all the principal government buildings in the centre of Berlin. The leaders of the putsch declared the government desposed, the Weimar Constitution null and void and the National Assembly dissolved; they proclaimed a new government headed by Wolfgang Kapp, an East Prussian landowner. The Ministers of the legal government fled to Stuttgart, but before leaving issued a call for a general strike.

The leadership of the Communist Party at first adopted a “leftist” line towards the putsch, advising workers not to participate in the strike. On March 14th. “The Red Flag” declared:

“The revolutionary proletariat will not lift a finger to save the murderers of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg from disgraceful defeat. We shall not lift a finger for the democratic republic”.

The workers, however, responded to the strike call, which was endorsed by the trade union leaders belonging to the SPG, headed by Carl Legien (chairman of the largest trade union, federation, the General German Trade Union League) and 12 million workers, including the lower grades of the civil service, ceased work. In these circumstances on March 15th, the leadership of the CPG changed its line and advised support of the strike, but under the “leftist” slogan of “For a Soviet Government!”

In the Ruhr, under the leadership of the CPG, a Red Army of 100,000 men came into being and fought the counter-revolutionary troops.

In Berlin the strike was almost 100% effective and, after a few days in which Berlin was completely paralysed, on March 17th, the leaders of the putsch fled. The putsch had been defeated.

The right wing of the ISPG leadership now demanded a new government headed by Legien as Chancellor and including a majority of ISPG Ministers.

On March 21st, 1920, the Central Bureau of the CPG declared that, in the event of such a “workers’ government” being formed., they would adopt an attitude of “loyal opposition” towards it, i.e, they would refrain from attempting to overthrow it by force. (“Die Rote Fahne”, March 26th, 1920).

Lenin declared that these tactics were correct in principle:

“The conclusion: the promise to be a ‘loyal opposition’ (i.e., the renunciation of preparations for a ‘violent overthrow’) to a ‘Socialist government if it excludes bourgeois-capitalist parties’. Undoubtedly these tactics in the main, are correct”.

(V.I., Lenin: “‘Left-wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder”, Appendix 2, in: “Selected Works”, Volume 10; London; 1946; p.150).

However, he strongly criticised the formulation of the statement:

“We cannot (in an official statement of the Communist Party) describe a government of social-traitors as a ‘Socialist’ government. It is impermissible to speak of the exclusion of bourgeois-capitalist parties when the parties of both Scheidemann and Messrs. Kautsky and Crispien are petty-bourgeois democratic parties”.

(V.I. Lenin: ibid.; p. 150).

And declared that the reasons given for these tactics were:

“Wrong in principle and politically harmful”.

He suggested that a more correct formulation of these reasons would have been:

“As long as the majority of the urban workers follow the Independents, we Communists must place no obstacles in the way of these workers overcoming their past philistine-democratic (consequently also ‘bourgeois-capitalist’ illusions, by going through the experience of having ‘their own government’. This . . . means that for a certain period all attempts at a violent overthrow of a government which enjoys the confidence of a majority of the urban workers must be abandoned”.

V.I.Lenin, Ibid; p. 151).

In an “Open Letter” to members of the “leftist”‘ Communist Workers’ Party of Germany dated June 2nd., 1920; the ECCI confirmed Lenin’s objections to the statement of the CPG:

“The ECCI is completely out of agreement with the reasons given by the Spartacus League Central Bureau in its well-known statement of 21 March 1920 about the possibility of forming a so-called ‘purely socialist’ government. It was incorrect to state that such a ‘purely socialist’ government will ensure a situation in which ‘bourgeois democracy need not appear as capitalist dictatorship’”.

(Cited in: Manifest, Richtlinien, Beschlusse des Ersten Kongresses: Aufrufe und offene Schreiben des Execkutiv-komitees bis zum zweiten Kongress; Hamburg; 1920; p. 292)